The Free Press

It’s been a rough several weeks for New York City mayor Eric Adams, whose political fate hangs in the balance. His deputies are quitting left and right. Manhattan’s top prosecutor and six others resigned after the Department of Justice ordered her to drop the corruption charges he’s indicted on—and while Governor Kathy Hochul decided against removing him from office, she introduced more strict oversight over Hizzoner.

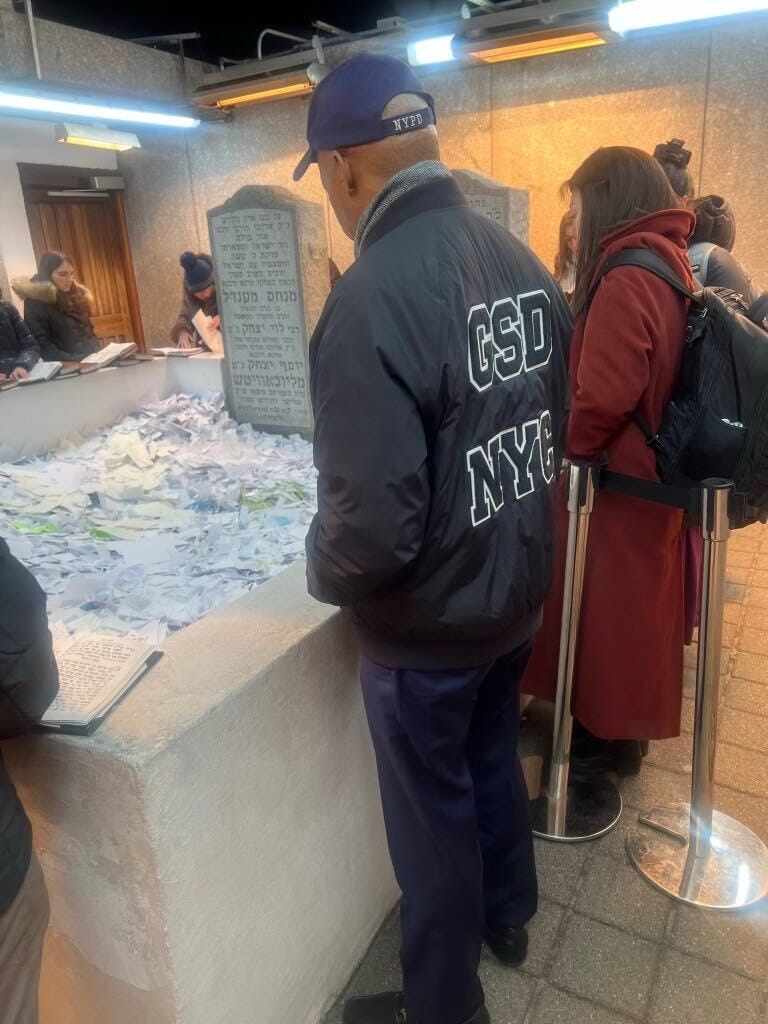

Don’t be surprised to find the embattled Adams making the rounds on Fox News in a bid to cozy up further to the Trump administration. Or blowing off some steam at Zero Bond, his favorite private club in Manhattan. Or, failing those routes, communing with a higher power, at the grave of a late rabbi in Cambria Heights, Queens. This past Tuesday, in a New York Police Department windbreaker and baseball cap, Adams stood gazing at the grave of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the leader of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement, and perhaps the most influential rabbi of the last few centuries before his death in 1994. According to the mayor, “I prayed for strength and global peace.” And probably a few other things.

And well, it worked last time.

“When I was running for office and Andrew Yang was measuring for the drapes because he thought he was going to be the mayor, Devorah Halberstam told me that she had a dream that the Grand Rebbe wanted me to visit his site,” Adams told reporters recently. “And as you know, today we are saying Mayor Adams and not Mayor Yang.” Halberstam is an activist against antisemitism and a close adviser to the mayor.

The squat brown awning jutting out from the door of one of the homes on the corner of 227th Street and Francis Lewis Boulevard, emblazoned with the words Ohel Chabad Lubavitch, isn’t where you might expect world leaders to congregate. The Ohel is situated on a residential block in Queens, out near JFK airport. There are no areas for press conferences, flags, teleprompters, or even central heating. But the site has become one of the most important places for politicians—whether to be seen by constituents, make a statement, or put in a word with the big guy, in a place regarded by many, both Jews and non-Jews alike, to be holy.

At the Ohel, you might be liable to spot one of the state’s senators; a foreign prime minister; or the current president, who paid a visit, flanked by Secret Service; along with Ben Shapiro, and families of Israeli hostages before the election this year to mark the anniversary of the October 7, 2023 attacks on Israel. Trump vowed to return after he won, although there are rumors in the Orthodox world that he might be sending J.D. Vance or Marco Rubio in his stead.

“There’s nothing opulent about it,” said Rabbi Motti Seligson, a spokesman for Chabad who accompanied me to the Ohel recently. We sat at a simple table, past the entrance where wooden benches face a flat-screen playing hours of videos of the Rebbe speaking, in one of the areas where people might read, pray, or write a note to be placed graveside. To our left, up some stairs then down a ramp, is a door that leads onto a cement path that cuts into the vast Montefiore Cemetery and into a small rectangular stone structure which surrounds the graves of Schneerson, and his father-in-law, who was the Rebbe before him. Sitting atop the grave is a thick layer of papers, crumpled handwritten notes and prayers, in front of the two tombstones which are inscribed in Hebrew. Men and women, who stand separately, quietly pray. Inside the visitor’s center, there’s free coffee and cookies, and a stream of people—some of whom are visibly religious, others not so much, coming in and out, a few lugging suitcases, having come straight from the airport.

Seligson estimates that every year the Ohel draws a million visitors from across the globe, and counting the notes they bring with them, there are, he said, “millions and millions of prayers that come through each year.”

In the past few years, those prayers have included those of some of the most powerful people on the planet. While the black-tie Alfred E. Smith Memorial Dinner in Manhattan or the staged-casual appearances at the Iowa State Fair—or last year, appearing on The Joe Rogan Experience—have become mileposts in grueling campaign cycles, the Ohel has emerged as a more modest, mystical stop.

Javier Milei, the president of Argentina, has visited the Ohel at least four times, most recently this past September during the UN General Assembly. Edi Rama, the prime minister of Albania, who is Catholic, was spotted there around the same time. Late last month the governor of São Paulo, Brazil, spent an hour at the Ohel. RFK Jr. visited two summers ago while he was still running for president, and Kathy Hochul was spotted there during her gubernatorial reelection bid. Senator Kirsten Gillibrand paid a visit on Election Day this past November. Cory Booker was spotted at the Ohel the night before he announced he’d be running for president in 2020. Senator Booker is known to visit the open-air mausoleum, the most popular Jewish site in North America, to pray on the eve of his elections, in private. Booker, who has been making personal visits there for over 30 years, told The Free Press, “I am not Jewish, yet there is something universally spiritual about that sacred space. I find my visits are both grounding and expanding.”

He added that he spends his time at the Ohel “in reflection, contemplation, meditation, and prayer.”

Ivanka Trump and her husband, Jared Kushner, tend to come late at night—the site is open 24/7. Not to mention senatorial and congressional hopefuls, and throngs of Israeli dignitaries and government advisors. Mayor Adams has made at least seven trips to the Ohel, and the three visits since he was indicted in September for corruption, including the one this past week. “When I go through difficult times I found that I visit their gravesites and their energy materializes things that I look for,” he said.

I asked Halberstam, who took Adams the first time he visited, if she thinks politicians go there for the votes of the Jewish bloc, but she brushed me off. “I can’t see into people’s hearts and minds.” On Adams, she said, “For this mayor, it’s the real deal. He’s a spiritual person. He walks with God.”

Author of the Schneerson biography Rebbe, Rabbi Joseph Telushkin told me that while he was alive, the Rebbe “ventured into the world of politics but he remained very apolitical.” The Rebbe encouraged the formation of the Department of Education in the ’70s, for example, and he corresponded with both Presidents Carter and Reagan—the former of whom would establish the Department in 1979 and dedicate the Rebbe’s birthday as a national “Education and Sharing Day.” He met with Robert Kennedy a month after the former U.S. attorney general announced his senatorial bid—they debated financial aid policies for families to send their children to religious schools.

He was something of a one-man foreign policy operation, once telling Morocco’s ambassador to the United Nations, “It will be a good idea to add a Chabad house in Morocco. And certainly the king will be happy about it.”

“He wasn’t doing it for any game. There was no contract they were going to get. There was never any mixing of motives,” Telushkin told me. “He was taken seriously.” Seligson put it like this: “The Rebbe was about uplifting people and helping people live a better, more elevated life, and that goes with impact as well. Politics and policy are all downstream of that.”

In death as in life, the glittering dignitaries come to the Rebbe, not the other way around. In 1977, then newly elected Prime Minister Menachem Begin directed his motorcade to the Rebbe’s in Brooklyn on his way to his first meeting with President Carter in Washington, talking with Schneerson for nearly three hours. He told reporters afterward that the content of their meeting was “between us.”

As far as special precautions in Cambria Heights, there’s a low-key police presence, and politicians might come flanked by security or body men, though Seligson assured me the site is “also protected by a higher authority.”

Though the notes politicians leave for the Rebbe are private—it’s customary to rip up the paper before placing it in the grave—Seligson doubts the letters contain pleas to win over women aged 18-35 or to ask for a boost in Bucks County.

In 2015, Victor Espinoza, the Mexican jockey who had won the Kentucky Derby and the Preakness riding the horse American Pharoah, came to pray at the Ohel on the day before the Belmont Stakes. “This was the pinnacle of his career,” Seligson told me. He told reporters he prayed for his health, and his family. Espinoza won the next day, becoming the first jockey to ride a Triple Crown winner in 37 years.

As far as the fact that the Rebbe is still, more than 30 years after his passing, drawing influential people at times of peak importance for them, Telushkin said it has to do with an ethereal inversion: “For most people their ability to impact is based on their being alive, but there’s a certain impact of holiness where even after their death, it continues.”