The Free Press

Fun seemed to have come to an end on October 7 here in Israel. Amid the endless stream of tragedy flooding our phones and seizing our attention, it felt almost unconscionable to laugh. But for the cast and crew of Eretz Nehederet, which translates to Wonderful Country, Israel’s prime-time sketch satire show—our version of Saturday Night Live—generating humor is a duty.

“After October 7, our discussions and plans for the next season came to a halt,” Reshef Shay, a writer on Eretz Nehederet, which airs Tuesday or Wednesday each week on Keshet’s Channel 12, tells The Free Press. “Our program runs tightly to what’s going on day to day. So when reality changed, let’s just say, we write jokes and God laughs.”

Eretz Nehederet aired 19 days after October 7—the same time it took SNL to go back on the air after 9/11. Then-mayor Rudy Giuliani, from whom SNL’s producers sought permission and approval before premiering, opened the show, flanked by 9/11 first responders. Alicia Keys performed. Reese Witherspoon hosted.

Eretz Nehederet’s first wartime episode—the show has been running for twenty years— skipped the sentimentality. In one sketch, an army captain welcomes reservists with an upbeat roll call as they board the army bus.

“Anarchists? Bibi-ists? Traitors?

“Racists, you here? Poors?” she calls out in Hebrew. “I’ve missed you guys!”

The episode went on to send up key characters and tropes from the past two months; Israeli prime minister Benjamin “Bibi” Netanyahu, Greta Thunberg (who has morphed from climate crusader to pro-Palestinian activist), and nouveaux riche Israelis who’ve taken to bringing extravagant meals to soldiers at dingy army bases.

“I woke up on October 7, made some calls, and immediately started a nonprofit,” boasts a flashy, Rolex-wearing man as his blonde, buxom wife explains the concept of farm-to-table dining to a group of confused soldiers in one skit.

“The whole country is still deeply in grief,” says Muli Segev, Eretz Nehederet’s executive producer. “Every one of us has lost someone, or knows someone who has. But people need relief.” Although some voices, including within the production team, believed it was too soon or too inappropriate to air the show, Segev went ahead.

The episode that aired was the first non-news broadcast on Israeli TV after October 7, and 28.6 percent of the nation’s households watched live—Eretz Nehederet’s highest numbers in years. Since then, there have been five episodes that have taken sharp aim at a handful of institutions: the BBC, Columbia University, the UN.

Some sketches have gone viral overseas, especially on Americans’ screens, including a clip where two pink- and blue-haired Columbia students, one in a keffiyeh, rip down posters of kidnapped Israeli children while one beseeches the viewer: “I’m not antisemitic, I’m racist-fluid!” The clip amassed over 5.3 million views on Instagram.

Eretz Nehederet doesn’t shy away from the dark or self-deprecating; race, gender, politics, religion, and money are all fair game. Obscenity and provocation aren’t a liability—they’re the point.

In another viral sketch, a BBC anchor urges on the Gazan death toll as it jumps from 500 (“More, more!”) to 750 (“Much better”) after a bombing. She then throws to Middle East correspondent Harry Whiteguilt, who describes Hamas as “the most credible not-terrorist organization in the world.”

“It’s the old Jewish secret: laughing in the face of death,” said Segev. “But I admit this time was harder than ever.”

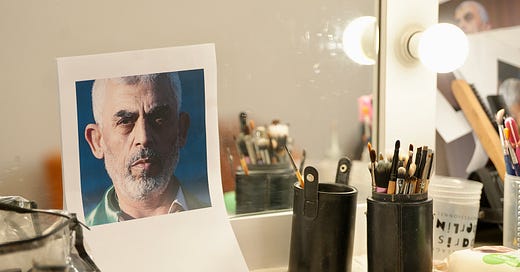

In one sketch, a BBC anchor interviews Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar, who is being kept up at night by a hostage child “occupying” his house. (“So unfair,” the anchor offers.) But rehearsing the sketch—which included the sounds of a crying baby—was so difficult for the actor playing Sinwar, he couldn’t get through it without crying himself. So the sounds of the child were added post-production.

Eretz Nehederet’s character “Asher the Cabman” is famous for being a loudmouth caricature of an Israeli taxi driver, and known for roasting his backseat charges—real-life Israelis, not actors—over everything from religion to politics. In a recent episode, Asher, played by Yuval Semo, took the displaced families and relatives of hostages for a ride. Amid the survivors’ distressing testimonies, Asher squeezes in friendly barbs and jabs until one young man shares that his parents were both murdered in Kfar Aza. He said his father had loved the taxi bit, and dreamed of being in the backseat himself.

“For the first time,” admits Asher the taxi driver, “I have no words.”

After another woman shares that her husband was killed protecting their kibbutz, Asher stops the car, climbs into the backseat, and gives her a hug.

Lee Kern, who co-wrote the sequel to Borat and the Showtime series Who Is America, had a recent guest credit on the November 14 episode of Eretz Nehederet. “I’m more proud of that than my Oscar nomination,” he told me. “I’ve become very jaded and cynical about comedy. About its purpose and all the vanity around it,” he added. “But now it feels different. I feel for the first time that my comedy makes sense. These are the people I want to make laugh.”

He says comedy, in the wake of October 7, is “spiritual first aid,” adding that the best strategy when it comes to bullies is “taking the piss out of them.”

But how far is too far? The show skewered Israel’s far-right minister Itamar Ben-Gvir last year with a parody of Springtime for Hitler—and in 2016, it mocked ISIS as a jaunty, jihadist boy band at Eurovision. Since the war, the writers are carrying extra weight on their shoulders. “It’s like a normal day,” mused Shay, the staff writer, of their process. “We have creative meetings. We throw ideas. But now it’s much more intense.”

The writers are constantly exploring what’s kosher to joke about—and what’s out of bounds. “What’s most sensitive?” Shay posed. “What’s most important?”

“You must cross the line. You must cross it to discover the line,” Shay said.

Fans of the show say watching it lately has been like a national Prozac pill. “Their humor allows us to start processing the trauma,” says Yarin Singolda, an Air Force reservist living in Tel Aviv. “Otherwise, it would have taken us ages to figure out how to start a conversation about Israel’s darkest moment. Even with ourselves.”

Taking it a step further, Australian Israeli journalist Gabbi Briner says the show is giving Israelis what the flailing government has failed to provide since October 7: support, assuredness, and a sense of unity.

“I swear,” said Briner, “Eretz Nehederet is the Israeli institution with the highest level of public trust right now.”

Polina Fradkin is a writer and singer based in Tel Aviv.

Our work is made possible by subscribers. If you appreciate our cultural coverage, sign up today:

This is incredibly funny.

https://youtu.be/xcLCe5iBvVc?si=is4TwiwF5-CzxHuM

Thank you for calling out Claudine Gay's treatment of Roland Fryer. You made a mistake in calling her part of a Cabal that led to his suspension, she led the cabal. She forced a 2 year suspension, forced the shutting down of his education lab and tried to have his tenure revoked. Why? Because research he conducted in Houston showed that police were less likely to shoot black suspects than white ones. It also showed that they were more likely to use force with black suspects. He's back at Harvard now but can only teach undergraduate students and cannot serve as an advisor.