Welcome back to Douglas Murray’s Sunday column, where he presents passages from great writers he has committed to memory—and explains why you should, too. If you want to listen to Douglas read this week’s work, Rainer Maria Rilke’s “Duino Elegies,” click below.

There are a number of questions we will have to address at some point, one of which is what to do with poetry written in languages other than English?

I started this series by describing how a Russian poet could, through translation, match the eloquence of the greatest poet in the English language. But in general, what should our attitude be toward poetry in translation?

With the exception of a few translations by a very few masters, most poetry loses something when converted to a different language. Or, to put it another way, it is almost impossible to convey the meaning, the meter, and the rhyme (if there is rhyme). In general, something has to give.

For instance, one of the great and earliest works of world literature is the Epic of Gilgamesh, which predates the Old Testament, and comes with its own flood narrative and search for immortality. It is a tremendous work, and it received a tremendous translation by the poet Stephen Mitchell. But while I often find myself referring to it, I can never retain chunks of it by heart.

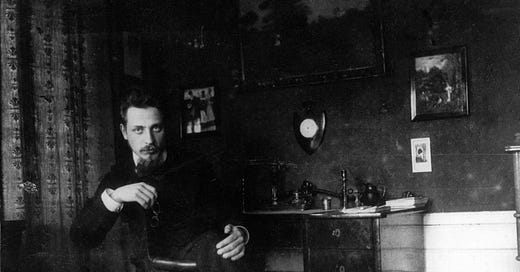

Yet, there are too many great poets in languages other than English, and I refuse to give up on trying to remember them by heart just because I am not fluent in their language. Foremost among these, perhaps, is Rainer Maria Rilke.

Born in 1875 in what was soon to be the ruins of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Rilke was among the most sensitively attuned beings of his age. His work bursts with phrases and insights that are enough to change your life. Sometimes he actually tells you to do just that; other times he gets someone or something else to do the instructing.

In his sonnet “Archaic Torso of Apollo,” the poet meditates on the transformative feeling that can suddenly strike you when you see something—especially something ancient—of great beauty. Rilke is not just an aesthete, or a lover of art. He has the feeling that the work of art is trying to tell us something. But what? Rilke wreaths around the subject as around the artwork and concludes with a line that hits you in a way that only a great truth can: Du mußt dein Leben ändern. “You must change your life.”

Rilke stayed on this earth until 1926. It was not a great time for someone of his sensibilities to be alive. There were many signs Europe was going mad in the run-up to 1914, but one small sign it had lost its head was what the writer Stefan Zweig witnessed one day in that year, which he recalled in his book, The World of Yesterday, perhaps the greatest memoir of the twentieth century.