Last week the American Library Association (ALA) published its annual list of the “Top 10 Most Challenged Books of 2023,” claiming there is more censorship than ever on library shelves.

According to the ALA report, 4,240 titles were “targeted for bans” in schools and libraries last year, a record high and up 65 percent from the previous year.

But to reach these alarming findings, the ALA has distorted the facts. The ALA paints a picture of widespread censorship using a broad and misleading definition of “targeted” books. “Targeting” a book can mean any of the following:

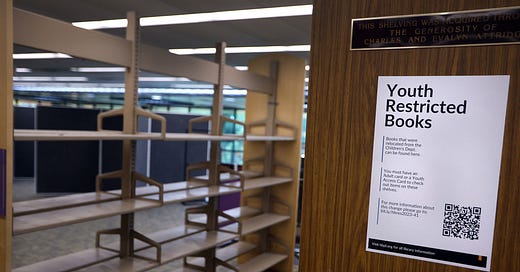

“Moving a book in the. . . young adults section to the adult section.”

In other words, ensuring that students are exposed to books that are age appropriate.

“Placing restrictions like parental consent rules on the book.”

Simply put, this means offering a parental opt-in, ensuring that parents have a say when their children want to check out a book that isn’t age appropriate.

3. “Taking the book out of the library altogether.”

This means removing a book that is deemed inappropriate from a taxpayer-funded library.

To frame all of this as a kind of censorship, or a ban, is dishonest.

And what is it that these parents are objecting to? The ALA’s own press release states that Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe—number 1 on its list—is “banned” because of “LGBTQIA+ content,” but parents and school board members tell me their concerns have nothing to do with the book’s “queer” author or characters and everything to do with its explicit sexual content, including the graphic sketches of oral sex found on page 167, something the ALA doesn’t acknowledge or address.

This is plainly inappropriate for children. The book’s stated reading age is “18 years and up” on Amazon, and 15 at Barnes and Noble.

According to the ALA, This Book is Gay—number 3 on the list—is also being targeted because of its “LGBTQIA+ content,” yet their list neglects to tell the full story: in addition to a chapter entitled “The Ins and Outs of Gay Sex,” the book explains how to upload photos to adult sex apps (pg. 156).

Again, is this really appropriate for children? Schools rightly restrict access to websites that feature this kind of content. Why should books be any different? Such steps should be uncontroversial, but instead the ALA wants to use them as evidence of anti-LGBTQ censorship sweeping across America.

Doing so isn’t just misleading; it’s a smear against parents who are rightly concerned about inappropriate content their children are exposed to at school.

James Fishback is a writer for The Free Press. Follow him on Twitter @j_fishback. And read his recent piece, “The Truth About Banned Books.”

To support our journalism, become a subscriber today:

First off, always check if they have a copy of Fahrenheit 451. If they don't then ask why. If they say it is inappropriate, then the school library definitely has a problem with banning books. If you don't know why, read it and research its history.

"It didn't come from the Government down. There was no dictum, no declaration, no censorship, to start with, no! Technology, mass exploitation, and minority pressure carried the trick... Today, thanks to them, you can stay happy all the time, you are allowed to read comics."

"But you can’t make people listen. They have to come round in their own time, wondering what happened and why the world blew up under them.'”

‘Remember, the firemen are rarely necessary. The public itself stopped reading of its own accord.'”

“A book is a loaded gun."

Its 1958, I want to check out The Untouchables (because of the TV show) from my library. I was to young the librarian told me.

Times have changed.