The Free Press

Emily Yoffe, senior editor at The Free Press, here. Last year while scrolling on X, I came across a post that caught my attention. It was a short clip of an interview with Marshall McLuhan, a Canadian philosopher and English professor. I had vague memories of McLuhan—who died in 1980—as a semi-famous intellectual of his day. The young writer who posted the clip, Benjamin Carlson, promised it was “one of the most mind-bending riffs on identity in the digital age I’ve ever heard.”

As I listened, I got a rush from the prescience of McLuhan’s words. It was as if this man, now more than 40 years dead, was a messenger from the future who had been sent to our past, and now was explaining to us the world we live in today.

I wanted to know more about what McLuhan foresaw, and the fascinating essay below from Benjamin Carlson is the result.

Meanwhile, we at The Free Press started talking about whether there are other McLuhans from the past, people who predicted our current moment. That is, people whose words, work, and life illuminated something essential about the increasingly strange times we find ourselves in today.

That’s how our new limited series, The Prophets, was born. Every Saturday for the next several weeks, we will bring to you an activist, scientist, writer, or thinker who somehow knew what would happen years or decades after their deaths. None of them were right about everything. Indeed, some were significantly wrong about significant things. But they all saw something important coming.

And because every prophet deserves their own brilliant scribe, we asked some of our favorite writers to bring you the stories of our prophets. Many of these writers have been experiencing—and covering—the very issues the prophets predicted.

We hope our new series delights, inspires, and occasionally even infuriates you. Ultimately, though, we think these essays make our times easier to understand—and will help you feel less alone in our crazy, fractured world.

You are reading this essay because Marshall McLuhan, in some sense, planned for it.

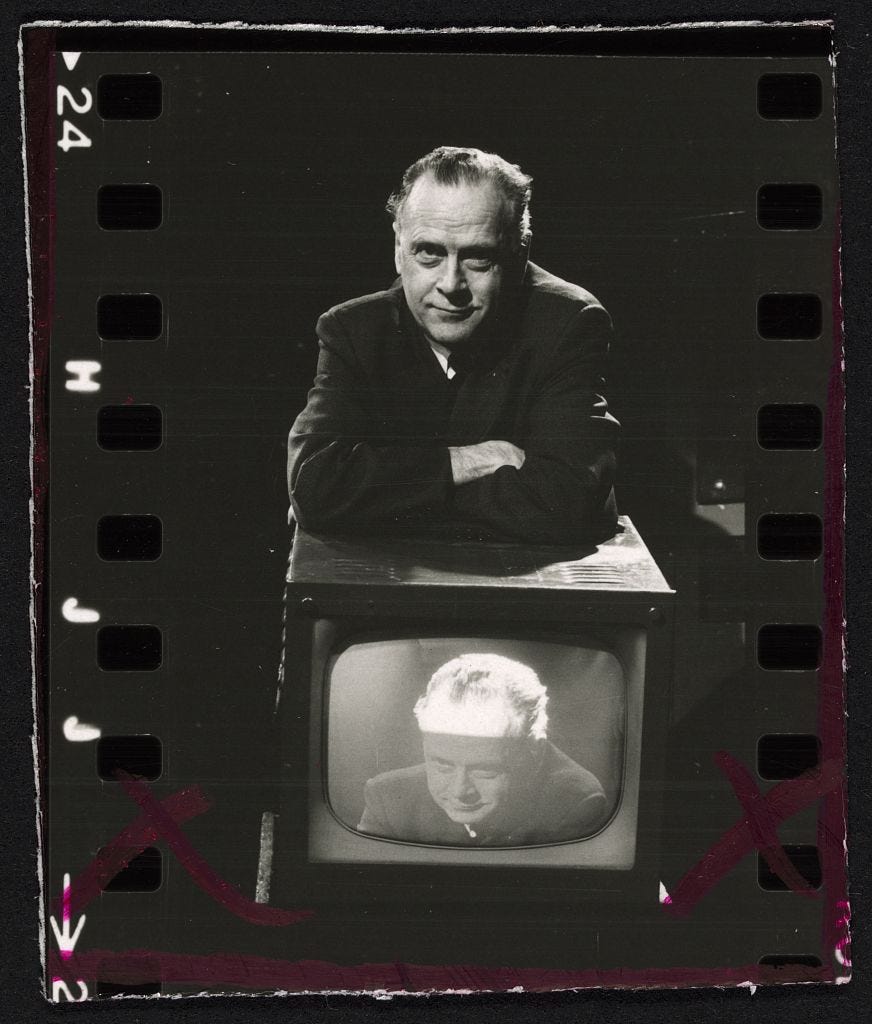

In the mid-1960s, when he exploded onto the American pop-cultural scene—which was also planned; more about this in a moment—he decided to embrace television.

This was not because he was born for TV. He was too “hot” for the medium (in the McLuhanesque sense of being uptight), as he famously said of Richard Nixon about his presidential debate loss to the “cool” John F. Kennedy.

Rather, McLuhan used TV because he, more than anyone of his time, understood how electric technology was transforming society and, even then, had already transformed it.

He knew that whether he liked it or not, TV was where he had to be. His mission was to wake people up—to “needle the somnambulists,” as he put it. (This one phrase gives you a flavor of his style: deadpan and unabashedly esoteric.) If TV was as revolutionary as he understood it to be, his message had to run on TV to have any chance of influencing the present—and being revisited in the future.

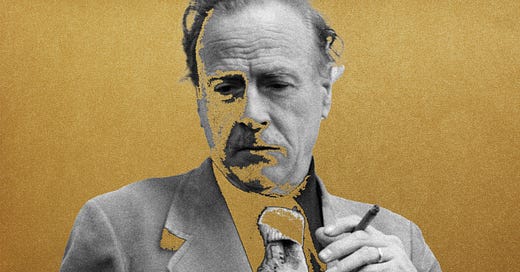

I first stumbled upon Marshall McLuhan a year ago on YouTube. Within a minute or two of watching a clip, I was amazed: here was a man who, in 1977, seemed to be describing the dislocating experience of living in 2023, and he did so with more insight than people living today. That the words were coming from a craggy, mustachioed man in a rumpled suit only enhanced the eerie feeling. Here was a professor-as-prophet. McLuhan says, in part, to his TV host:

Everybody has become porous. They’ve got the light and the messages go right through us. By the way, at this moment we are on the air, and on the air we do not have any physical body. When you’re on the telephone, or on radio, or on TV, you don’t have a physical body. You’re just an image on the air. When you don’t have a physical body you’re a discarnate being. You have a very different relation to the world around you. And this, I think, has been one of the big effects of the electric age. It has deprived people, really, of their private identity. Everybody tends to merge his identity with other people at the speed of light. It’s called being mass man.

I shared the clip on Twitter and it went viral with more than 6 million views —including both of Twitter’s father figures, Jack Dorsey and Elon Musk—suggesting I was not alone in my reaction.

Something about Marshall McLuhan has struck a chord—has resonance, as he liked to say. (He believed the electric age was fundamentally acoustic; a confusing concept, but roughly meaning that everything occurs simultaneously.) The long-deceased Canadian scholar—he died in 1980—who first blew people’s minds in the mid-1960s, is blowing people’s minds again.

This is not because he predicted specific devices or apps, but because he understood, with a poet’s intuition, the effects of the electronic age on human psychology.

He did not get everything right. But those things he did get right stemmed from his deep insight into the shift from the mechanical age (of which print was a part) to the electronic era, whose implications are still unfolding.

Trained as a literary scholar, Marshall McLuhan was an unlikely prophet of technological change. He was an English literature professor with the tall, rigid, imposing, yet vaguely shabby air of a Scottish laird (to borrow journalist Tom Wolfe’s affectionate phrase for him).

He was born as Herbert Marshall McLuhan in 1911 in western Canada to a father who had a real estate business and a mother who became a popular performer of “elocution”—the now defunct art of public oratory. He enrolled in the University of Manitoba and, in his first year, studied mechanical engineering. He soon switched to English literature.

Winning a scholarship to Cambridge for his PhD, he wrote a dissertation on Elizabethan poetry. While in England, he had two major influences: scholars who studied popular culture of the day, including comic strips and cartoons, and converts to Catholicism such as G.K. Chesterton and Evelyn Waugh. In 1937, McLuhan himself converted.

As a young professor of English at St. Michael’s, the Catholic college within the University of Toronto, where he chose to spend his career, McLuhan gained a reputation as a literary critic who analyzed the formal innovations of Modernist poets: Yeats, Eliot, Joyce, Pound.

McLuhan could have continued on this track. But, exposed to other influences (particularly Harold Innis, an economist and communications theorist at the University of Toronto, and Eric Havelock, a classicist and author of Preface to Plato), he decided to take his literary tools and use them to analyze technology itself.

Instead of staying in his track, he blew it up.

The charge for this explosion was a 33-chapter book published in 1964, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. In this esoteric, electric work, he laid out a theory of technological change encapsulated in the often-misunderstood phrase, “the medium is the message.” By this McLuhan meant that the most important effects of a new technology are a result of its form, not its content. (When McLuhan speaks of a medium, he means “any extension of ourselves”—whether it be the alphabet, clothing, roads, or satellites.)

In other words: it’s not what’s said on Twitter that matters. It’s that Twitter is part of our world that matters.

We make YouTube, and thereafter, YouTube makes us.

Or as journalist Tom Wolfe, an admirer of McLuhan’s, summarized it: “Nothing people can use electronic media for—no message that anyone, no matter how powerful or persuasive, can deliver—even begins to compare with what new media have done to mankind, neurologically and temperamentally.”

Reading it today, Understanding Media continues to give insights from its dense thickets of theory, quotation, and allusion. (McLuhan is the only author I’ve read who casually quotes Finnegan’s Wake as if it were as familiar to everyone as Tom Sawyer.) You can benefit from dipping in and out, or even simply reading the introduction. There, on the first page, he makes an observation that I think is one of his most important and relevant commentaries for our time: that in an electronic era, we live increasingly outside our bodies and outside physical time. He said:

Today, after more than a century of electric technology, we have extended our central nervous system itself in a global embrace, abolishing both space and time as far as our planet is concerned. Rapidly, we approach the final phase of the extensions of man—the technological simulation of consciousness, when the creative process of knowing will be collectively and corporately extended to the whole of human society, much as we have already extended our senses and our nerves by the various media.

Remember: he wrote this before 1964, decades before the birth of the internet, social media, and artificial intelligence.

In Chapter 32, “Weapons: War of the Icons,” he anticipates a form of meme warfare, where a battle of information and images take the place of most “hot” wars.

And in the last chapter, “Automation: Learning a Living,” he foresees that in a time of automation, “it is not only jobs that disappear, and complex roles that reappear,” but also whole specialized fields in education that vanish. The result, he writes with uncanny prescience, is a blending of work and leisure, the globalization of manufacturing, the monetization of information, a rise in self-employment, and a necessity to repeatedly retrain for skills in a career.

“It is a principal aspect of the electric age that it establishes a global network that has much of the character of our central nervous system,” he writes, thereby “enabling us to react to the world as a whole.”

How did he understand so well what was coming?

As very few did, he saw that the new technologies of the electronic era—from the telegraph to radio, telephone, TV, computers, and now the internet—change us. They make up a new environment, and as any new environment alters an organism, so our technology alters us.

In particular, he believed that new electronic media changed how we use our five senses, which in turn change how we think, feel, and respond—leading to new identities and forms of society.

When Understanding Media was published, it landed with a bang.

One early reader was so impressed he decided the world needed to know Marshall McLuhan.

His name was Howard Luck Gossage. An advertising man known as the “Socrates of San Francisco,” Gossage called Marshall and asked him, “Dr. McLuhan, how would you like to be famous?”

When the Canadian assented, Gossage went to work. He and his friend, a proctologist and amateur ventriloquist named Dr. Gerald Feigen, took $6,000 of their own money, and in 1965, flew McLuhan to New York. There they feted him with society people and journalists—one of them an astute literary chronicler named Tom Wolfe.

In November 1965, Wolfe published an article on McLuhan in the New York Herald Tribune with the Wolfeian headline: “Suppose he is what he sounds like, the most important thinker since Newton, Darwin, Freud, Einstein, Pavlov. What if he is right?”

The article, and Gossage’s campaign, made McLuhan into perhaps the unlikeliest pop culture icon of the late 1960s.

“Marshall McLuhan was the magic ingredient on which this turned,” Andrew McLuhan, Marshall’s grandson, told me. “He was one of the wittiest people alive. His brain was so fast he talked circles around just about anybody.”

Within a few years, McLuhan had appeared on Dick Cavett’s talk show, debated Norman Mailer, served as a guru for corporations including General Motors, and gave rise to a new French term for pop culture, McLuhanisme. And, at the peak of his fame, he made a cameo as himself in Woody Allen’s Annie Hall.

He took his moment in the spotlight to warn that the “global village” (a term he coined) would not be a happy, harmonious place. He said:

Global village is not created by the motor car or even by the airplane. It’s created by instant electronic information movement. The global village is at once as wide as the planet and as small as a little town where everybody is maliciously engaged and poking his nose into everybody else’s business. The global village is a world in which you don’t necessarily have harmony. You have extreme concern with everybody else’s business. And much involvement in everybody else’s life.

Then, as fame tends to do, it gave rise to critics. And the McLuhan moment passed.

This did not end Marshall McLuhan’s work.

His research continued, and he developed a close partnership with his son, Eric McLuhan.

Eric, who lived until 2018, was an often-forgotten presence in the McLuhan legacy. The work of both men is preserved by Eric’s son Andrew McLuhan, who digitizes and presents their ideas on the excellent McLuhan Institute podcast and YouTube channel.

If the first part of Marshall McLuhan’s career was devoted to needling the somnambulists, to wake people to the effects of technology, the second part was devoted to giving people analytical tools they can use to take control of change.

In the book Laws of Media, the McLuhans identified four things they believed all technologies did:

Enhance — to make something possible, or accelerate it

Obsolesce — to make an old thing obsolete

Retrieve — to bring back some feature of an earlier technology

Reverse — to reverse or flip when pushed to an extreme

They turned these laws into a tool they called the tetrad. The tetrad asks four questions of any new medium or technology. The answers to these questions give you a starting point to grasping the possible effects of any new development.

To take one example from Marshall McLuhan’s last book, The Global Village (unfinished before his death, and completed by a collaborator), McLuhan thus analyzed the effects of global networking of media:

What does it enhance? “Instantaneous diverse media transmission on a global basis.”

What does it obsolesce? “Erodes human ability to decode in real time.”

What does it retrieve? “Brings back Tower of Babel: group voice in ether.”

What does it reverse? “Reverses into loss of specialism: worldwide synesthesia.”

Not bad, given that Marshall died at the age of 69 from a stroke in 1980, a full generation before the rise of the social media whose effects he so accurately predicts and describes.

What made Marshall McLuhan so prescient?

Like many astute observers, he was an outsider to his field. As a technologist, he was unusual in at least three ways: an Elizabethan scholar by training, a devout (and private) Catholic, and a man who admitted he was, in his personal opinions, “resolutely opposed” to the changes he foresaw.

But he insisted upon the necessity of understanding even that which he disliked.

“I don’t choose to sit and let the juggernaut roll over me,” he told an interviewer in 1966.

It’s almost eerie to hear him describe, over half a century ago, the functions provided by artificial intelligence tools like ChatGPT. His vision anticipates a world of bespoke information and analysis (some of it hallucinated) that have flooded our world.

When you have a research question, you will not go out and buy a book, he says. Instead:

You will go to the telephone, describe your interests, your needs and your problems. . . . And they at once Xerox with the help of computers from the libraries of the world, all the latest material just for you personally, not as something to be put out on the bookshelf.

McLuhan anticipated that the electronic age would be one of constant change, such that nobody could adapt quickly enough. As a result, people would be plunged into nostalgia, and yearn for their old, solid identities.

He tried to warn everyone but could see that he was not well understood. In interviews, McLuhan sometimes compared himself to Louis Pasteur, the microbiologist, trying to tell humanity that their greatest enemy is all around them.

As he writes in The Global Village, in a rare moment of deviation from his usual neutral tone: “What may emerge as the most important insight of the twenty-first century is that man was not designed to live at the speed of light.”

His aim was to empower people to see what was happening so they might exercise choice over the uses of technology in their lives.

“He understood he was never going to accomplish this task in the classroom in the university,” Andrew McLuhan said to me.

“He knew the only way to do it was to meet people where they were. In his day, it was popular TV. In ours, it’s YouTube and elsewhere. He’s been gone four decades and he’s still working.”

Benjamin Carlson is a writer, media strategist, and author of the newsletter Carlson Letter. Our second prophet will be in your inbox next Saturday morning.

To support more of our work, become a Free Press subscriber today:

O. M. G.

You help me comprehend but unfortunately not make sense of how my life of intergrating into my sense of right and wrong Brown vs Board of Education, Lincoln’s Emancipation Declaration, and our instinctual tribalism[ Aparteid ] has led our nation to this sanctimonious state of intolerance of those who disagree. I will not let sadness haunt my remaining years. In the words of Jewel “only kindness matters” to which I would add respect must be part of the kindness we show others