The Free Press

This was a banner year for the bizarre and the profane up in the air: there was the man who cooked shrimp and mashed potatoes in a plane lavatory using a battery (we don’t know why, either), and the Southwest passenger who yelled at a crying baby. There was the Orlando-bound flight where a woman had a meltdown, screaming and claiming “that motherfucker back there is not real!” (without any indication of who or what she was referring to). And then there was the international Delta flight that was diverted after a diarrhea incident midair (honestly, the less said about that, the better).

The Sunday before this past Thanksgiving saw a record number of passengers: 2.9 million flyers in one day, a number not seen since 2019. It was also a record-breaking year for consumer complaints: between January and May 2023, the total number filed over missed connections, flight delays, and cancellations was 38,000—more than double the same period in 2022. Earlier this month, Southwest was fined $140 million for disrupting travel for two million people during the 2022 holiday season.

Nowadays—unless you have enough money to pay for a bit more space, comfort, and distance—flying is generally pretty miserable. And it has become worse in recent years.

It all raises the question: Does it really have to be like this? Absolutely not, says Ganesh Sitaraman, whose new book, Why Flying Is Miserable: And How to Fix It, lays out what went wrong with the American aviation industry. In the excerpt below, he explains how we got ourselves into this current mess and how to dig ourselves out. —Mackenzie Dawson

Flying is a miracle. For most of human history, it seemed like an impossible dream. But today we take for granted that we can have breakfast in Chicago and dinner in Los Angeles or see family across the country during Thanksgiving. We can conduct business anywhere. We can visit all the wonders of the world.

But flying is also miserable. Tens of thousands of flights are delayed and canceled each year. As a result, we’ve missed weddings, had our vacations shortened, lost time with friends, and skipped important meetings. When flights are on time, we pay extra to check our bags and then worry they’ll get lost. The overhead bin space seems to shrink every year—just like the amount of legroom. Delays might mean hours sitting on the tarmac, wishing for a drink of water or a snack or a chance to run to the bathroom. Or they can mean missing a tight connection and being stranded in an unfamiliar city. For those in cities with small airports or airports dominated by one big airline, minimal competition means higher ticket prices. For others, flying is a challenge because the airlines don’t serve their city at all. And all of us struggle to navigate the dizzying array of airline statuses and hierarchies, credit card perks, and point systems.

And that’s just the passenger experience. Zooming out, the airline industry faces a great deal of, well, turbulence. That turbulence has huge impacts on the country, cities, workers, and the economy. Consider these dynamics:

Airlines have gone bankrupt over and over again—and in recent years, merged over and over again. There are now only four big U.S. carriers (Delta, American, United, and Southwest).

In the years before the Covid-19 pandemic, the airlines made record profits. But when the pandemic hit in 2020, they needed huge public support programs—their second in twenty years.

In 2022 alone, more than 180,000 flights were canceled. Some were because of the Southwest Airlines debacle during the December holidays. But many others were a function of staff shortages or extreme weather at major hub airports.

Pilots, flight attendants, and other airline employees are often overworked to the point of exhaustion. Meanwhile, unruly travelers are an increasing problem.

Airlines are now reducing service from midsize cities, like Toledo, Ohio, and Dubuque, Iowa. In some markets like Cheyenne, the state capital of Wyoming, city leaders have even agreed to pay the airlines to offer service because, despite making profits, airlines refuse to fly there without a revenue guarantee.

The miseries of flying and the turbulence in the industry aren’t inevitable—and they aren’t just the result of the pandemic. Nor is this a simple story of corporate mismanagement. As varied as these problems are, they stem from a single source: public policy. We make choices as a country—through our elected representatives—about how best to govern our economy. We choose to have rules to ensure that food doesn’t have bacteria in it, that our rivers and lakes aren’t polluted, that toasters and cars and children’s toys are safe. We choose to have a whole set of laws so banks can get chartered, offer loans, and hold our money safely with a federal insurance system in case the bank goes under. In all these areas and more, we have historically chosen a regime of regulated capitalism that has enabled a thriving economy, but one with guardrails to make sure the dynamics of the market don’t lead to destructive harms. Businesses are supposed to follow the rules we set and be held accountable when they violate the rules.

The key question for air travel—or anything else—is simple: What rules should we choose?

Since the Wright Brothers first took flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, in 1903, the United States has tried three different approaches for governing air travel. During the infancy of flight, the federal government promoted the creation and growth of airlines, largely through subsidies. Once airlines were established, fierce competition led to industry chaos. Congress then adopted the second approach. It took a page from the American tradition of regulated capitalism and brought airlines under a system of governance akin to other transportation industries. The American tradition of regulated capitalism was built on the understanding that some sectors of the economy were not like others. Sectors like transportation, communications, energy, and banking were often network-like; they tended to become monopolies or oligopolies; and they could place extraordinary power in the hands of a small number of people and firms. Because of these dynamics, unrestricted competition wouldn’t work in those areas: it would lead to chaos or concentration. One solution is to nationalize businesses in these sectors. Indeed, some countries have had nationalized or publicly run airlines, trains, telephone systems, and electricity utilities.

But the American way was different. Instead of nationalization, these sectors were regulated as public utilities. Public utilities are essential infrastructure—critical for commerce, social life, and national security. Reliability and stability are paramount. From 1938 to 1978, air travel was governed under this regime.

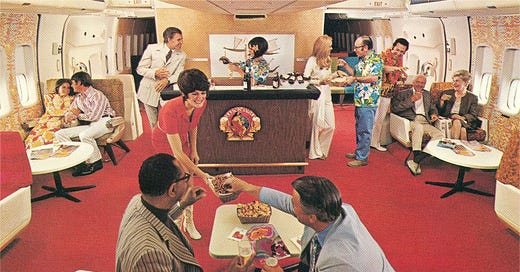

The American tradition offered a system of structural regulations that together achieved a variety of national goals. The system was designed to serve small and midsize communities; to prevent airline bankruptcies and bailouts; to ensure airports wouldn’t be dominated by one airline; to avoid monopolization and predation; and to maintain stable, reliable service at all times. It did this through a set of rules that included the regulation of prices, routes, and entry into the airline business. During this period, a relatively small number of highly regulated big airlines dominated the market. The legal system ensured that the airlines offered high-quality service throughout the country—and prevented the abuses that naturally come with limited competition. It was an age of regulated oligopoly.

In the 1970s, this system came under pressure from left and right, leading to the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 and a third approach to governance. Advocates for deregulation thought air travel was not a special sector akin to a public utility. They saw airlines as an ordinary market service, like selling sofas or running a convenience store, and they wanted to let the marketplace work. Through the elimination of structural regulation, anyone with resources could start an airline (or so they said), and airlines could pick their routes and set their own prices. Increased competition would lead to cheaper flights. Advocates didn’t think that deregulation would have negative effects on small or midsize communities or that it would lead to concentration into a tiny number of dominant airlines. They even claimed that after deregulation, there could be up to 200 airlines operating efficiently. At first, the deregulators looked as if they had been right. Opening up competition led immediately to a rush of new entrants, lower prices, and fare wars in the early 1980s. But by the end of the decade, the airline industry was in crisis: bankruptcies, low profits, higher prices in some markets, labor-management conflicts, a worsening flight experience, and increased congestion. Leading advocates admitted that they had misunderstood that airline markets are monopolistic or oligopolistic, that they didn’t realize how important scale was to the airline business, and that they didn’t foresee many of these ill effects. Some politicians even apologized for deregulation.

And the four biggest airlines ultimately ended up with an even larger share of the market than before—but now without the duties or restraints of the regulated era. Airlines had become an unregulated oligopoly.

We have now lived under this system for more than forty years. In that time, there have been 189 bankruptcy filings in the industry, major carriers have shifted pension obligations to the government, the number of major airlines has shrunk, and the government has had to bail out the industry. Fees are higher, seats are smaller, and the experience of flying seems to be getting worse.

Then came the pandemic. The Covid-19 pandemic revealed for everyone how problematic our system of unregulated oligopoly is. Before the pandemic, the big airlines were flush with cash, so much so that American Airlines’ CEO Doug Parker predicted it would never lose money ever again. American alone issued stock buybacks amounting to $12.4 billion between 2013 and 2019—more than its annual payroll in a given year. But when the pandemic hit, air travel ground to a halt. By April of 2020, passenger travel was down 96 percent compared with one year earlier. Without much of a rainy day fund, the once flush airlines asked Congress for funding to cover their payroll in the spring of 2020. Some commentators observed that airlines didn’t need this support. They had highly valuable frequent flyer programs they could use as collateral to get private sector loans. If private sector funding was insufficient, they could file for bankruptcy, as they had in the past. Doing so would not liquidate the company or significantly disrupt air travel. Congress rejected these arguments, given the airlines’ status as an essential part of our commercial infrastructure.

The CARES Act of 2020 was a critically important piece of legislation, designed to prevent the catastrophic collapse of the airline industry—and in particular, to save the wages and jobs of workers—by authorizing $50 billion in loans and grants. Under the payroll support program, airlines were offered up to $25 billion to cover their employee salaries and benefits without layoffs. This program was extended twice, with total authorized spending ultimately running to $54 billion. American Airlines took $12.74 billion, Delta $11.88 billion, United $10.89 billion, Southwest $7.1 billion. The program was transparent, protected workers, and prevented the airlines from profiting off taxpayer funds. Airlines couldn’t fire or involuntarily furlough employees until September 30, 2021, couldn’t issue stock buybacks or dividends, and couldn’t increase executive compensation.

But in a quest to cut costs, airlines offered early retirement and voluntary furloughs, leave, and reduced hours to employees. Thousands of employees took up these offers, which included cash severance packages and generous benefits. While technically legal, early retirements certainly violated the spirit of the law. The point of the payroll support program and its no-layoffs condition was to allow the airlines to weather the downturn.

When travel perked back up, they would be ready to fly without delays or disruptions. But when passengers did start traveling again, the airlines had too few staff. They canceled flights by the thousands. There were almost twice as many cancellations in 2022 as compared with the average over the prior decade. Airlines also pushed pilots, flight attendants, and ground crews harder. Pilots for some airlines were flying six days a week, and fatigue rates were 350 percent higher than before the pandemic. Airlines argued that the problem was too few pilots due to minimum flight training requirements. Proposals emerged to lower training standards and increase the retirement age to allow older pilots to keep flying. But these proposals overlooked both the most immediate problem—the early retirement packages—and the deeper ones—pay and training pipelines. As the pilots’ union observed, some airlines had more pilots than before Covid but were flying fewer routes and having a hard time recruiting pilots for low pay. And unlike foreign airlines, the biggest U.S. carriers had only started pilot training programs in the last few years.

With workforce shortages and tens of thousands of flight cancellations, the airlines started cutting back on routes, in some cases ending service to entire cities. In the fall of 2022, American cut 28,000 flights—17 percent of its flights in November. This included hundreds of flights from large cities like Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Smaller cities are seeing airlines depart altogether. Since the pandemic, American, Delta, and United have dropped 59 cities from service. For some cities, the departure of its only airline means no daily flight service whatsoever. In September 2022, Toledo, Ohio, a city of about 270,000 with a metro area of about 600,000 people, lost daily flight service when American ended its last remaining route. In the 1970s, Toledo had service from five carriers, and United alone offered eleven daily flights to seven different cities.

To individual passengers, these post-pandemic challenges are frustrating. But for the country, a broken airline system is a crisis. Air travel is a basic piece of infrastructure for society—like roads, electricity, or the internet. Whether for pleasure, tourism, or commerce, air travel is critical in the modern world.

With the pandemic in the rearview mirror, the verdict is in. American air travel is getting worse. We now have fewer flights to fewer places with less competition and higher prices—and with overworked pilots, flight attendants, and employees. The CARES Act succeeded in preventing the worst-case scenario: bankruptcies, further consolidation, mass layoffs, and the hobbling of the industry. But it was not designed to address the underlying problems with flying—problems that were growing worse well before the pandemic. The time has come to take a fresh look at what’s gone wrong in air travel and how we can make it better. We now have sufficient experience with deregulation—and distance from the turn away from structural regulation—to reflect more carefully on both approaches, assess their benefits and drawbacks, and consider new directions for the governance of air travel. We can choose to fix flying.

This article is an edited excerpt from Ganesh Sitaraman’s new book Why Flying Is Miserable: And How to Fix It, published by Columbia Global Reports.

Become a Free Press subscriber today:

The problem is that US airlines have a monopoly on domestic travel. In aviation this is known as cabotage. Because US airlines do not have to fear competition from external airlines, the larger carriers do not see a need to improve service standards or lower prices. It is actually a very interesting fact that at the time of the 1944 Chicago Convention which sought to liberalize air travel, the US who sought unlimited third (freedom to travel from one's home country to a foreign country), fourth (freedom to travel from a foreign country back to one's home country), and fifth (freedom to travel from one's home country, stopover in a foreign country and unload and taken on passengers and cargo before flying to another foreign country) freedoms, the US was unwilling to relent on cabotage (domestic travel, for instance between New York and Utah).

In 2023, 22.06% of all U.S. airline flights experienced some form of delay. That is 41 MILLION pissed off flyers. One fifth of flights being delayed is a staggering number, which causes ripple effects of sometimes expensive and devastating consequence to travelers.

Airlines are clearly not a typical form of public transportation akin to trains, for example. Flying represents a unique set of variables that will foil all attempts to make it more efficient as a public utility. Some things just aren't fixable by government intervention.

For flying to become pleasant again, the prices of flying must increase dramatically, and airports in smaller cities closed. The socialization and regulation of the industry, with intense pressures from all sides to democratize this mode of transportation, and maintain it as a public utility has resulted in the massive clusterf#ck we are experiencing. Flying is an awful experience.

The post office is on the way out. So is the massively regulated airline industry.