The Free Press

Toward the end of the 1982 movie An Officer and a Gentleman, drill instructor Emil Foley challenges his recruit Zack Mayo to a fight, and brings him to his knees.

“You can quit now,” Foley, played by Lou Gossett Jr., tells the bloodied Mayo.

It’s one of many hurdles the recruit, played by Richard Gere, endures on his long road to becoming a Navy pilot. And while the scene is brutal to watch, the audience understands that the experience is—in a way—necessary for him ultimately to achieve success.

Today’s armed forces are different—with the Pentagon now faced with a predicament:

The military can’t meet its recruitment goals. Too many young people are too fat, do drugs, or have a criminal record. This has been a problem for years. It’s now approaching a crisis.

To address the recruitment shortfall, the military has reduced previous standards for entry, allowing men to be 6 percent fatter (and women, 8 percent). It is also trying hard to lure recruits by appealing to their self-interest, with a video of individual soldiers speaking to the camera, encouraging candidates to find “the power to discover, to redefine yourself, to improve yourself, to challenge yourself” and “to realize there’s more in you than you ever knew that you could do.” Recruits can also win up to $50,000 bonus money for enlisting.

But this strategy carries a big risk: young adults tend to be less loyal to organizations with lowered standards that target their personal motives. Study after study has shown as much.

As the University of Toronto psychologist Paul Bloom has written, “If entering the group required a thumbs-up and a five-dollar entry fee, anyone could do it; it wouldn’t filter the dedicated from the slackers. But choosing to go through something humiliating or painful or disfiguring is an excellent costly signal, because only the truly devoted would want to do it.”

In other words, by lowering the barrier to entry, the military has opened itself up to more recruits like Jack Teixeira.

No one knows exactly why Teixeira, 21, the Massachusetts Air National Guard airman, allegedly leaked classified information about the CIA, exposing our intelligence on Russia, South Korea, Israel, and Ukraine. He is now cooling his heels in prison, charged with violating the Espionage Act for spilling state secrets on the gaming platform Discord.

The Tucker Carlson right and the Glenn Greenwald left have come to a similar conclusion: that Teixeira is a kind of folk hero. Greenwald recently stated that, much like Edward Snowden, Teixeira aimed to “undermine the agenda of these [intelligence] agencies and prove to the American people what the truth is.” And it’s hard to imagine any Republican ten years ago making the argument that Marjorie Taylor Greene did—that the “Biden regime” considers Teixeira an enemy of the state because he is “white, male, [C]hristian, and antiwar.” Regardless of their specific reasons, this bipartisan agreement that Teixeira should be applauded is emblematic of a broader lack of confidence in the American government and our military.

In recent years, support for the military has plummeted more than in any other American institution—with 45 percent of Americans voicing trust in the armed forces in 2021 versus 70 percent in 2018. This decline is almost entirely due to younger Americans: among those 18 to 44, confidence in all the branches of the military is in the low- to mid-40 percent range; for those 45 and up, it’s in the 80 percent range, according to a 2022 YouGov survey.

This decline in support for the military coincides with declining patriotism among young Americans: 40 percent of Gen Zers (those born from 1997 to 2012) believe the Founding Fathers are more accurately characterized as villains, not heroes, according to psychologist Jean Twenge’s forthcoming book, Generations.

You might think that the young Americans serving in the Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marines are immune to these opinions, that their decision to enlist implies a deeper bond with America and the military sworn to protect it.

You’d be wrong.

The evidence is in the advertising employed by the military itself. Recruitment campaigns seldom appeal to higher values, or to the history of the United States and its innumerable achievements. Rather, they appeal to the self. More and more young people are asking not what they can do for their country, but what their country can do for them.

I saw it myself when I enlisted in 2007. Even amid two wars, in Iraq and Afghanistan, recruiters from all military branches boasted of enticing benefits, career advancement, and the chance to acquire new skills. There was scant talk of patriotism or service to the nation.

That said, I sensed at the time that service members were more patriotic than the general population.

But that gradually changed. In 2013, there was a huge outcry when the military suspended tuition assistance, which had previously covered 100 percent of college tuition fees for active duty members who took night classes. One of my coworkers proclaimed, “Why the fuck did I even join?” This was perplexing to me; we already had the GI Bill. For many people, that wasn’t enough.

By the time I left the military in 2015, I noticed a subtle difference among new members, who seemed most interested in pay raises, the chance to travel the world, and other benefits.

This has been building for a long time.

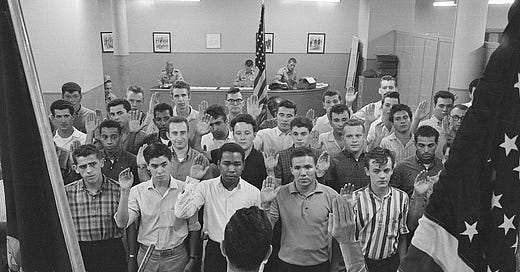

For both World Wars I and II, Uncle Sam famously pointed his finger at potential recruits and declared, “I want YOU for the U.S. Army.” The noble ideals of the time were ones of service and self-sacrifice.

Then, starting in 1980, in the wake of Vietnam, the Army shifted to “Be All You Can Be.” That lasted until 2001, when the slogan was updated to “Army of ONE.”

In January 2020, The New York Times reported on the Army’s latest marketing campaign, which spotlights its generous tuition benefits (especially alluring to young people crushed by student debt), and the opportunities that an Army stint would lead to in medicine and tech. Its messaging also stresses that most jobs are nowhere near a combat field, according to the Times.

In March 2023, the Army reinstated the slogan “Be All You Can Be.” (Although the Army did release a commercial, “Overcoming Obstacles,” that touts the military’s major historical achievements, it was yanked after its star, actor Jonathan Majors, was swept up in domestic abuse allegations.)

Nevertheless, the idea was (and is) clear: the goal of the military is not to defend something bigger and more consequential than any one person. It is to achieve yourself.

Self-interest might work in the short term to boost recruitment numbers, but it is misguided if the aim is to recruit properly dedicated people. The requirement to overcome self-interest is what cultivates loyalty and weeds out unserious candidates.

In his 2022 book, Ritual: How Seemingly Senseless Acts Make Life Worth Living, the anthropologist Dimitris Xygalatas argues that the number of difficult requirements imposed by a community correlates with a longer life span of the group. In short, the higher the price of membership, the longer the group survives. This is one reason why sports teams, fraternities, and militaries are hardest on their newest members. Imposed suffering builds bonds and filters out potentially disloyal members.

We shouldn’t be lulled into complacency by our current military dominance. As Cold War historian John Lewis Gaddis has noted, military power tells us only so much about how strong we are as a nation. Exhibit A: the Soviet Union, which, Gaddis observed, enjoyed its greatest military power at the very moment it was falling apart, in the early nineties. The problem, Gaddis explained, was the country had lost its sense of conviction or purpose—and the loyalty of its citizens.

If people no longer believe in the country, then its future is finished.

To state the obvious: we want more Zack Mayos and fewer Jack Teixeiras—more recruits who have to fight to fit into and rise up through the military, and fewer who are simply using the military to get ahead. More recruits who will strengthen the body politic, and fewer who will endanger it. (As we learned Friday, Teixeira had, in fact, been leaking classified documents to a wider audience and for longer than originally thought—stretching back to the start of the Ukraine war, in February 2022.)

Ultimately, the United States cannot rely on money and military power alone to sustain itself. Our nation’s strength depends on the unwavering commitment and unity of its people.

Rob Henderson is a columnist for The Free Press. Follow him on Twitter at @robkhenderson and subscribe to his Substack here.

And for cultural commentary you can’t get anywhere else, become a Free Press subscriber today:

I served 12 years in the Navy. Got out in 1997. I would NEVER join the military now. Our government is completely corrupt and evil. We are war mongerers. With the internet and abundance of information we have now we can all see clearly how malevolent and self interested our leaders and BOTH parties are.

Sadly we are raising a bunch of wimps. My opinion. I am in healthcare and the difference in the attitude at the workplace is shocking sometimes. Personally, I don’t think it’s the military people don’t trust but the leadership, and our government is in really bad shape. Heck, I’m soon to be 70 years old and I am disgusted with our government including the DOJ, FBI, MILITARY, HOUSE & SENATE. AND don’t get me started on the current administration. We are in deep you know what.