What September 11 Revealed

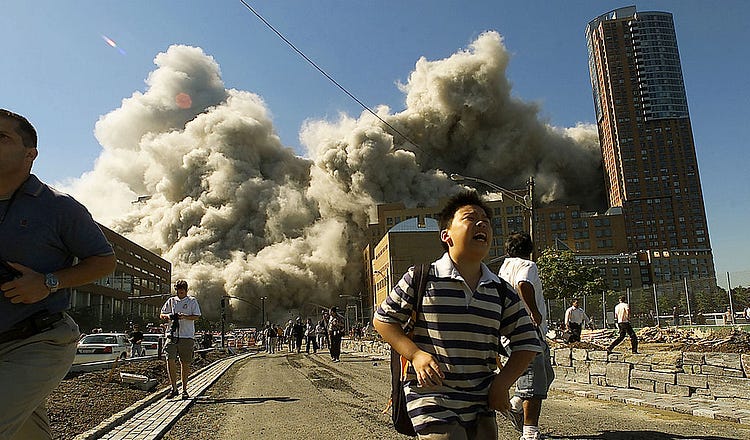

People run away as the North Tower of World Trade Center collapses after a hijacked airliner hit the building September 11, 2001, in New York City. (Jose Jimenez via Getty Images)

A writer looks back at a portent of the future.

225

Twenty-three years ago, not long after the murder of nearly 3,000 innocent Americans on September 11, The New York Times Magazine asked me if I would write about antisemitism. They had noticed the explosion of Jew hatred that seemed to have ridden in on the contrails of the airplanes that jihadists had turned into weapons of mass destruction and aimed a…

Continue Reading The Free Press

To support our journalism, and unlock all of our investigative stories and provocative commentary about the world as it actually is, subscribe below.

$8.33/month

Billed as $100 yearly

$10/month

Billed as $10 monthly

Already have an account?

Sign In