Welcome back to The Prophets, our Saturday series about fascinating people from the past who foresaw our current moment. Last week, Louise Perry wrote about Andrea Dworkin, the feminist who imagined—with uncanny clarity—how our world would be shaped by online pornography.

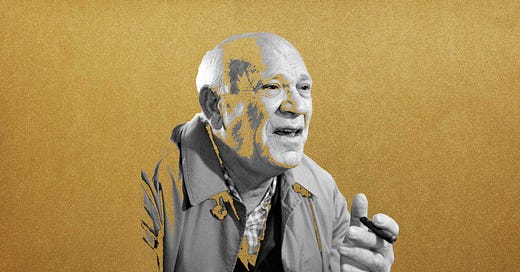

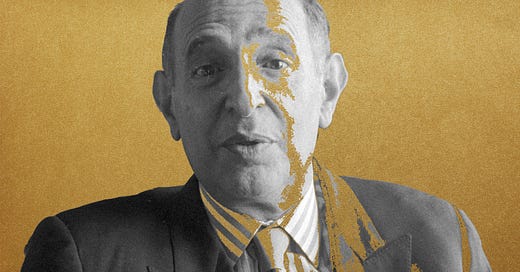

Today, Rob Henderson celebrates Eric Hoffer, the blue-collar philosopher who explained how mass movements form, and warned about a society ruled by elites.

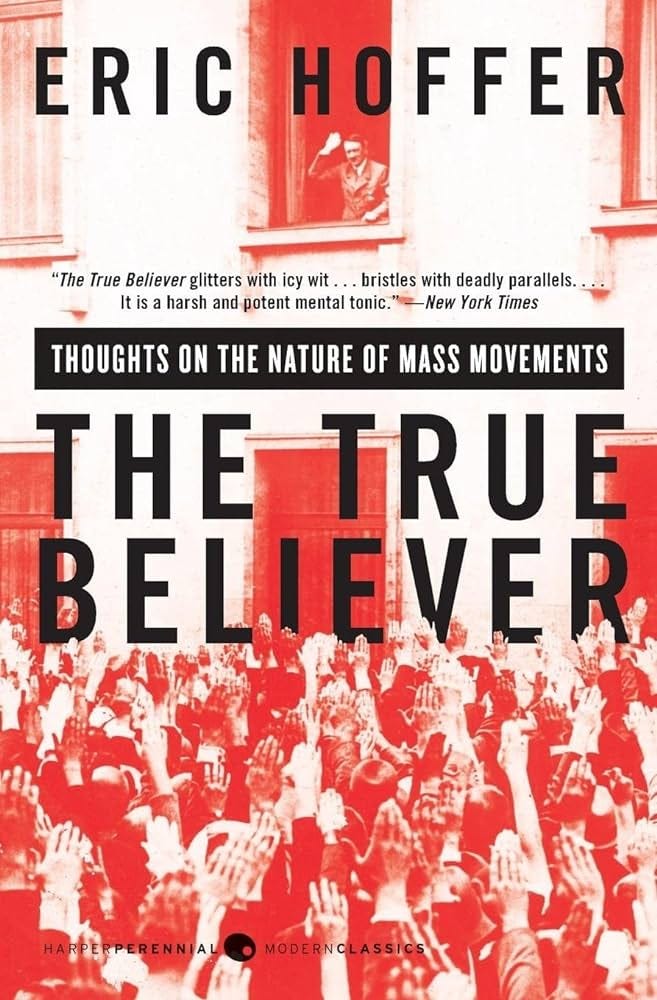

For more than 70 years, a slender volume written by a dockworker who died in 1983 has been handed around by presidents, would-be presidents, journalists, students, and more as a guide—decade after decade—to epochal and baffling events.

Published in 1951 in the shadow of World War II and the rise of the Soviet Union, Eric Hoffer’s The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements became one of President Dwight Eisenhower’s favorite books. As the former Supreme Allied Commander of European forces during World War II, Eisenhower saw firsthand the rise of mass movements and how they turn destructive. During one of the nation’s first televised presidential press conferences, Ike cited the book, turning it into a bestseller.

Hoffer, often called “the longshoreman philosopher,” was admired across the political aisle. In 1967 he was an overnight guest of President Lyndon Johnson at the White House. In 1983, President Ronald Reagan awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Years after Hoffer’s death, his book was rushed back into print and sold briskly when, in the new millennium, people turned to The True Believer to explain the attacks of 9/11. Decades before the terrorists commandeered the planes, Hoffer wrote:

All the true believers of our time declaimed volubly. . . on the decadence of the Western democracies. The burden of their talk is that in the democracies people are too soft, too pleasure-loving, and too selfish to die for a nation, a God, or a holy cause. This lack of a readiness to die, we are told, is indicative of an inner rot—a moral and biological decay.

Since then, journalists have cited the book as a source to explain both the creation of the Tea Party on the right and the Occupy Wall Street movement on the left.

In 2016, presidential candidate Hillary Clinton, to better understand her opponent Donald Trump and his followers, read what she later wrote was Hoffer’s “exploration of the psychology behind fanaticism and mass movements, and I shared it with my senior staff.”

For readers today, Hoffer’s descriptions of the nature of these movements and the people who join them are timelier and more trenchant than ever. The book—the paperback edition is fewer than 170 pages—is divided into 125 “chapters” ranging from a few sentences to several pages. These are mostly epigrammatic observations that build into a portrait of the personalities and forces that create mass movements.

As The Wall Street Journal wrote: “If you want concise insights into what drives the mind of the fanatic and the dynamics of a mass movement at their most primal level, may I suggest an evening with Eric Hoffer.”

I first learned of The True Believer in the summer of 2020. I was out of the U.S. getting my PhD in psychology at the University of Cambridge. I had already begun publishing my own social observations, which led to an interview with a Dutch media outlet on cancel culture. The interview was posted and got a lot of views, which prompted the head of the outlet to take it down because he felt I was too sympathetic to the canceled.

I wrote a piece in Quillette on the irony of being canceled for expressing my thoughts on the canceled, and noted, “The U.S. used to export Coca-Cola, television shows, and music. Today, we export outrage, deplatforming, and social mobbing.”

A fellow student in my program saw the piece and told me I had to read The True Believer. I did, and like Eisenhower, it quickly became one of my favorite books. There were passages—published in 1951!—that seemed to describe how the rise of intellectual and social orthodoxy on campus, and across a growing number of institutions, stifles debate and free expression. More than that, Hoffer captured how in the age of smartphones and social media, people fear the consequences of uttering a single wrong word. He wrote:

[I]n a mass movement, the air is heavy-laden with suspicion. There is prying and spying, tense watching, and a tense awareness of being watched. The surprising thing is that this pathological mistrust within the ranks leads not to dissension but to strict conformity. Knowing themselves continually watched, the faithful strive to escape suspicion by adhering zealously to prescribed behavior and opinion. Strict orthodoxy is as much the result of mutual suspicion as of ardent faith.

He warned in The True Believer, and in later books and interviews, about the dangers for American society of the rise of the intellectual elites. A biographer of Hoffer, Tom Bethell, quotes Hoffer saying that nowhere else was there “such a measureless loathing of their country by educated people as in America” and that this elite want America to be “not a melting pot but a seething cauldron.” These self-anointed experts sought a society “in which planning, regulation, and supervision are paramount, and the prerogative of the educated.”

Hoffer also described how language gets enlisted as a marker of who really is a true believer:

Simple words are made pregnant with meaning and made to look like symbols in a secret message. There is thus an illiterate air about the most literate true believer. He seems to use words as if he were ignorant of their true meaning. Hence, too, his taste for quibbling, hair-splitting, and scholastic tortuousness.

I wonder what Hoffer would make of a world in which some words are so pregnant with meaning that the phrase “pregnant women” has become verboten.