The Free Press

Editor’s note: A previous version of this story misstated that a majority of grandkids in West Virginia, and in Lincoln County, are being raised by their grandparents. This was based upon a misreading of Census data. In fact, it is a majority of grandparents living with their grandchildren who are also responsible for their care. The Free Press regrets the error.

In a one-story house at the bottom of a gully in Branchland, West Virginia, Debbie Vance is sitting in her recliner, watching a rerun of Mama’s Family, when her two grandchildren burst through the front door. Her 15-year-old grandson, Owen, who Vance says looks “just like his father,” kicks off his tan cowboy boots onto a mat. His sister, Autumn, drops her purple bookbag on the floor and runs to her bedroom, where a miniature dachshund named Bandit has been barking up a storm.

“Oh, Lord,” Vance says, rolling her eyes as Bandit races out of the room and onto her lap.

This is not just a weekend with Grandma. This is every weekday at 4:15 p.m., when a school bus hugs the foothills of the Appalachian mountains to get Autumn and Owen safely back into the arms of their grandmother, a 56-year-old widow who’s been watching the two teens since “basically at birth.”

Their father, Vance explains, is currently “running from the law” after he was caught trying to sell opioids in the parking lot of a doctor’s office. Together, the three of them form one of the tens of thousands of “grandfamilies” rising out of West Virginia’s opioid epidemic. Vance, who became the kids’ legal guardian in 2018, sees her current nuclear unit as a chance to get things right the second time around.

Ever since she could speak, Autumn has called her grandmother “Mamaw.” That’s because her grandma “is more of a mom to me than my actual mom is,” the teen said.

Up until our country’s postwar heyday, it was common for grandparents to live in the family home. Now, it’s usually a sign there’s something amiss—either the grandparents need to be looked after or the kids need better care. Out of the more than two million kids being raised by their grandparents in the U.S., the majority are living with their family elders due to a parent’s drug abuse.

In West Virginia, which has the highest rate of opioid overdose deaths in the nation, half of all grandparents living with their grandchildren are also raising them. But here, in the state’s southwestern Lincoln County, where sleepy towns are tucked into rolling hills, an employee for the local school district estimates that the majority of kids are now being raised by their grandparents.

Sam Quinones, a journalist who’s been covering the opioid epidemic for more than a decade, says the crisis has now been raging for three decades, wreaking havoc across multiple generations. “One generation leads to another, and that leads to another, and that leads to another,” he says.

Quinones calls grandparents the “backstop” to even more suffering in a crisis that has taken more than 800,000 lives nationally since 1999.

“If it weren’t for grandparents stepping up, we’d be in even much worse shape than we are right now,” he told me. “It’s a wonderful thing, but it’s not the natural order of things.”

In an office hidden away in the local elementary school, Sue Burton, 68, runs the local chapter of Healthy Grandfamilies, a statewide educational program for grandparents, which she started in 2017. She tells me she has more than a hundred grandmothers—plus three grandfathers—on her roster, but says “there’s hundreds more out there” who need help. She says even great-grandparents are increasingly raising their great-grandchildren in the county.

The average grandparent Burton works with is a 56-year-old widow raising three grandkids and living on less than $19,000 a year. In the two days we spent together, I watched her pay off a grandmother’s $375.35 utility bill, order graduation gowns for two kids who couldn’t afford them, and drop off groceries to a grandmother who told me she just “couldn’t seem to get ahead.”

“These grandfamilies love their grandkids so much that they’re going to take care of them regardless of what it takes physically, mentally, and financially. Even if it’s the last dime they have.”

Burton started raising two of her own grandsons after their mother—her daughter-in-law—slipped into drug addiction, and her son, who works nights, needed her help. “I ate a lot of peanut butter sandwiches just so they could have money to go to a ballgame,” she says about her grandsons, who she calls “my boys.” “There were many, many times that I was like, ‘Do I pay my utilities or do I buy some food?’ ”

But all the pain, she says, was “worth the struggle.” Every night, she and her two grandsons, a college senior and a 21-year-old crane inspector, end up in a group text.

“We text each other, ‘I love you, and I hope you have a good day tomorrow.’ ”

Last summer, she says, her eldest grandson thanked her for taking them in.

“He said, ‘Mamaw, I’m so thankful for you—I’m so glad you raised me, and I wouldn’t change anything. Because if I was living with Mom, I’d probably be on drugs myself.’ ”

Every afternoon you can find Felicia Cook, 60, in the same place: perched in her rocking chair on her front porch in West Hamlin, waiting for the school bus to round the corner. In 2017, Cook said she noticed something “different” about her daughter and her ex–son-in-law. “Something changed,” she said. “They became two people I didn’t know.”

Then one day in 2019, her eldest granddaughter, Jada, showed up on her doorstep with three suitcases. “I’m staying with you, Mamaw,” Jada said. “I can’t deal with it up there no more.”

That’s when Jada, 17, and her younger sister, Tori, 12, moved in. About a year later, Cook lost her husband, “the only man I was ever with,” after he fell off a ladder while installing fiber-optic cable at his job.

Suddenly, Cook was a single, middle-aged grandmother on disability, but she couldn’t give up her grandkids because “that way I know where they’re at. And what’s been done to them.”

“I couldn’t stand not knowing where they were. I’m sorry,” she adds, choking back a sob, “it’s been a long, hard road. Got a long road ahead of me.

“It’s been me by myself, just trying to do the best I can. Keep them safe, give them an education, get them ready for the big world out there.”

Jada calls her Mamaw’s home, which Cook built with her husband nearly forty years ago, a “safe space.” She tells me that Cook runs a wood burner in the winter, is “always cooking something,” and plays rummy with her for hours each night.

“I come and give her a kiss every night,” says Jada.

For the past few years, Jada has been seeing a therapist to help manage her anxiety—a condition she says she developed as a kid, watching her parents fight. Her near-constant panic attacks are also why she decided to finish her high school courses online. Last May she graduated a year early, and ever since, she’s been trying to save up money for a place of her own, maybe college.

“I’m scared. I don’t know how I’m going to do,” she says about a future without Mamaw by her side.

But her real goal is to “repay her somehow, one day.” Then she turns to look at her grandmother: “I will, I’ll take care of you.”

When I met Kim Tomblin, a former hairdresser raising two of her grandkids, for lunch at an Italian spot on the main drag of Hamlin, she spent the first hour wondering what happened to her daughter. She told me she used to be a “thoughtful girl with a kind soul”—the kind of daughter who once bought a carrot cake, her mother’s favorite, for her birthday. But then she says she got hooked on pills.

“Now I feel like her soul is missing,” she tells me, staring down at her meatball sub.

She says the whole town, which she calls “shell-shocked,” is full of stories like hers. But it doesn’t occur to her to blame anyone until I ask if she’s angry with the pharmaceutical companies. Then she drops her sandwich back into its plastic basket.

“Furious,” she says, flicking her eyes up to meet mine. “They knew what they were doing, and they didn’t care.”

Many of the largest companies that profited from the opioid epidemic have never admitted wrongdoing in their role hooking hundreds of thousands of Americans on prescription opioids. Even in 2021, when Johnson & Johnson, along with three major distributors, agreed to pay state and local governments $26 billion for flooding their towns with highly addictive drugs, the pharmaceutical giant maintained its actions were “appropriate and responsible.” And while Purdue Pharmaceuticals, the corporate behemoth behind OxyContin, pleaded guilty in an $8 billion settlement, the family behind the empire—the Sacklers—has never admitted fault.

In 2020, when appearing before the U.S. House Oversight Committee, Kathe Sackler, a former board member for Purdue, pivoted when she was asked to apologize for the impact of the drug her company made. “There’s nothing that I can find that I would have done differently,” she told the panel. Directly after, her cousin, David Sackler, chimed in: “I conducted myself legally and ethically.”

West Virginia is expected to receive around $1 billion of the compensation payouts from pharma companies being distributed across the nation—the highest per capita amount of any state—to account for its sky-high overdose death rate. But the mayor says only about $47,000—or 0.0703 percent—of that will trickle down to Hamlin.

Hamlin mayor David Adkins, who’s known by everyone in town as Flimsy, his childhood nickname, says “that kind of money is a slap in the face because of all the money that pharmaceutical companies made on opioids all these years.”

Adkins wishes the state had put more cash back in the hands of towns like Hamlin. Although states like North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Ohio all distributed the majority of their funds to local governments, West Virginia gave just 24.5 percent of its settlement cash to local municipalities. The rest goes to the West Virginia First Foundation, a state-run nonprofit still determining its guidelines for distributing grants.

Meanwhile, the mayor has to figure out how to heal his entire community with less than $50,000. Looking out his office window, he points to the lot next door, currently filled with overgrown grass and rusting pipes.

“We’re thinking about building a splash park for the kids,” he says, shrugging.

Adkins used to be a lifelong Democrat. Or “conservative Democrat,” he says—he never cared much for all the social justice talk. But then President Barack Obama began his “war on coal,” as critics called his push to cut carbon emissions. By the end of his second term, coal production had dropped by 40 percent in West Virginia, axing eight thousand jobs along with it.

“It killed the state,” Adkins tells me. “It killed us.”

Now, what’s left of Hamlin, where Adkins has been the mayor since 2014, is a hollowed-out main street with just a few businesses: a 7-Eleven, a funeral home, a hospice care service, and a post office. He no longer believes the Democratic Party cares about the working class.

“They say they care about us to get voters but it’s just a lie,” says Adkins. “My party left me—I didn’t leave it. It left me.”

In November, Adkins will cast his vote for former president Donald Trump, who he said he first voted for in 2016 as “the best of the two evils” but later came to like. When I asked if he feels abandoned by national leaders, he doesn’t miss a beat—“yes.”

“Especially Lincoln County—I have a hard time getting anything for Lincoln County because why would people send money here? The cold, hard fact is there’s nothing here.”

In the last two presidential elections, Trump won every county in West Virginia. But while some of his support statewide has stayed stagnant, hovering around 69 percent in both elections, Trump picked up steam in Lincoln County, with his 75 percent win in 2016 jumping to 77 percent in 2020. Debbie Vance, the grandmother whose son is on the lam, says she’s planning to vote for Trump a third time this November. When I ask why, she tells me about the $200 clothing voucher the state gives her every year for each of her grandchildren.

“What can you get kids for $200?” she wants to know. “They don’t want to go to school in clothes from a rummage sale, or whatever. They want to look as decent as the kids who’ve got plenty of money.”

Vance, who says she lives on a combination of supplemental security income, disability, and a widow’s pension, is sick of seeing Biden send money abroad to countries like Ukraine and Israel.

“I don’t feel like he’s done things to help the American people.”

The year 2000 is when Kim Tomblin noticed that something was changing about Lincoln County. That year, she’d just opened up her hair salon in West Hamlin, when she heard two teenagers in the waiting area whispering about how to snort pills.

“What do you get out of that?” she remembers asking one of the boys when he sat down in her chair for a haircut. “I’m not judging you—I’m just curious.”

He smirked and replied, “It’s like drinking a whole case of beer.”

That was the first time she ever heard about anyone doing drugs harder than marijuana or liquor, she said. But after that, she kept seeing signs of it everywhere. She once walked into a woman shooting up in the bathroom of a local gas station. And when she went on to manage a convenience store, she says she lost count of how many times she heard about one of her customers overdosing.

“Just within a span of a couple of years, I started seeing people just go downhill,” she told me.

Then Tomblin, who said she “never expected” to see anyone do heroin in her life, suspected her own daughter was doing just that. On a summer night in 2006, something told her to check on her 18-month-old granddaughter, Star. The night before, she’d seen cars outside her daughter’s house, and figured there was drinking going on inside. She thought she’d help her daughter out by babysitting so she “could recover from a hangover or whatever.”

When she opened the front door, she found her daughter passed out on the couch. Tomblin remembers shouting her name. Her daughter didn’t flinch, though “she was still breathing.” A few feet away Star stared up at her with big brown eyes and a “real big smile.”

“She lit up and lifted her hands to me,” Tomblin told me. “So, I gave her a bath, got a bag of clothes and toys—and I just took her home.”

That’s the day she became her granddaughter’s main caretaker, followed by her younger brother, Reese. Today, Star is about a year away from graduating high school with her eyes on becoming a mortician. It’s not how Tomblin expected to spend her golden years—raising yet more kids—but she says she wanted to intervene before the state did it first.

“Was it my plan? No, but I knew they would come to no harm” in her care, she says. “They will never go hungry—because they knew what hungry was.”

She says that even though her daughter has stolen from her and lied to her face, she still loves her “fiercely.”

“For her, and for these kids, I’m going to make sure they’re taken care of,” she says, her eyes watering.

Then she straightens up and exhales.

“I haven’t got much money, but I want them to have dreams and goals. I wanted that just as much for my own daughter, too.”

Star, who speaks partially hidden behind her long, dark hair, tells me that sometimes, when her parents were faring better, they’d briefly take her back. When that happened, she said she would take one of her grandmother’s pillows to sleep with.

“I feel like I’ve always lived with my grandmother, even if she wasn’t there,” says Star, 19. “It’s always there. You ever had someone who’s always going to be there? No matter what? She was just a real pillar of support for me.”

When I ask her what she wants out of life, she replies with a single word: “stable.”

She clears her throat.

“I’m just focused on survival. On being content. I don’t think I’ve ever had the motivation to be extraordinary. I just really want something stable.”

Olivia Reingold spent a week in rural West Virginia reporting this story—stopping into diners, speaking with local preachers, and venturing down gravel roads to reach families who had never spoken with journalists before. Stories like these take resources; reaching Lincoln County alone requires a full day of travel from New York.

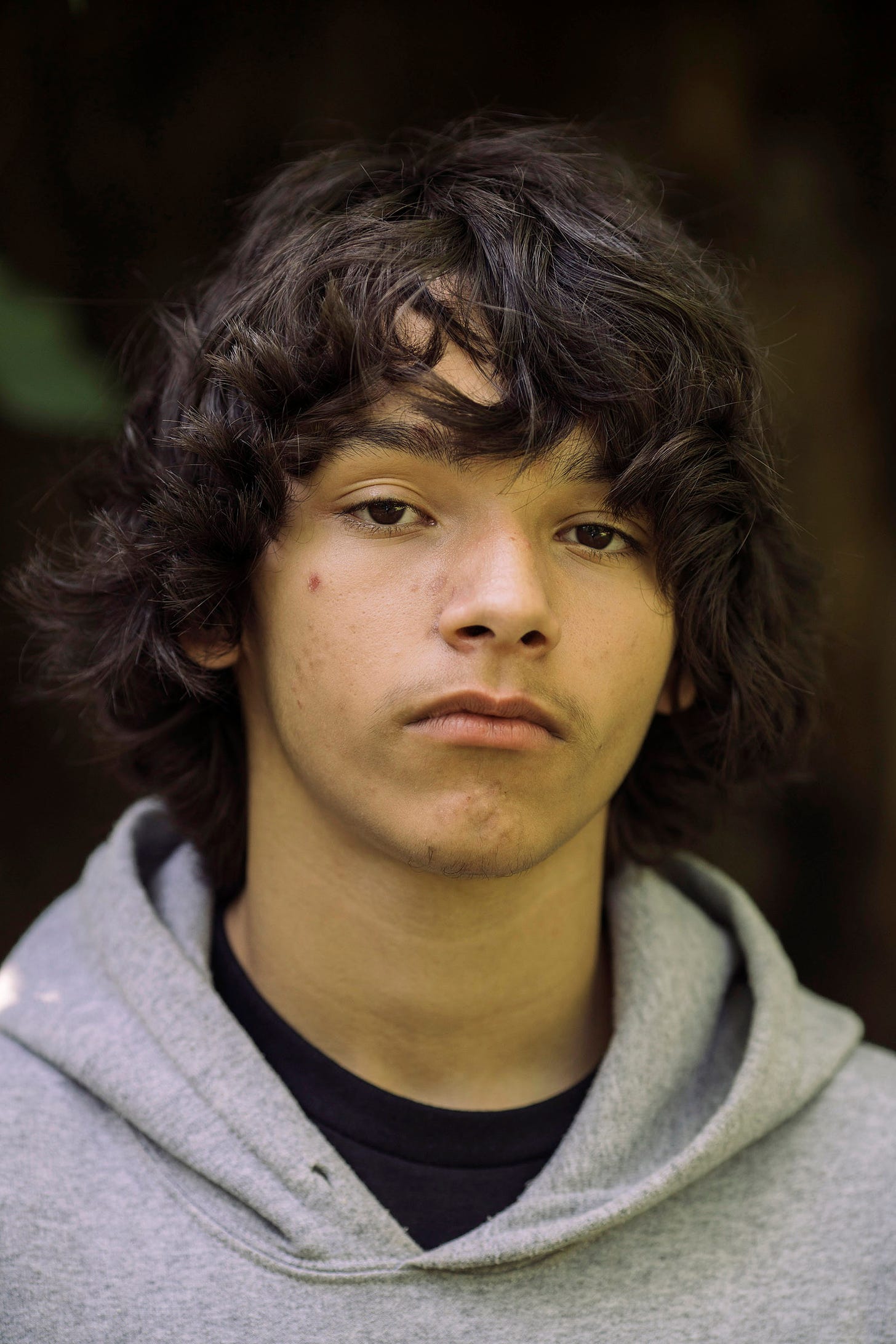

At The Free Press, we believe in the power of on-the-ground reporting. While our peers are increasingly gathering information by Zoom, we’re pounding the pavement, going out of our way to meet people who are often ignored by the media. You’ll see those Americans in today’s striking photos, which were taken by Andrew Spear, an Ohio-based Free Presser.

If you believe in our work and want to support more of our reporting from overlooked corners of America, become a Free Press subscriber today.

More than $26 billion in blood money, we deserves justice. Those who pushed drugs into these communities - looked the other way when profits got too high, and directed it all - have a lot to answer for. It's a cryin' shame. May the next generation think twice about their products.

Thank you for your direct and compassionate report of a story unfolding in families all over the country (mine included). So much of what I've read on this subject is just poverty/addiction porn, and I appreciate your deft handling of a difficult and emotional issue for so many people. If anyone thinks this can't happen in their family, they should think again.