The Free Press

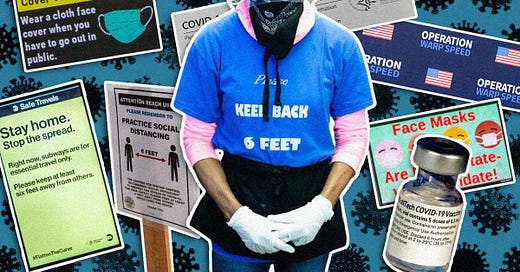

For the last few weeks, the media has been filled with stories about what The New York Times has described as our latest “viral onslaught.” It’s been dubbed a “tripledemic”—a combination of Covid-19, influenza, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), which is being blamed for high rates of illness and an excess of hospitalizations, especially among children.

The message is clear: fear winter respiratory viruses, and take every possible precaution you can. It’s time to slap on those N95s once more, avoid crowds, and socialize outdoors if possible.

But the best available evidence contradicts the narrative from the media and many public health officials. The precautions being recommended are essentially unproven—akin to burning an incense stick, or wearing garlic to ward off vampires.

The way to think of the tripledemic is that it’s just another example of what we used to call normal life. And the insistence on never-ending precautions in the face of inevitable exposure to germs is not only medically misguided, it also threatens to stigmatize the most mundane human interactions.

In the case of the tripledemic, there is one action the media and its favored experts want more than anything else: increased masking. Philadelphia schools have returned, temporarily, to masking children, including toddlers in Head Start. Two New Jersey school districts are requiring the same from pre-K until 12th grade. Boston Public Schools are asking students, teachers, and staff to wear masks (but will not discipline those who don’t). Boston Mayor Michelle Wu said the masking “will help keep our kids safely in the classroom with their peers.”

Dr. John Swartzberg, an infectious disease expert at UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health, told Reuters: “If you don’t want to get sick and you don’t want to go to the hospital and you don’t want to die of Covid or influenza, or if a very young child, RSV, then you should be wearing a mask indoors in a public place.”

The California Department of Public Health agreed, tweeting: “There is no vaccine for RSV, so wearing a mask can significantly slow the spread and protect babies and young children who do not yet have immunity and are too young to wear a mask themselves.” (The advice, for which there is no data, has since been removed without explanation.)

There are three important points to make about the tripledemic:

There is limited evidence that it exists.

There is no avoiding respiratory viruses.

There is no evidence that prolonged precautions delay the inevitable.

First, let’s consider the evidence of the so-called tripledemic. Although flu season began early, there is limited evidence that it is worse than typical years. Dr. Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, says: “It feels like it’s bad because hospitals are so understaffed, but this does not represent an outlier season.”

RSV, which is a standard childhood illness, also surged early, and it generally hits very young children and the elderly hardest. There are ongoing shortages both in terms of medicine, like Tylenol, and pediatric hospital beds. But the latter is less about the rising cases and more about the disappearance of pediatric services. Caring for children is not a major moneymaker for hospitals, and often earns less than adult hospitalization. Over the past two decades, as The Washington Post explained, there has been a major decline in pediatric beds nationally. The bottom line: we should be less afraid of RSV and more concerned about our broken ability to handle routine viral illness year to year.

Second, there is no avoiding respiratory viruses. With extreme, draconian measures, exposure to respiratory viruses can be delayed, but can never be averted. This is in contrast with, say, our ability to avoid contaminated drinking water or sexually transmitted diseases. The difference is that human beings have to breathe every minute of every day. And, as humans are social creatures, most of that breathing will naturally be very close to other human beings.

“The piper must be paid at some point in nature; kids will get sick, and it has nothing to do with a more compromised immune system,” says Dr. Danuta Skowronski from the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control.

This point must be emphasized. It is natural, healthy, and necessary for young children to be exposed to many viruses. In order for children to build immunity to common pathogens—in order for them to develop a normally functioning immune system—they must have such exposure, which will sometimes make them sick.

And third, there is no evidence that the interventions purported to stop Covid-19, flu, and RSV will help. Before Covid-19, the evidence to support masking was thin. I co-authored a survey of masking trials that were done prior to the advent of Covid-19, examining whether masks stopped transmission of respiratory viruses. Fourteen of the 16 trials showed masks were ineffective at this. In other words, the pre-Covid evidence was clear that recommending masks for the average person was useless. This is likely one reason why Dr. Anthony Fauci, the CDC, the World Health Organization, and others initially advised against masking.

Even worse, the evidence for masking young children for Covid-19, flu, and RSV viruses is entirely lacking.

The two best studies on the topic take advantage of natural experiments. One experiment, in the Catalonia region of Spain, looked at the effectiveness of masking children to prevent Covid-19. The authors took advantage of a unique fact: that children six years and older in this region wore masks and those younger than six did not. If masking had a protective effect, then kids just younger than six years would have higher rates of Covid than those just older. But there was no such pattern. In a separate analysis in Finland, the authors compared two towns with different policies for kids between the ages of 10 and 12. One town masked, the other didn’t. There was no benefit seen from masking there either. The spread of Covid-19 was identical. There was no difference at all.

Additionally, at this point, at least 9 out of 10 American kids have already had Covid-19. We know that having had and recovered from Covid-19—which confers what’s known as natural immunity—doesn’t mean you will never get Covid again. But if you were to, the odds are that it would be milder and less severe. Masking kids who had Covid-19 is pointless in two ways. One, there is no evidence to suggest that it will delay the time until they get it again. Second, it’s being done to prevent something that—for them, at this point in the pandemic—is usually less severe than the common flu or even some cold viruses.

So what is the tripledemic in reality?

Covid-19 disrupted all aspects of life. It disrupted immigration, travel, business, education, religious practices, family life—society itself. Some of these disruptions interfered with the spread of respiratory viruses like RSV and flu. The fact that Covid-19 continued to spread despite all this is a testament to how contagious it is, especially in a population that had at the time essentially no preexisting immunity.

Now, as the disruptions fade, other viruses have inevitably returned. Hospitals should prepare for this. If pediatric beds are what’s in short supply, federal reimbursement should pay for pediatric beds. This would entice hospitals to expand capacity where it is needed. That’s a more productive solution than suggesting people withdraw from gatherings, or remain masked in perpetuity. Three years into the pandemic, we face a crucial question: How do we want to live the rest of our lives? Like most Americans and as a doctor, my answer is resounding: as normal.

Read more of Dr. Vinay Prasad’s work here. And let us know what you think of today’s piece in the comments.

I'll confess t some confusion. On the one hand I'm told that masks are ineffective because people don't wear them properly while on the other I'm told that masks don't work and that the statistics support this assertion.

If case one is true, then case two has already been invalidated, or at the very least brought into question.

This article is a great example of why I LOVE The Free Press and subscribe .... reporting that provides CONTEXT on an issue. Thank you Dr. Prasad for providing the background information on the "Tripledemic" that the legacy media just will not do or is not interested in doing.