The Free Press

“I think Trump may be one of those figures in history who appears from time to time to mark the end of an era and to force it to give up its old pretenses. It doesn’t necessarily mean that he knows this, or that he is considering any great alternative. It could just be an accident.”

—Henry Kissinger, July 2018

The “great man” theory of history lost favor a century ago, and for decades university faculty have found it quaint, vulgar, or problematic. Like other ideas that right-thinking people long ago discarded, its disreputable status hasn’t stopped many from believing in it anyway.

We’ve all heard before that Donald Trump is a pragmatist, a man of action and not ideas—he did not write a manifesto before coming to power or spend an exile in Vienna (or even Florida) developing revolutionary theories. He spent his adult life developing buildings in New York City, then starring on a reality TV show that cast him as a merciless and instinct-driven businessman.

Yet despite Trump’s lack of an explicit ideological project, or maybe because of it, his rise has coincided with a new energy in right-wing intellectual life. It didn’t start with him; some of the public intellectuals, opinion shapers, and radical bloggers who are now associated with Trumpism were writing about politics long before Trump, and have merely found in his paradigm-breaking success an opportunity to assert new ambitions. There is, however, a younger generation, who were children when Trump first ran for office, and whose political imaginations were ignited by his rise to power. They have no memories of belonging to—or being accepted by—any party or cultural milieu except Trump’s. And for them, Trump is not just a disrupter, an excuse, a historical symptom, or an accident.

A few months before the 2024 election, Gen Z young men who were leaning toward Trump were described in The New York Times as “apolitical” and adrift; when their demographic achieved new prominence via exit polls, it was implied they had been manipulated into Trumpism by “bro whispering” podcasts.

Maybe this was true for some. It was not true of the young, mostly male and intellectually curious Trump voters who I encountered last July, during a reporting assignment to cover two overlapping conferences in Washington, D.C.: first, the fourth installment of the National Conservatism (NatCon) Conference, and then the Liberalism for the 21st Century conference, organized by the Institute for the Study of Modern Authoritarianism. The young men I met at NatCon—and who I kept up with throughout the summer and fall—were far from apolitical, and they showed no signs of being easily manipulable. In describing how they had arrived at their political outlook, none of them cited podcasts.

I attended these conferences as a young person interested in ideas. I arrived with no bias against liberals, or toward post-liberals and national conservatives. Raised by immigrants just outside of the District in liberal counties, and coming of age at the end of Barack Obama’s liberal renaissance, I spent my college years—and Trump’s first term—on a progressive campus in California. Since graduating in 2020, I’d worked at large government agencies and mainstream think tanks. But like many young people all over the country, I had been searching for ideas beyond the technocratic liberal consensus. Because of this, I became part of a politically mixed social scene in D.C. and had discovered, with at least a little discomfort, that despite the 20th-century liberal occupying the White House, the intellectual vitality in my generation was increasingly to be found in post-liberal or conservative spaces—in other words, on the right.

Even still, I expected to find something of a political sideshow at NatCon; instead, I found a movement, perhaps the only one I’d encountered during my time in D.C.

There is no dress code at NatCon, but somehow everyone, young and old, was dressed to the nines. Many attendees looked like extras in American Psycho. It was a hot summer, but I saw tailored wool and linen suits, tastefully patterned burgundy, ultramarine, and violet silk ties; and pocket squares on 20-year-old men. There are hundreds of young men here, and plenty more are turned away at the registration table; they tried to sneak in anyway. Several asked me to help get them in: Among these were foreign interns visiting over the summer, young private-sector professionals, college students.

On the first morning, I was approached by a young man dressed in a nice gray suit, who offered a handshake, mentioned he’s a student at an Ivy League school, and clumsily added that it would be his first semester this fall. I realized that he must have graduated high school only weeks before. He had chosen to spend part of his last summer before college here, at this political conference at the Capital Hilton.

He asked for my LinkedIn, and I reached out to him in the fall, after the election. “I was 10 when he first announced he was running for president, and he just captured my attention,” he says. “I’d always been fascinated by politics and history, obsessed with world leaders. . . . I think that there’s a certain element of greatness in Trump’s personality.” And then: “I’ve always seen myself in him. That’s the first thing that drew me to him when I was 10. I’d always been admonished in school by my teachers . . .”

He pauses. “Well,” he laughs, “this is a little silly. But when I was little, I always wanted to do something great, and I would talk about that when I was a kid. And I’d have teachers and other people telling me: ‘You can’t say that; you shouldn’t be so full of yourself.’ And then this guy comes onto the stage, eschewing all of these norms that people expected him to follow, just going out there and saying, ‘I’m a winner; the people who are running this country are doing a bad job. I’m the only one who can fix it. Put me in there, and I can make America great again.’ I looked up to Trump when I was little in the same way that maybe a kid in France might’ve looked up to Napoleon 200 years ago.”

Lucas (his name and the names of the other young men I spoke to have been changed) was born in 2005 and raised in a “typical” and “apolitical” family outside of Philadelphia. “I’ve never in my life remembered a time when the Democratic Party supported ambitious people,” he says. “I think their whole ideology is based off of oppressing those with ambition, who actually have the gumption to go out and do something and build something on their own . . . the people who make humanity great: the innovators, the builders, the winners in society. They look at the winners and tell them, ‘You’re evil, and the only reason you’re at the position that you’re at is because you exploited other people.’ It’s antithetical to the way that a lot of young men work.”

But, I ask him, What do young men who aren’t aspiring to be “innovators, builders, and winners” think of Trump?

“A lot of the guys who I went to high school with weren’t particularly ambitious career-wise, but they do admire people who are. They all admire Trump for what he’s done,” says Lucas. “All young men, even if they’re not actively trying to be great, still admire greatness,” he continues.

Trump, Lucas explains, is a role model: “He wins against all odds. He gets impeached, he gets criminal trials thrown at him, shakes all that off. He gets shot. The fact alone that he got up and pumped his fist—that takes a lot of physical courage in itself.”

I ask Lucas if anyone else at NatCon, including Vivek Ramaswamy or J.D. Vance, the former of whom he got to meet, inspires him. “I really like them. They’re sharp guys; I like their policy. But I don’t really think there’s anybody else like Trump.”

It was the 45th president who proved to him that his dreams were possible, no matter the opposition. “Hopefully I can strike it big in the private sector,” he says, “and then, if everything were to go right, I would like to be president someday.”

Alex is a lifelong conservative, and unlike Lucas, has no political or entrepreneurial ambitions whatsoever. Soon after the end of NatCon, I found myself at a party with him the day Trump was almost assassinated in Butler, Pennsylvania.

The crowd at the party was politically mixed: There is the liberal son of a prominent Democrat, the editor of a right-leaning policy journal, a think tanker, a liberal libertarian—a more or less typical sampling of the D.C. social scene that exists for those who don’t mind being around different political persuasions. (These ecumenical events, revealingly, often skew right.)

We barely enjoy refreshments and cocktails before the news spreads: Donald Trump has been shot. One guest spends the rest of the party apparently comatose or on Twitter; others (including young conservatives) continue as normal, trying to avoid the subject; a summer intern and aspiring Trump administration staffer begins filming his live response on his smartphone. At the end of the night, Alex turns to me, and asks, “The party was fun, really. But why does no one care? They nearly killed him.”

After the election, I press him to explain what he meant that night. “I personally identified with him,” he says. “The extent to which they were trying to stop him represented the extent to which people have tried to stop me.” By “me,” I think he means young men like him. Alex’s formative college years were spent in the political fallout of Trump’s first presidency—cancellations, Covid lockdowns, nationwide protests, and political violence; his short academic career, now over, had been characterized largely by the proliferation of DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) and anti-racism initiatives.

“When Trump became the Republican nominee, conservative people, especially conservative young people, found themselves in the position of our peers attacking him by proxy through attacking us,” Alex says. “There’s a line Trump used—‘They’re not going after me. They’re going after you. I’m just in their way.’ Young men experienced that almost in reverse a lot of the time, when people who were our friends, who were our peers, would just relentlessly bully us, cancel us, harass us, physically assault us because of Trump.”

I think back to Lucas’s description of his fall 2024 semester, his first on his Ivy League campus. He told me that because he’d been outspoken about his support for Trump, “sometimes people will just look at me, give me the finger, and say, ‘Oh, fuck you, fascist.’ Half these people who tell me to go fuck myself, I have no clue who they are.”

Alex, who began his college career two terms ago in a culture also charged by Trump’s electoral success, continued: “And to see him almost get killed, and almost get killed in an astonishingly gruesome and public way, felt like extraordinary evil almost triumphed.”

He recalled the events of not just this past summer, but of the years that preceded it: “In human history, has there been, mathematically speaking, an assassination attempt that was so narrowly avoided? The sheer geometry of it—nothing like it has ever happened in the history of the world. And nothing like him has ever happened in the history of the world. Look at this well-known celebrity, who just says, ‘I’m going to become the most powerful man in the world.’ And then wins a democratic election. And in doing so, faces the collective force of essentially the entire world and indeed his own government, faces criminal indictments in however many jurisdictions, absurd civil fines, attacks from all angles, and then is a quarter of an inch away from his head exploding, to then somehow winning again? That gives him a . . . I’m not going to say messianic, but anointed sense. We do not understand the goals of whatever or whoever decided that it would be so, but there is something happening here beyond our understanding.”

Alex grew somehow even more passionate, urging me to understand why he cared that night in July: “The drama of how close he was to death and just his immediate response. . . . You look at that and you think, How else can you explain that except by some supernatural means?”

I think I get it now—how upset he seemed that night; how odd, and surprisingly emotional, I found it at the time. I merely thought Trump was a big joke—even if he had exposed a failed consensus. I realize that, to many, he is no laughing matter, and to others, as Alex put it, someone of “quasi-religious significance.”

“I was reacting to it the way people must have felt when they saw the careers of Bonaparte, Caesar, Alexander, Washington,” Alex finished explaining. “Young men are primed to look at the great men of history, especially those young men who care about tradition and the past, in terms of greatness and anointed-ness, and there is obviously no one else like him who has existed in our lifetime or will exist again.”

I think I’d taken the end of history for granted; I’d wanted peace as much as these young men want someone to defend them. I never once conceived of Trump as a world-historical figure marked by greatness. I think, perhaps, we get the great men we deserve.

Young men like Lucas and Alex make up about 90 percent of an informal group of conservative Hill staffers, think tankers, and young professionals who host debating parties around Washington. Between NatCon and the election, I attend several of the debates. The young men give eloquent, sometimes sophomoric, but always earnest speeches at whatever venue they can find, and they do it all for free—they even chip in to keep the parties going. The men wear tailored two- and three-piece wool suits and matching pocket squares, and the (few) women wear cocktail dresses; there’s apparently nowhere they’d rather be on a Saturday night.

These young intellectuals call themselves—like 19th-century Romantics—“sensitive young men.” At the after-parties they discuss metaphysics. Though conversations in D.C. often begin with the tiresome phrase “What do you do?,” at this party, no one is defined by their day job. It’s obvious, however, that some of the best congressional offices on the Hill, several conservative magazines, and the city’s universities are well represented. I instead know what these young men think about free will and contingency; about ancient history and European Union regulatory disputes. Among them I’ve heard discussions of 20th-century espionage and quotes from Kissinger, Freud, Kierkegaard, Homer, Virgil, Montesquieu, and The Federalist Papers. They revive the best parts of their undergraduate curricula and try their best to cultivate serious intellectual lives. They also impose strict rules, among them a complete prohibition against phones on the debate floor. And outside their meetings, they’ll read whatever they think is honest, real, and intellectually meaningful, no matter where it is published.

A couple members of this debating group introduce me to an essay in The Point, about love: “Lovers in the Hands of a Patient God.” I’m touched by it,—it’s the first essay I’ve read in a long time that treats love, and sex, as meaningful and sacred—and from a secular, liberal perspective. It speaks to their exact concerns: how to live a good life, find love, cultivate meaning, make life’s great choices.

I don’t come for the debates themselves—which can be boring or ridiculous. But like these young men, I’ll go wherever people want to discuss ideas vigorously. The casual conversations I have here are among the best I’ve had outside of academia. Here one needs no excuses or credentials to be part of grand discussions about history, philosophy, and art. I often encounter a disarming honesty, and not just about politics or history: after a long verbal sparring match with a friend, I see a young man from California look away wistfully and say, “I just want a girlfriend.”

The debate nights took me back to my own undergraduate days, and everything I looked for, and often failed to find, then.

In early 2017, I asked the “secular humanist chaplain” at the University of Southern California, where I studied, how I could set myself up for a good life in college and beyond. How could I be happy? How could I find a vocation or a calling? How could I be a good person? The chaplain told me to look around and identify the people who had lives I wanted to live, and ask myself what their values were. I quickly realized those moral exemplars were not in the secular student group I’d joined, which had become morally vacant and pseudo-rationalist. To say nothing of love: More and more of my female friends at the time were embracing polyamory to justify situationships or infidelities, while being told in seminars that monogamy was a colonial construct and should be discarded. As a young woman, and as a child of divorce, my primary concern was having models for healthy relationships—not resisting colonialism in my dating life. I had no interest in subverting things—monogamy, moral norms, courtship, the nuclear family, faith, a classical education—that I’d scarcely known in the first place. I wanted a serious boyfriend.

Other liberal students and professors, if they had accomplished some degree of personal success, whether wealth, erudition, or relationship satisfaction, dared not talk about it, since it would put them at risk of being seen as trying to be better than others, or the worst thing you could be, morally prescriptive. Plus, after 2016, there was a fascist on the loose. Metaphysics, values—these were impossible in Trump’s America, and it was best not to betray one’s privilege by trying to discuss them.

In a course called “Diversity and the Classical Western Tradition” (at the time I had no clue “diversity” had a political valence), I was introduced to Hesiod, Euripides, Herodotus, Hippocrates, Aristotle, Shakespeare, and the book of Genesis. For a public school student and child of immigrants, these canonical texts were revelatory. They were part of the history of the human condition; not once, as an Iranian American, did I find them distant or Eurocentric. My own parents would’ve given anything to study these texts and others, to enter these ancient dialogues about life; to this day, my father becomes emotional looking at the bookshelves of my college texts I’ve left behind at his home. But the day following the election in 2016, my professor didn’t start his lecture as always—he entered a room of 300 students, sat down on the stage floor, and put his graying head in his hands. I remember thinking he seemed childish, selfish. I did not want to be like him.

Many of the authority figures on campus—the teachers, the chaplain—didn’t want to, or couldn’t, give guidance or even basic classroom instruction during Trump 1.0, so I turned away from the tyranny of the present political moment to the timeless classics: I chose to study ancient Greek. In my third semester, one professor frequently interrupted our close reading of the Iliad’s eighth-century BCE Greek to try to relate the events of Troy to Trump’s latest actions. I came away having read almost none of the Iliad; all I remember, truthfully, is forming half of a tiny audience for one male professor’s personal therapy session.

I was begging to be given values, community, a purpose, a vocation—and found none. Instead my teachers repeated what they’d heard on the news. In due time, by forcefully pursuing what was left of a liberal arts education at a large research university, I met professors who were eager to teach me. My entire life I had been told that conservatives, religious people, and men were monsters, idiots, abusers, or dangerous bigots. The very first conservatives I’d ever met, it turned out, were among the few faculty at my university who took their disciplines seriously on their own terms, at least during Trump’s first term. Whether philosophy, literature, or ancient languages, the few conservative, apolitical, or moderate professors I worked with on campus never asked me where I stood, but how I thought. They saw a young woman, choosing to study the liberal arts on scholarships, and gave me an education.

The most serious poet, and poetry teacher, I met on campus was the former chair of the National Endowment for the Arts under a Republican president; other faculty criticized and dismissed him to me on this account. As the son of Mexican and Italian immigrants raised in working-class Los Angeles, he didn’t worry whether the canon he loved, and discovered by luck like me, was outdated or exclusive. We were part of it, too. His happy half-century-long marriage was the first I’d ever seen up close; I definitely wanted to be like him. He told me how scores of young men who took his general-education course would come to his office hours looking for advice, how many of them didn’t have fathers, and how they felt marginalized and mocked by most of the campus culture. “Jordan Peterson realized this before anyone,” he quipped.

Just a day after the end of NatCon, a mile down Massachusetts Avenue, and a day before the July assassination attempt, I attended a different conference: Liberalism for the 21st Century. Scheduled the same week as NatCon and promising to counter its “illiberal ideologies and authoritarian figures,” it was organized by an institution whose magazine is appropriately named The UnPopulist. Walking in, I see a sea of white hair. There are white heads shaking in disapproval on every other panel—staid, unaware, furious. They are defiant, blind to even the most obvious of their blunders, and all the same, clearly deflated.

Many attendees have professional reasons to be there: I recognize journalists Matt Yglesias, Yascha Mounk, and Jonathan Rauch. During one of the first panels on Friday, the main auditorium is empty and quiet enough that I’m afraid, standing by the refreshments, to pour myself another glass of iced tea, should I draw too much attention.

Early on, I attend a panel on how liberalism can respond to “post-liberal critiques.” Mark Lilla, who I recognize from a book tour to my college campus in 2017, describes well the nature of the fever I’d noticed at NatCon: “historical dramaturgy,” the monolithic references to “modernity,” the indiscriminate attribution of life’s frustrations to “liberalism.” For decades Lilla has chronicled and criticized the philosophical challenges to liberalism with intellectual honesty, and I think of how much more compelling the conference would be if it had taken that writing more seriously.

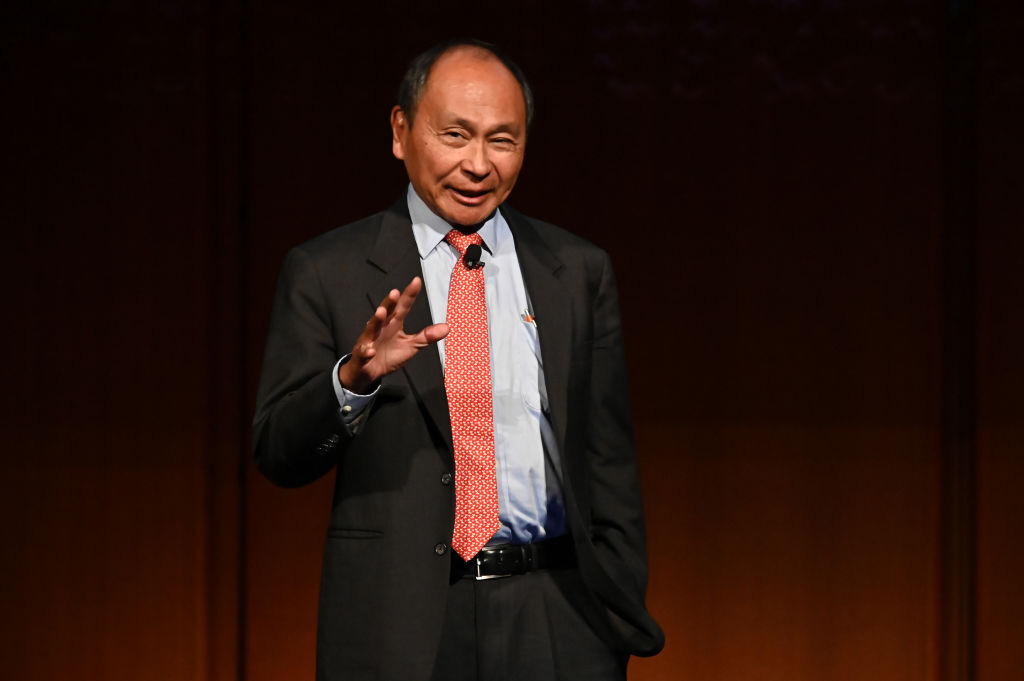

As I wait in the mainstage room in an empty row of chairs, trying to arrange my notes from NatCon for an article that nine days later, once Kamala Harris is appointed party leader and declared “brat,” no editor wants to run, I look forward to seeing another intellectual role model I’d first discovered during college: Francis Fukuyama.

He suddenly appears behind me in that empty room.

Unlike many of the liberalism conference’s “conclave” of liberal intellectuals, journalists, and policymakers, Fukuyama studied classics and comparative literature before getting his PhD in political science. The bipartisan critics of his “End of History?” thesis have waited for three decades, like modern augurists, for a sign from the heavens or history that his end of history is over; but, lacking his disciplinary scope, few, if any, have offered a sophisticated counter-theory of their own. Are any other essays still setting the terms of debate 36 years on?

As I wait for his closing speech, I hope the other conference speakers will at least articulate the philosophical merits of their ideas, not just the material or procedural ones. But no one I hear discusses Locke or Tocqueville or Jacques Maritain or even a liberal internationalist like Charles Malik; the centuries of political activism inspired by liberalism’s focus on individual rights, equality, and human dignity are meaningfully addressed in only one breakout session. Speakers look instead to statistics while name-checking scapegoats like “misinformation.” After eight years of losing ground among a disenchanted global electorate, panel after panel discusses the sociological, electoral, and material—but never the intellectual—causes of post-liberal politics. After his panel, I overhear David French telling a huddle of rapt listeners that social science could entirely explain post-liberalism: The science says the more isolated people are, the more likely they are to be attracted to illiberal ideas. His prescription for combating populism is “more thick friendships.”

After much describing and much decrying, it is finally Fukuyama’s turn to speak. “Many people read the title of my book, but they didn’t actually read the book,” Fukuyama says, referring to his The End of History and the Last Man. These nonreaders, he continues, ignore the cautionary tale of Nietzsche’s “last man”: “a human being that has no aspirations because their material needs are satisfied.” But, still, the “last man,” freed from struggle, wants more: “Human beings have a third part of their psychology, which the Greeks called thymos. This is pride, or spiritedness, or the desire to be recognized for outstanding virtue.”

Rather than resorting to facile social science, Fukuyama grounds his talk in a theory about who human beings are, and what they long for. I doubt Fukuyama thinks much about the National Conservatives, but as he speaks I remember the young men I had met that summer. Trump’s movement and NatCon seem tailored to what they longed for: not to be the last men in politics, but rather the first men to participate in a political future worthy of their heroic aspirations.

The mood at the liberalism conference, and the position of those athwart post-liberal “progress,” is well summed up by a young man, one of the few in attendance, seated directly in front of me as Fukuyama closes. As we applaud liberalism’s most robust defense, he jokes loudly to his friend, “Yeah!!! Woo-hoo! What are we going to do?!” The NatCons may not know exactly who they are—economic leftists who hate leftism, right-wing progressives who hate progress, or moral traditionalists who praise the male libido—but they know what they’re doing. They have a vocation. Does anyone else?

For more on the rise of young conservatives, read Suzy Weiss and Josh Code on the big question: “Is It Cool to Be Right-Wing Now?”

Mana Afsari is a writer based in Washington, DC.

A version of this essay was first published by The Point.