The Free Press

Until last week, I had been seriously considering teaching at Columbia University next year as a visiting professor. But I’m now convinced that to do so would be folly—to serve as a prop or a fig leaf. Moreover, I feel doing so would mean putting myself and my students at risk.

I have spent most of my professional career on American campuses, teaching courses on religion and history. I took a brief break to serve in the Biden administration as the United States’ Special Envoy to Monitor and Combat Antisemitism from May 2022 to January 2025.

It was from that perch that I watched the alarming unraveling of campuses that claimed to be dedicated to the pursuit of truth transform themselves into places where basic morality had been inverted. Following Hamas’s attack of October 7, 2023, things went from bad to worse.

These outrages began while I was working as a diplomat and State Department employee, and I was enjoined from involving myself in domestic matters. But I watched—often with horror—as university administrations coddled anti-Israel protesters who broke university regulations, harassed other students, and prevented the normal learning process from proceeding.

President Biden did condemn the violence, often unequivocally. “Destroying property is not a peaceful protest. It is against the law. Vandalism, trespassing, breaking windows, shutting down campuses, forcing the cancellation of classes and graduations, none of this is a peaceful protest.” But there were too many moments that were met with silence.

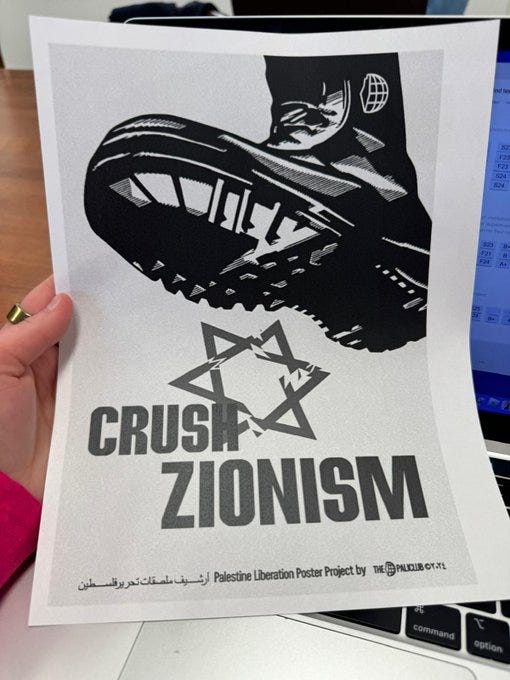

So I was pleased and surprised last week when Barnard, the women’s college of Columbia University, expelled two students who had participated in an assault on a Columbia course on the history of modern Israel in January of this year, on the first day of classes. The students marched into the room, disrupted the session, prevented it from proceeding, and distributed antisemitic flyers. One of the flyers read “Crush Zionism,” and had an illustration of a boot stomping on a Star of David. Another depicted an Israeli flag on fire and bore the caption “Burn Zionism to the ground.”

The class’s professor, Avi Shilon, modeling true academic inquiry, invited them to join the class and the conversation. But rather than engage, they preferred to disrupt, doing so with undisguised glee and self-righteousness. (Watch for yourself.)

But as Barnard took action, I wondered if the college would stand by its decision.

I had good reason to wonder. Over the past two years, universities have been overwhelmingly weak in their response to those clearly breaking university rules and even the law. When they have meted out punishments, often they have wound up walking them back, turning their responses into a farce.

Consider what happened at MIT in November 2023 when MIT student protesters, ignoring specific university instructions, conducted a demonstration that the university described as “disruptive, loud, and sustained” and which was “conducted in defiance” of previously issued warnings. The protest prevented research and learning. MIT “partially suspended” the students.

“Partial” meant they could not attend nonacademic events. In other words, they remained enrolled at the school.

In explaining this “partial” action, MIT’s president said it had not fully suspended them because it had “serious concerns about collateral consequences for the students, such as visa issues.” In other words, the protesters were foreign students and might be thrown out of the United States if they lost their student visas.

I, along with many others, thought that is exactly what should have happened. In fact, why should any student have that right?

Last year at Columbia we witnessed the same weakness when anti-Israel protesters forcibly took over Hamilton Hall, trapped custodians in the building, built encampments in violation of the university’s rules—and upended school life as it existed before October 7, all with little to no consequence both from the institution and ultimately from the city of New York, which dropped all charges.

Given all this, you can understand why I wondered about Barnard’s willingness to stick the landing. I was right to. Less than 24 hours after the university’s expulsion of two rule-breakers—two students who had disrupted Avi Shilon’s class—I had my answer.

On February 26, a group of protesters—it’s unclear how many were Barnard students—outraged by the expulsions, took over Milbank Hall, which houses both the dean’s office and classrooms, and demanded the reversal of the expulsion and amnesty for all those involved in the protest. They entered the building—masked and screaming—with such ferocity that an employee who confronted them was physically abused and had to be taken to the hospital. Students trying to go to class were locked out by university officials.

The same administration that had expelled two students a few days earlier engaged in multi-hour, drawn-out negotiations. The dean offered to meet with three representatives of the group—the group insisted on four—but stipulated that they come unmasked and provide identification to prove that they are indeed Barnard students. The students refused. The dean asked for permission to use the bathroom, which the student protesters were blocking. After some discussion, the students agreed. She was greeted with a chorus of boos as she made her way to and from the facility.

Classes that were to be held in that building were canceled. Consequences? None.

And so, the negotiations dragged on, effectively putting the university administrator and the protesters on equal ground. Faculty members who were present insisted that they were neutral and only wanted to prevent an escalation. Farcical. The students had already escalated the situation by their takeover and assault.

Finally, after some six hours, the students were told by the dean’s office that “we will not pursue disciplinary action for your presence in the building” if they left by 10:30 p.m.

They left. Consequences? None.

There have been too many humiliating dramas like these to count over the past year and a half. But I watched this saga with particular interest because Columbia has been urging me to consider taking a leave of absence from Emory University, where I’m a professor, to spend a semester teaching on its campus.

But watching Barnard capitulate to mob violence and fail to enforce its own rules and regulations led me to conclude that I could not go to Columbia University, even for a single semester.

I conveyed this to Columbia’s administration on Friday, which prompted Columbia’s interim president, Katrina Armstrong, to call me. She pointed out that the two institutions, Barnard and Columbia, while affiliated, have separate administrations, security teams, and policies. I know this is true. But its recent history regarding demonstrations suggests that it has far less than a firm commitment to the free exchange of ideas, or to preventing classroom disruptions or even condemning disrupters and their demonstrations.

During the Barnard protest, Columbia issued an anodyne statement disclaiming responsibility because the “disruption” was on Barnard’s campus, not Columbia’s, and asserting its commitment “to supporting our Columbia student body and our campus community during this challenging time.” No condemnation.

This all occurs despite what I had seen as positive progress at Columbia. The university created an Antisemitism Task Force to explore the problem on campus. Led by three distinguished faculty members and with the participation of a number of longtime Columbia professors, the task force took its assignment with great seriousness and integrity. They interviewed hundreds of Jewish and Israeli students and repeatedly heard complaints that the university community has not treated them with the standards of civility, respect, and fairness it promises to all its students. Its report, issued in August 2024, makes for stunning reading. It found that the problems were “serious and pervasive.” The faculty members who wrote it did not flinch from facing Columbia’s shortcomings. They are trying to improve matters and deserve the administration’s, if not the entire university’s, gratitude and support.

Columbia’s Institute for Israel and Jewish Studies, and its Institute of Global Politics, a subset of its School of International and Public Affairs, are bright lights at the university. SIPA is now home to former Secretaries of State Mike Pompeo, Hilary Clinton and former Ambassador Jack Lew. Many outstanding Israeli scholars, shunned by other universities because they are Israeli, have found homes there.

My decision to withdraw my name from consideration for a teaching post at Columbia is based on three calculations.

First, I am not convinced that the university is serious about taking the necessary and difficult measures that would create an atmosphere that allows for true inquiry.

Second, I fear that my presence would be used as a sop to convince the outside world that “Yes, we in the Columbia/Barnard orbit are fighting antisemitism. We even brought in the former Special Envoy to Monitor and Combat Antisemitism.” I will not be used to provide cover for a completely unacceptable situation.

Third, I am not sure that I would be safe or even able to teach without being harassed. I do not flinch in the face of threats. But this is not a healthy or acceptable learning environment.

On too many university campuses, the inmates—and these may include administrators, student disrupters, and off-campus agitators as well as faculty members—are running the asylum. They are turning universities into parodies of true academic inquiry.

We are at a crisis point. Unless this situation is addressed forcefully and unequivocally, one of America’s great institutions, its system of higher education, could well collapse. There are many in this country—including those in significant positions of power—who would delight in seeing that happen. The failure to stand up to disrupters who are preventing other students from learning gives the opponents of higher education the very tools they need.

Meanwhile, absent direct and comprehensive action to protect Jewish students and the campus environment, I will not be teaching on Columbia’s campus.

Ambassador (ret.) Deborah Lipstadt was the United States Special Envoy to Monitor and Combat Antisemitism (2022–2025). Lipstadt teaches at Emory University as a University Distinguished Professor.

For more on antisemitism at Columbia, read Maya Sulkin’s piece, “Inside Columbia University’s ‘Museum of Terror’.”