The Free Press

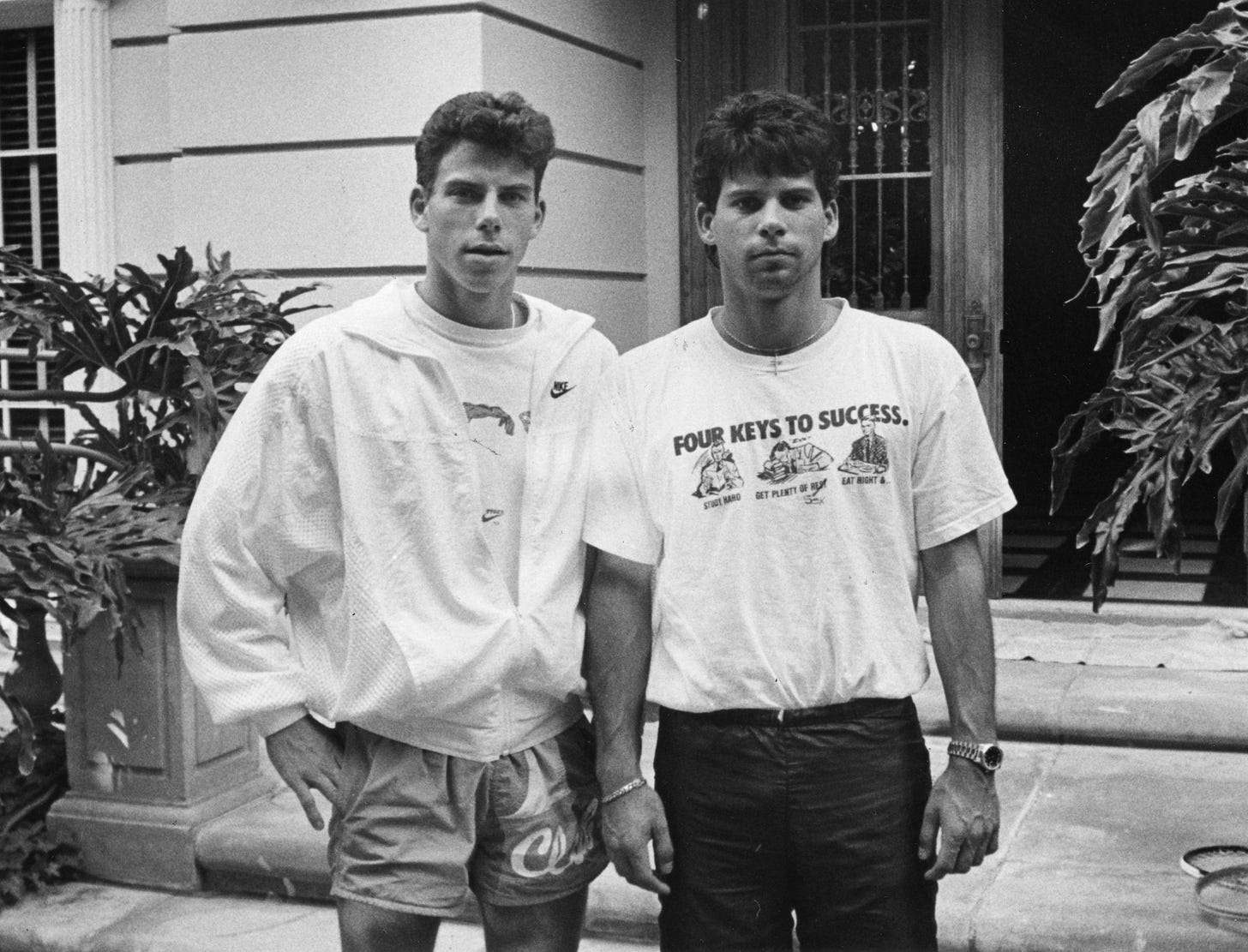

This week, after delays, plot twists, and a letter of support from Kim Kardashian, Lyle and Erik Menendez may finally learn if they will be resentenced for the 1989 murders of their wealthy parents, José and Mary Louise “Kitty” Menendez. Their original sentence was life without the possibility of parole. Now parole, or even early release, might be possible.

What changed? Two new pieces of evidence emerged, which seem to support the brothers’ early claims they were physically and sexually abused by their father, José Menendez, a high-profile music executive. The first is a bombshell letter Erik apparently wrote to his cousin Andy Cano eight months before the murder. Cano passed away in 2003, but author Robert Rand unearthed the note in 2018, when he was writing a book about the Menendez brothers and their aunt gave him permission to look through Cano’s bedroom.

The letter seems to reference the abuse, saying, “It’s still happening, Andy, but it’s worse now. . . . Every night I stay up thinking he might come in. . . . I’m afraid. You just don’t know dad like I do. He’s crazy! He’s warned me a hundred times about telling anyone.”

The second piece of evidence centers on testimony from Roy Rosselló, a member of the boy band Menudo. In 2023, Rosselló alleged he had been sexually abused in 1983 by José Menendez, who worked with the group when he led RCA Records. When Netflix released the nine-episode miniseries Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menendez Story last year, detailing the abuse claims, it further fueled a national conversation over whether the brothers were fairly sentenced and should be released.

Here’s what we know happened on the evening of August 20, 1989: José and Kitty were watching The Spy Who Loved Me in the theater den at their Beverly Hills mansion, when Erik, then 18, and Lyle, then 21, showed up with loaded shotguns. The brothers walked into the room and opened fire. Then, one of them put a gun directly in José’s mouth and blasted off the back of his head. When Kitty tried to “sneak away,” Lyle—a Princeton dropout—reloaded his shotgun and fired at her again. The brothers shot José a total of six times and Kitty 10 times. They carefully picked up their shell casings and fled, only to return an hour and a half later to call 911 and pretend they’d just discovered the bodies. Lyle and Erik insisted it must be a hit job, related to their father’s sketchy business dealings.

After the murders, the boys went on a spending spree, buying Rolexes and other luxury goods. Erik eventually confessed their crime to his therapist, who reported it to the police. Cornered, the brothers said they’d been sexually abused for years—not only by José but sometimes by Kitty as well. Erik claimed their father “massaged” his penis and performed oral sex on him regularly for more than a decade, all the way up to the summer of the killings, when he was 18. Lyle claimed José raped him between the ages of 6 and 8, and that Kitty made him touch her sexually as they slept next to each other.

“I believe the Menendez brothers should get an early release.” —Sally Satel, a psychiatrist and senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute

In 1993 the boys were tried separately, but both trials ended in hung juries. Prosecutors dismissed their claims of “imperfect self-defense” related to their abuse, and claimed the brothers killed their parents because they stood to inherit $14 million. (In the end, the Menendez mansion was sold at a loss, with all proceeds covering the mortgage, sale costs, and tax obligations.)

The following year, the brothers were tried together. The judge refused to allow the “abuse excuse” in court, and they were sentenced to life without parole.

Now, as childhood trauma is increasingly presented as a mitigating factor in all types of violent criminal cases around the country, the brothers are hoping—at a hearing on April 17 and 18—to make their case for parole or release. And, at a time when defense attorneys are pointing to abuse, poverty, hunger, the death of loved ones, and other traumatic childhood experiences to help their clients get lighter sentences, they could win the argument.

“People are becoming more sympathetic to claims of childhood abuse,” said Douglas A. Berman, a criminal law professor and executive director of the Drug Enforcement and Policy Center at Ohio State University.

Sally Satel, a psychiatrist and senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, is one person who sees good reason to release the brothers. She said the Menendez brothers pose a “low risk” to society, and that the murder was a response to their abuse. And, she notes, Erik and Lyle did not have a history of violence before the murder. Plus, they’ve behaved well in prison, and during their incarceration they initiated new programs that helped their fellow prisoners.

“These are people who are not a menace to society,” Satel said. “Their violence was very targeted. And there was a logic to it. I’m not saying it’s excusable in any way, but it was retribution. They weren’t just randomly seeking out people to gun down in their living rooms.”

To Satel, it’s clear. “I believe the Menendez brothers should get an early release,” she said.

The Menendez case raises important questions: Should childhood trauma influence the punishment of an adult for violent crimes? Can it even justify murder? The general public’s feelings about these issues have shifted over time.

When Lyle and Erik ambushed their parents, sentencing practices were evolving in the U.S. In 1984, Congress enacted the federal Sentencing Reform Act, which provided judges with basic rules for sentencing—without mentioning childhood trauma or any other mitigating factors, Berman said.

That left the door wide open for defense attorneys to argue for lighter sentences for their clients who had experienced childhood difficulties or trauma.

“A bunch of defense attorneys said to the judges, ‘Look at the poverty that my client lived under. You should give them a lower sentence because of that,’ ” Berman said. “That’s what we might call ‘a rotten social background’ story. And somewhat problematically, half the judges said, ‘Yeah, you’re right,’ and the other half said, ‘No, that’s not what we’re supposed to do.’ And partially because of that disparity, the sentencing commission wrote a new rule that said, ‘Do not consider that stuff.’ ”

In 2005 the tides changed again, allowing federal judges to take into account almost any mitigating factors they chose. And, if we accept that sexual abuse can be a mitigating factor, “it would only be fair” to consider all factors, said Dr. Paul S. Appelbaum, professor of psychiatry at Columbia University and former president of the American Psychiatric Association.

“A large number of variables in decades of research have been associated with an increased risk of violence, including growing up in poverty, losing a father before the age of 16, parental drug and alcohol use,” Appelbaum said.

The key question for a sentencing decision, according to Appelbaum, is to what extent these factors justify or partially excuse the violent behavior. “That’s much more difficult to answer,” he said. “Most people who grow up in poverty are not violent. Most people who lose their fathers before the age of 16 are not violent. Most people whose parents abuse alcohol or drugs are not violent, and most people who are abused as children are not violent.”

Berman said the whole issue reminds him of the “great West Side Story song ‘Gee Officer Krupke!,’ where everybody is pleading why they’ve done something bad. It’s the very same story of: ‘Hey, when I grew up, my father beat me, and that’s why I did this wrong.’ ‘No, the problem is, I don’t have good self-esteem, and that’s why I did it.’ And that was written literally 80 years ago. These issues are enduring human realities.”

In October 2024, then–L.A. district attorney George Gascón became the first person of authority in California to recommend a resentencing for Lyle and Erik Menendez, saying, “Our office has gained a deeper understanding of the complexities surrounding sexual violence. We recognize that it is a widespread issue impacting individuals of all gender identities, and we remain steadfast in our commitment to support all victims as they navigate the long-lasting effects of such trauma.”

But in November, the progressive Gascón was ousted by Nathan Hochman, a self-described “hard middle” candidate. Hochman highlighted the brothers’ gruesome crime, said the scene was staged to look like “a mafia killing,” and asked the court to throw out the resentencing request. Last week, the court denied Hochman’s bid and ruled that the resentencing hearing could move forward as scheduled this week.

All legal eyes will be on the case to see which way the judge decides—and the implications it will have on criminal justice in America. Mandating that childhood trauma should be a mitigating factor will invite lots of creative interpretations, Berman said.

He pointed to the example of Ethan Couch, the wealthy 16-year-old Texan who killed four people in a DUI accident after playing beer pong and drinking Everclear grain alcohol. Berman summed up the defense’s excuse for Couch’s crime: “I’m afflicted with affluenza. I grew up in such an affluent home that it really was an abusive childhood, because my parents were just throwing money at me and they weren’t giving me any guidance. So reduce my sentence.” Couch was sentenced to two years in jail.

This is part of what makes the Menendez case so engrossing, Berman said. “Even though the parents were hardscrabble and made it, the kids were spoiled brats,” Berman said. “Yet they had a tough childhood.”

For more on this topic, read Alan Abrahamson’s piece, “Don’t Feel Sorry for the Menendez Brothers.”