The Free Press

I’ve always had problems envisioning the underworld. Sulfurous flames belching up from gloomy caverns don’t trigger existential terror in me. This may be because I grew up in Minnesota, where, for over half the year, fire is inviting, cozy, not forbidding.

But even detailed scenes of suffering in hell have always fallen short, for me, of their awful equivalents on Earth: Real war and real famine horrify me more than paintings of the damned devouring their own arms. Literary evocations of hell, which focus on its prisoners’ inner states—I’m thinking here of Virgil’s Aeneid and Dante’s Inferno—affect me more deeply, but once again the miseries they speak of are also available in life. The only distinctively hellish thing about these torments is that they are said to persist for all eternity. Eternity, which, perhaps you won’t be surprised to learn, I also have trouble imagining.

All of this changed for me the other day when I came across a brief animated video. It struck me, at last, with authentic spiritual dread.

The video was a creation of DALL-E, a new artificial intelligence app from the wizards at OpenAI, which is said to represent a breakthrough in the production of machine-made art. You type in a verbal description of an image—“a tarantula wearing a green scarf,” say—and out of the digital void arrives a picture which reflects your specifications. If you’d like, you can tinker with the image the way you might customize a frozen pizza: You can tell the A.I. to render the tarantula in the style of a cubist drawing or a vintage photograph or a Soviet propaganda poster. (How all this works at a computing level I’ll explain in a moment, or I’ll try.) But when I saw the 30-second video, all I knew was foreboding.

The video showed a young woman with long, dark hair standing in a photorealistic garden, her right palm open and turned up. The gesture had a ritualistic quality, as though the woman were a priestess. Above the hand a rock-like object floated, spinning, bobbing and shapeshifting in a spooky way. The camera—or rather the artificial gaze which lent the scene perspective—zoomed in toward the woman’s face and body as she focused on the floating rock. She and the orb-like stone seemed magically bonded, engaged in a creepy telepathic dance.

But the scene’s main attraction was the woman’s clothing. In a liquid, writhing manner, a series of outfits appeared on her body, melted, and were replaced. The transformations occurred too rapidly for me to count (there were dozens) and the spectacle offered the observer no resting places, like a paragraph without punctuation marks. The progression, the sequence, felt mentally punishing, its randomness trembling on the verge of order but eluding the sense-making instinct of the viewer. It was smooth and luscious visual gibberish.

The tweet which framed the loathsome video asserted that “AI will disrupt the fashion industry; DALL.E generates hundreds of outfit options.”

I couldn’t assess this claim, since the only disruption the video caused in me occurred at a more primal level.

After turning it off, I examined further examples of A.I. “art,” both to see if they had the same effect on me and to determine if it was “art” at all.

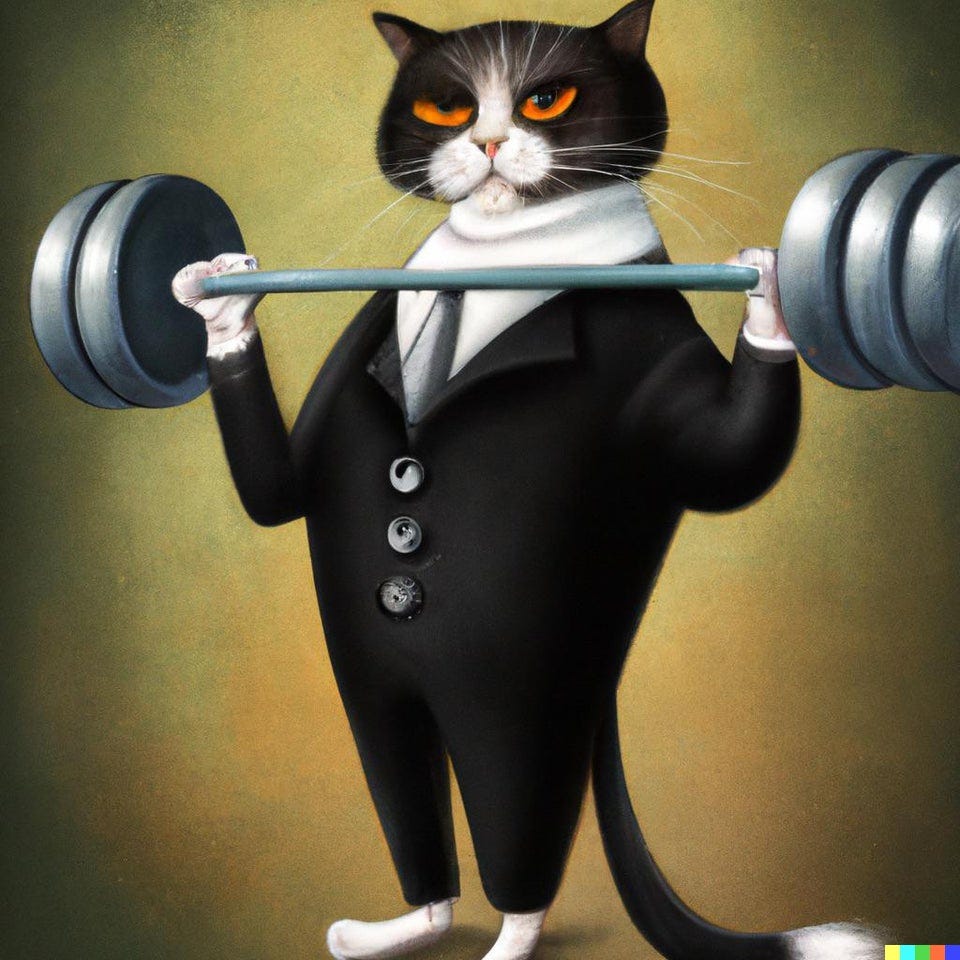

I came across a cat dressed in a tuxedo lifting weights in the style of Van Gogh:

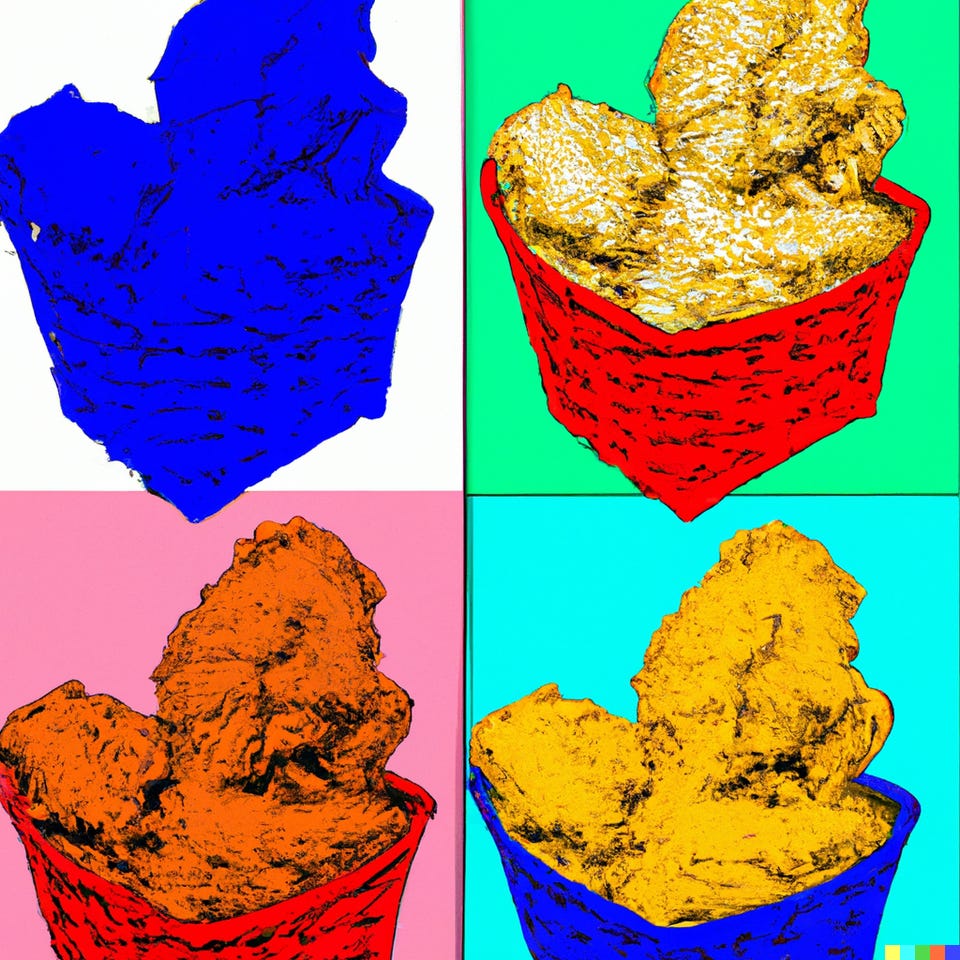

And chicken tenders in the style of Andy Warhol:

And a child playing an electric guitar in the style of Hieronymus Bosch:

I’d read that many smart people believed that this sort of thing was art. In an digital art contest at the Colorado State Fair, the judges had awarded the blue ribbon to an A.I.-generated image.

Before I discuss my own judgments of DALL-E—the name, by the way, is a portmanteau of the Pixar film WALL-E and the artist Salvador Dalí—it’s important to review how it works. DALL-E relies on computerized brute strength. In this case, it amasses tons of images—hundreds of millions, my research revealed—and extracts certain patterns from the vast sample, which it generalizes into rules and formulas. For example, DALL-E has learned what sort of pictures tend to be thought of as cute by human beings. Ask its interface for a “cute pink moon,” and it may devise a moon with big round eyes, long curving lashes, and elfin ears, perhaps.

This approach is ingenious— artificial art!—but is it a paradigm-breaking leap forward, or a massive regurgitation of past achievements? Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, told the New Yorker in July: “There was this belief that creativity is this deeply special, only-human thing.” Was is the operative word.

DALL-E depends on art already made, on photos already taken, aesthetic assumptions statistically derived, and a language—our language—formed over the centuries by acts of communication innumerable about whose nature the great machine knows nothing. It’s largely a cultural-mining operation with a clever assembly line on top. It’s perhaps no coincidence that its name refers to a famous practitioner of surrealism whose work was distinctively suited to reproductions (and look alike variations) on a singularly large scale.

I’ve witnessed this trick before.

When I was a kid in the 1970s, the mall where I shopped for back-to-school clothes hosted a man with a Kimball “Spinet” organ who offered demonstrations to passersby. He got me every time. I couldn’t play the piano, but making music on the Kimball didn’t require such skills. All one had to do was hold the keys down and out came a beat (I usually chose “salsa”) and everything else that goes into making music. The muse, if there were one, was trapped inside the organ like a contortionist curled up in a safe. My button pushing didn’t let her do much, but the salesman was more proficient. The proportion of input to output startled me, but was this music I was hearing? When I observed the salesman’s face, it lacked the odd, strained expressions I was used to when watching pianists on TV, or even organists at church. It registered only mild self-contentment. The Kimball corporation, personified.

I pored over examples of DALL-E’s work, or that of its users. Suspecting that my knowledge of their origins might prejudice me against them in some way, I pretended the pictures had been done by hand, or at least from scratch. Fantasy and sci-fi motifs predominated. Lots of centaurs, ringed planets, and towering white cities overflown by diaphanous winged somethings. I’d read that DALL-E, like most institutions nowadays—particularly of the high-tech sort—has all kinds of rules against courting social controversy, against provoking “hate” and so on. Fantasy scenes and figures help you dodge that, as do space and alien motifs. If other dimensions don’t exist, humans will surely invent them, I concluded, if only to sidestep conflicts raging in this one. (In a Pandora’s box decision, this past week DALL-E announced that it is now allowing users to play with images of their own faces and those of other real human beings. The narcissistic possibilities are endless—what would I like if I were thinner? with bangs?—and the potential for derision of others is unlimited. These funhouse novelty images will grow tiresome eventually, but it may take a while.)

These vividly detailed, far-out images you’ll see when you look up DALL-E are considered by those who fancy the mode incredibly “imaginative,” but they lack intellectual risk. I find them cowardly. Yes, the instructions behind them were probably intricate, exploiting DALL-E’s capacities to the full (“a fallen angel fights a shark on Neptune while a new civilization dawns around them”), but performing complicated feats for their own sake is what jugglers do.

Whatever it is that artists do—and have been doing for all of history minus a few months or years now—they do it under threat. The threats of incomprehension, disgrace, obscurity, political reprisal, loss of love, and even the threats of wealth and fame, which are hazards of their own. But the basic, abiding threat is loss of faith.

As a writer, I face the demon of despair with every blank page, and many full ones, too, when I read what I’ve written and feel it could be better, if only I were able to make it so. A.I. knows nothing of these dramas. It compiles, sifts, and analyzes, then finally executes. But it doesn’t dare. It takes no risks. Only humans, our vulnerable species, can.

Of the hundreds of millions of pictures DALL-E has toyed with, a vanishingly small percentage are art, or were ever considered art, and what might make them art it certainly can’t divine. It knows what people think is “cute,” but even in this it relies on changing tastes and the ambiguity of language. It seeks to solve a thousand mysteries without inhabiting the essential mystery, as only mortal beings do. (Why am I here and what happens once I’m not?) Forever separate from consequence and meaning, reaching, eternally reaching, yet never grasping, it is both a picture of damnation and a tool for producing more such pictures, ad nauseam. It will surely become more ingenious and proficient in its mimicry, to the point of completely disguising its machinations through extrapolation and rearrangement. But the effects will only fool the eyes. The mind’s eye watches from a deeper place, intuitive and ancient, and it will bear queasy witness to the truth that artificial art is merely that.

Walter Kirn’s last essay for us was about the holy anarchy of fun. If you appreciate pieces like this one, please subscribe today:

Question: does this program only produce digital files? If so, then it’s missing an essential element in painting… brush strokes. The quality of those on a canvas are an important element in art. Real art

AI exists in an abstract, disembodied world. We often do that, too: look at Putin, or Liz Truss, who naively expect the world to conform to their schemata. But then, so do scientists, who as a group tend to be right. Artists generally do not put stock in abstract schemas; the very point of their work is to find an opening no one else has noticed and to make something unpredictable with it. If art doesn't surprise it cannot delight. Approaching art always means not seeing, being mystified, have to solve some kind of puzzle, which if done lifts you to a higher, more demanding mystification. The unknowing never departs from art; at the very least, it consists of how we have changed in the time since we first encountered a work. AI is never going to tell us who we are, and for the same reason it cannot create the species of communication we call art.