The Free Press

Back when Donald Trump was last running for election, as the Great Awokening made its speech-chilling sweep through the American media, a small number of writers and public intellectuals admitted to not being entirely onboard with the new orthodoxy of privilege checking, sensitivity reading, racial affinity groups for 8-year-olds, and so on. These people were, depending on who you ask, either very brave or very stupid.

In public, and especially on Twitter, this cohort became objects of loathing and derision, excoriated by peers for refusing to “read the room.” But behind the scenes, we were inducted into a weird little priesthood of the unorthodox—mostly via Twitter DMs, which served as a sort of backchannel confessional for fellow writers who agreed that things appeared to be going off the rails, but were too afraid of being canceled to admit as much on main.

The first time I received one of these messages, it was from a woman named Jane. She was a colleague—we both had permanent freelance gigs at the same online teen magazine—and wanted me to know that she shared my concerns about the increasing hostility to free expression in progressive spaces.

“I’m trying to tell myself every day that this censorship, hypersensitivity etc is the natural exuberance of a new movement still feeling out its own limitations,” she wrote to me once, early on. “I spend so much time every day now wondering if my peers *actually* want to suspend the 1st amendment or are just angry/emotional/posturing.”

Jane would pop into my DMs every time a new censorship controversy erupted in our little corner of the internet, which is to say, we chatted frequently. When I wrote my first investigative feature about how the world of young adult fiction had been overtaken by campaigns to shame and censor authors in the name of diversity, she sent me effusive praise; when she worried aloud about her career, I offered advice and sent her leads on paid writing opportunities. When she wanted to vent about cancel culture, she always started by apologizing. She hated to burden me, she said; she just didn’t have anyone else to talk to.

Five years later, I had just published an article about the Covid-era campaign to eject Joe Rogan from Spotify when my friend Zac sent me one of those messages that almost invariably means someone is talking shit about you online: “Sorry,” he wrote, “but I thought you should probably know about this.” When I clicked on the link he’d sent, I discovered that I was being mocked via screenshot by a prominent podcaster who has always hated me for unknown reasons; what Zac wanted me to see was one of the first replies.

“I used to work with this person,” it read. “She was not always like this, but this particular strain of contrarianism is like heroin—there are very few casual users.”

The writer of this comment was Jane.

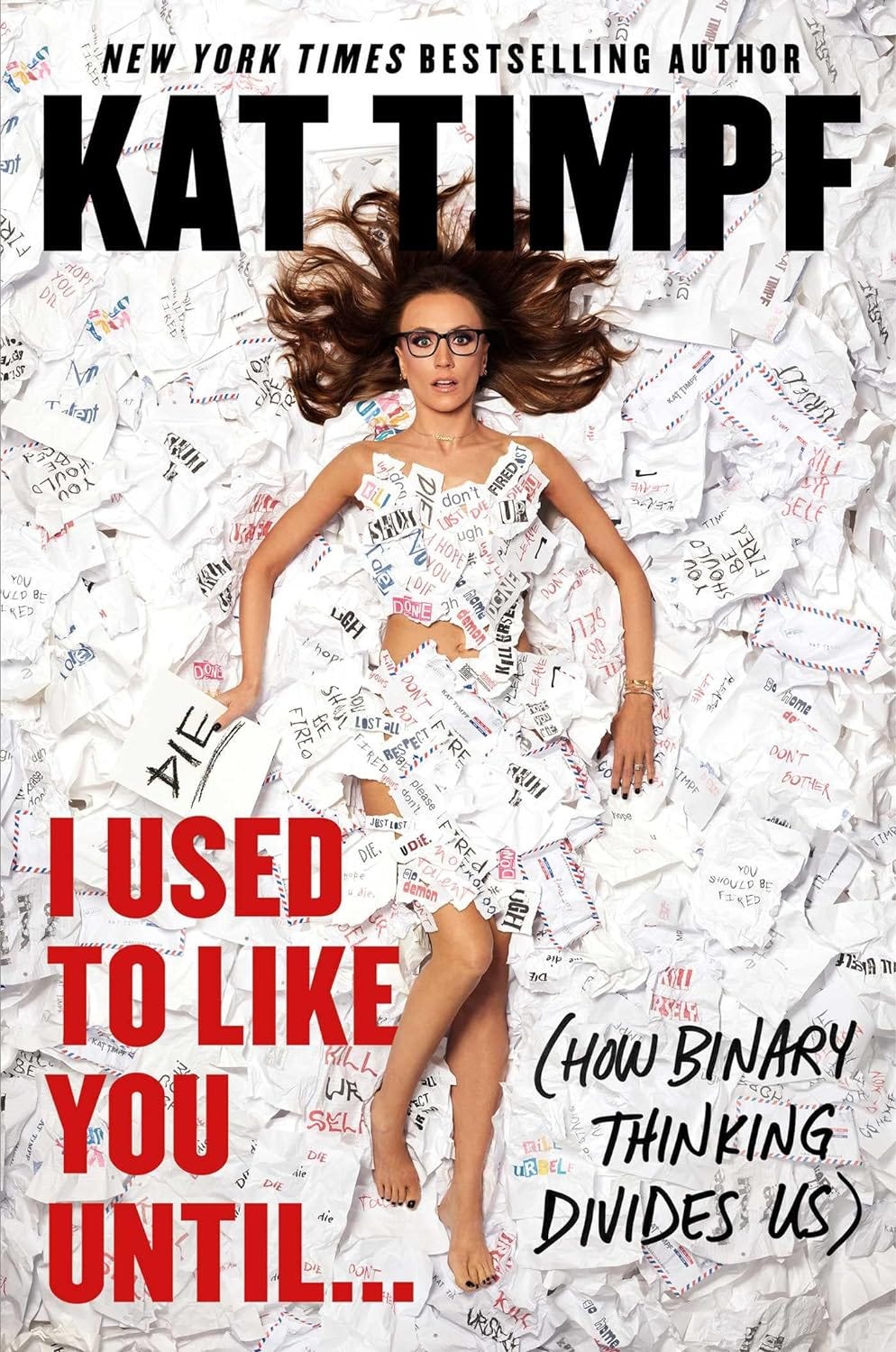

I thought of this incident recently while reading Kat Timpf’s book, which came out last week, I Used to Like You Until. . . A reflection on, per the subtitle, How Binary Thinking Divides Us, the book’s opening chapters are dedicated to describing the social liabilities of being employed at Fox News, where Timpf is a regular panelist on the late-night talk show Gutfeld! Her politics are more libertarian (small L) than conservative, and her brand of commentary more Phyllis Diller than Bill O’Reilly (she also does stand-up comedy), which makes her a bit of a misfit—if not on Fox News itself, then certainly in the minds of people who equate the network with a particular brand of shouty, Trumpy Republicanism.

This, Timpf describes with equal parts candid vulnerability and trademark self-deprecating humor: People who embrace her as a friend (or more) in private balk at acknowledging their relationship publicly. Strangers harass her by way of proving to whomever is nearby that they’re One of the Good Ones. In one especially colorful incident, Timpf’s budding romance with another woman comes to an abrupt end when her paramour’s mother, a gender studies professor, shows up and perp-walks her daughter out of Timpf’s house. Here is a living, breathing data point from those viral polls of Democratic parents who would rather their kids be gay than marry a Republican.

But Timpf’s broader thesis—and mine, as well—is not that the wokes are out of control. It’s that everyone is. A culture that arguably began in the crucible of progressive spaces has metastasized; today, there is no corner of the political landscape that has not devolved into a Manichaean clown show, all weaponized gossip and vacuous partisanship and recreational demonization of the outgroup.

Consider the moment in 2023 when Bud Light accidentally stepped on a landmine in the culture wars, after the company sent a commemorative can to TikTok influencer Dylan Mulvaney to mark the anniversary of her “Days of Girlhood” series, which documented her transition. The backlash to the stunt from the political right caused a catastrophic decline in sales from which the brand may never recover. But more importantly, Timpf notes, “all cans of Bud Light everywhere became politically charged, no matter who was drinking one or why”—no doubt to the bewilderment of the vast majority of Bud Light drinkers, for whom the name Dylan Mulvaney would have elicited nothing more than a furrowed brow and a “Dylan who?”

The contemporary practice of assigning a political gloss to everything, from TV shows to clothes to dairy products, reminds me of nothing so much as being 12 years old and trying to make sense of the constantly evolving and inscrutable standards that sorted the cool girls in my eighth-grade class from the losers. The binarism smacks of adolescence, when a fuzzy concept of self can only be coped with by slapping labels on everyone and everything else. Goth or preppy, hot or not, cool kid or pariah: I know you are, but what am I? High school, too, was a world in which the most arbitrary things became imbued with profound significance—your brand of sneakers, the cut of your jeans, the way you carried your backpack. God help the girl who was foolish enough to put both straps over her shoulders.

Also, crucially, it was a world in which there was no option to opt-out, no room for noncombatants. You may not have cared if your sneakers were Kmart knockoffs instead of actual Pumas, but other people would, and would label you accordingly—just as today’s discourse refuses to allow for the possibility that someone might drink a Bud Light not for any ideological reason, but just because he’s thirsty and has terrible taste in beer. You will be recruited into the culture wars. You will select a team and wear their colors and cheer, or jeer, accordingly. And you will engage in ritualized acts of performative contempt for your adversaries; indeed, this is the only way we can know for sure that you’re one of us, and not one of them.

This is where the comparison to high school ends, because high school itself ends, thank God, as do the bizarre and arbitrary social hierarchies that dominate it. The expectation, come age 18, is that you will put these childish notions aside and be grateful that you did. One of the great pleasures of adulthood is that you can eat, and wear, and watch what you like without worrying that nobody will sit with you at lunch because of it. Another great pleasure is laughing at the idea that any of these things ever mattered to anyone. There’s nothing like growing up to make you realize, to your immense relief, just how big the world is and what multitudes the people in it contain—yourself included.

Binary thinking robs us of those pleasures, and then extorts us for good measure: Give us your integrity, it says, and we’ll reward you with belonging. The viciousness with which these communities punish wrongthink and eject apostates does imply a more positive flip side, that if you say the right things, and hate the right people, the in-group will have your back. If associating with a problematic person could destroy your career, then surely publicly denouncing that same person should accrue some benefits.

I imagine this is what Jane was thinking, more or less, when she wrote what she did: that whatever value I offered as a friend and confidant, it was worth far less than the advantages she would gain by denouncing me in public. Then, as now, I was less angry at her than at the phenomenon she represented, of otherwise intelligent people somehow convincing themselves that trashing your former colleagues on Twitter is a recipe for success, as opposed to a giant, flashing neon sign advertising your lack of professionalism.

For this reason, I’ve given Jane a pseudonym—partly because I don’t want this article to damage her reputation, but more because I sincerely do not want to live in a society in which you can only trust a person up until the moment when it becomes more useful to throw them under the bus for internet clout.

I also suspect that most of the people who do this don’t really want it either, but are trapped in the paradigm that Timpf describes in her conclusion, inspired by a quote from John Updike: “Immersed in hate, he doesn’t have to do anything; he can be paralyzed, and the rigidity of hatred makes a kind of shelter for him.” Crucially, the shelter being described here isn’t made of a person’s own hatred; it is a hateful caricature of him made by others, one that offers protection in the sense that he can hide inside it and feel like the ultimate victim, maligned and misunderstood. There’s a peculiar comfort in that—the same one we’re seeking when we embrace as a political identity something that started out as an insult lobbed by the other side. Childless cat ladies! Nasty women! Deplorables!

Timpf’s point, persuasively made, is that politicians like it this way. When they use their platforms to fuel the culture wars rather than to create policy, spinning horror stories about the immigrants who will eat your cat, the gays who will trans your children, the Karen who will microaggress you to death if a racist cop or predatory dudebro doesn’t get you first, this isn’t just a distraction. It’s a tool of mass disenfranchisement, keeping us focused on the ideological bogeyman next door instead of the elected officials running the show.

“It’s pathetic, but it’s true: Politics makes us fight with the people we actually know on behalf of people who don’t even know we exist,” Timpf writes.

But the tragedy of our descent into tribalism isn’t just that it makes us into useful idiots for powerful, terrible people of all political persuasions. It’s that it traps us in a stunted place, a perpetual adolescence in which we substitute having the right politics for having a personality, in which we can’t even articulate who we are without an enemy to define ourselves against. If hate is a shelter, it’s also a cage—an intellectual and ideological Hotel California that offers protection from the elements but also keeps us from growing, or going, anywhere. You can check out anytime you like, but you can never leave.

Kat Rosenfield is a columnist at The Free Press. Read her piece “Teenage Girls Need Judy Blume More Than Ever” and follow her on X @katrosenfield.

Not everything is capable of compromise. At some point we have to respond appropriately and comments like Theresa Ghee's that "Revenge is not always a bad thing" are reasonable in some situations. BTW previously I was referring to the alliance with RFKJr. Yes, there is still family...and useful idiots...but do you really think RFK's family will remain the same after how he was treated? Of course we don't know how it was anyway. We can't forget that sometimes these things have real consequences that impact us personally. And maybe instead of turning the other cheek or remaining silent, we should re-evaluate our response or our perspective and speak up.

THE answer to the question is lack of courage, fear, income, desire to be accepted by the "group." It is often said that a person's character is determined by the tough times not the good times. So one ultimately must be true to oneself...except when? However what isn't discussed is the actual nature of this election as demonstrated by what has happened to date. This discussion should be about what is to come....and how much worse it will be. Anyone who believes things will improve is delusional. Biden followed in Obama's footsteps on Israel. Already censorship is discussed incessantly, most recently in California. There will be no need to be publicly shamed or supported when you won't be published at all. That is the real danger. Look at Newsom's later gambit on free speech. Don't doubt it. Censorship will impact TheFP too. And none of these discussions will occur.