Shortly after moving into his new Kansas City, Missouri, neighborhood in 2007 with his wife and four children, journalist David Von Drehle went out to fetch the newspaper and saw across the street a spritely older gentleman, bare-chested in the summer heat, washing a car. The car, it turned out, belonged to the man’s girlfriend.

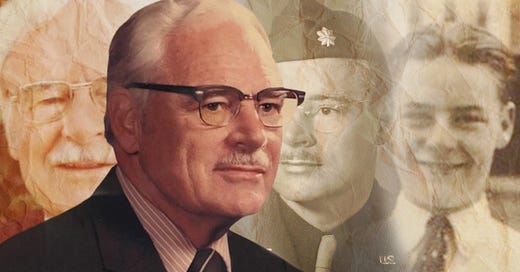

This would all be unremarkable except for the fact that the older gentleman, retired physician Charles White, was 102 at the time. As Von Drehle writes, “Charlie, I soon learned, was an extraordinary specimen: hale and sturdy, eyes clear, hearing good, mind sharp. His conversation danced easily from topic to topic, from past to present to future and back. Even so, one does not expect, on meeting a man of 102, to be starting—as we did that day—a long and rich friendship.”

But they did. Below is an excerpt from David’s new best-selling book, The Book of Charlie: Wisdom from the Remarkable Life of a 109-Year-Old Man, about his friend—and a now-vanished America. On Labor Day, it’s a great reminder of the importance of work and the capacity we all have to surmount any challenges that stand in our way.

Charlie White was born August 16, 1905, in Galesburg, Illinois, and died August 17, 2014, in Kansas City. He was among the last living Americans from the presidency of William Howard Taft (Barack Obama was president when Charlie died). He was among the last surviving officers of World War II, among the last physicians who knew what it was to practice medicine before penicillin, among the last Americans who could say what it was like to drive an automobile before highways existed, among the last people who felt amazement when pictures moved on a screen and sound emerged from a box. By the time Charlie was done, he had lived nearly half the history of the United States.

Still, as I’ve reflected on this remarkable friend, I’ve come to see that he was more than a living history lesson, and more than just the winner of a genetic Powerball. He was a case study in how to thrive through any span of years, short or long.

People often asked him the secret of longevity, and Charlie was always scrupulously honest: there’s no secret, just luck. But if he knew no secrets to a long life, he knew plenty about a happy life. Through tragedy and loss, poverty and setbacks, missteps and blown chances, he maintained a steadiness, an evenness, and a self-reliance that today might be called resilience. He had a gift for seizing joy, grabbing opportunities, and holding on to things that matter. And he had an unusual knack for an even more difficult task: letting go of all the rest.

One day in 1914, when Charlie was eight years old, his life was forever changed. His father, a 42-year-old minister and insurance salesman also named Charles, got into an elevator—one of the early electric passenger cars—in his office building. An inexperienced operator was at the controls, and as Charlie’s father entered the car, the operator put it in motion. Charles was crushed, and his body dropped down the shaft.