The Free Press

The 1997 murder trial of Louise Woodward was the first time many Americans heard of shaken baby syndrome. A teenage British nanny working in a wealthy Boston suburb, Woodward was accused of handling 8-month-old Matthew Eappen so roughly he fell into a coma and later died. It was a clear case, prosecutors alleged, of an increasingly prominent medical diagnosis that was tantamount to a criminal accusation. Juries across the country were accepting it as proof of caregivers’ guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

The trial was an international sensation—supporters gathered in a pub in Woodward’s home village to watch the televised sentencing. The case underscored class divisions as well as a simmering anti-feminist backlash: See what happens when mothers don’t stay home with their babies?

Woodward’s defense was led by attorney Barry Scheck, a co-founder of the Innocence Project, who was fresh off O.J. Simpson’s “dream team.” He put the diagnosis of shaken baby syndrome itself on trial. “I literally went back and read every paper in this field that we could find and asked doctors to explain to me every term,” Scheck told 60 Minutes Australia in 2022.

Scheck’s team found that a growing number of researchers and physicians had major doubts about the theory, and several of them testified in Woodward’s defense. Their argument was that the diagnosis relied too heavily on subjective interpretation and that a generation of clinicians had been “indoctrinated” to believe that a baby presenting with the symptoms of Eappen pointed to a single cause: violent shaking. But Scheck argued, as he later said of the Woodward case, “The scientific evidence demonstrated that she did not do this.”

After a three-week trial, Woodward was found guilty of second-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison. But Scheck and his co-counsel had succeeded in casting enough doubt on the cause of death that the judge, while not exonerating Woodward, reduced her conviction to involuntary manslaughter and her incarceration to time served. She returned to England, where she studied law, married, and had a child. Her case continues to grip the public, and is periodically revisited by documentary filmmakers.

Although Woodward’s case put a spotlight on the questionable science behind shaken baby syndrome, today, mothers, fathers, and caregivers are still being prosecuted for it. It is estimated that over the decades thousands have been accused, and many convicted, of harming or killing a child by shaking.

Now, more than a quarter of a century later, Scheck is again putting shaken baby syndrome on trial. The Innocence Project has taken up the cause of exonerating Robert Roberson, a man who has spent more than 20 years on death row in Texas—mostly in solitary confinement—for the 2002 death of his 2-year-old daughter, Nikki.

Gretchen Sween, Roberson’s attorney since 2016, took his case after Texas passed a law allowing courts to revisit prosecutions based on “junk science.” But Sween told me that the state has consistently blocked her efforts to have Roberson’s case reheard. Her latest effort was filed February 19 in the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, asking that Roberson be declared innocent based on new evidence or be granted a new trial. If Texas executes Roberson, he will be the first person put to death for a conviction linked to the shaken baby diagnosis.

His case has attracted a high-profile group of supporters, including the novelist John Grisham, billionaire entrepreneur Richard Branson, and television psychologist Dr. Phil McGraw. They are working to expose how bad forensic science gets so embedded in the medical and criminal justice systems that actual innocence becomes almost impossible to prove. With shaken baby syndrome, the last adult with the child is essentially presumed guilty.

“Roberson suffered the same horrific fate as my former client Louise Woodward—he was wrongly convicted of killing his daughter based on the now discredited shaken baby syndrome (SBS)—a ‘diagnosis’ that was not evidence-based medicine,” Scheck, 75, told The Free Press via email.

“Over the last two decades, extensive scientific research has discredited SBS,” wrote Scheck. But “because misinformation and misconceptions about SBS persist, Mr. Roberson is still at risk of execution for a crime that never occurred.”

What Happened to Nikki

In the early morning hours of January 31, 2002, in Palestine, Texas, Roberson’s daughter Nikki stopped breathing while sleeping next to him in bed.

Nikki’s short life was marked by poverty, dysfunction, and illness. When she was born in East Texas, the state took her away from her mother, who was homeless and using drugs. The baby was placed with her maternal grandparents. Like the two infants previously removed from their mother, Nikki was sickly: She suffered from chronic infections and apnea, which would cause her to stop breathing. In the five months leading up to her death, she had been taken to the doctor a dozen times.

Roberson had a ninth-grade education and a rap sheet: He had served time for nonviolent robbery and passing bad checks and was back in prison for a nonviolent probation violation when Nikki was born. When his sentence was up, he got a job delivering newspapers and sought custody, which he won in late 2001. “He’s a poor guy trying to do right by this child,” Sween told me.

Days before Nikki’s death, Roberson, then 36, took his daughter to the emergency room. She was coughing and unable to keep food down. A doctor sent them home with a prescription, where her fever got worse. The next morning, Roberson took Nikki to the pediatrician. She had a temperature of 104.5, but was again sent home with more of the medication. That evening, Roberson tucked Nikki in his own bed—the same arrangement she had at her grandparents—and they drifted off to sleep.

In the middle of the night, Roberson told medical staff, he woke to a “strange” cry and found Nikki on the floor. In his account, she had some blood on her lip but otherwise seemed alright, and they fell back asleep. But in the morning, Nikki was unresponsive—and blue. He rushed her back to the emergency room, where she was resuscitated and prepared for transfer to a Dallas children’s hospital.

A nurse suspected abuse and alerted local police. The detective who interviewed Roberson was troubled by his flat affect. Roberson asked to accompany Nikki to Dallas, but was told he couldn’t.

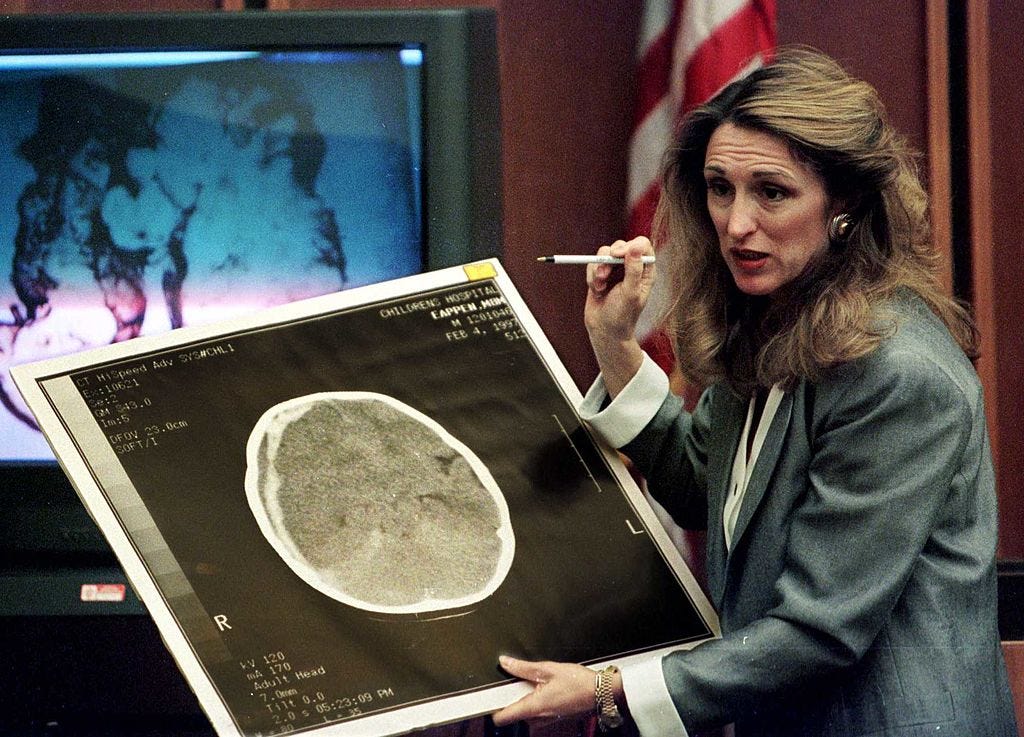

In many hospitals, when a young child arrives in an emergency room, a process unfolds to identify if the patient is a victim of violence. In Dallas, a physician trained in the emerging specialty of child abuse pediatrics examined Nikki and concluded the “only reasonable explanation” was traumatic injury—a conclusion that made Roberson a homicide suspect. Within hours, Nikki was taken off life support and Roberson was charged with capital murder. A year later, he was convicted and sentenced to death.

A New Diagnosis

When the hypothesis that shaking a baby could cause brain damage entered pediatrics in the 1970s, it was part of a wave of movements in the U.S. seeking to make children safer. Domestic abuse was shedding its long history as a private source of shame and gaining recognition as a legal and social issue that required intervention—and if necessary, criminal prosecution.

The 1974 federal Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act made doctors, teachers, and social workers “mandated reporters,” professionals who were now required to notify officials if they suspected violence or neglect. States established hotlines administered by Child Protective Services, agencies with growing funding and power that could potentially present findings to law enforcement.

It was research into the potential harms of motor vehicles that led to the shaken baby hypothesis (and subsequent laws requiring seatbelts and child car seats). British neurosurgeon Norman Guthkelch had read about whiplash experiments on monkeys, which demonstrated that sharp back and forth motion alone could cause brain injury without direct impact. He theorized that caregivers, who shook children in frustration or anger, could cause the same damage.

Of course, when a baby or young child unexpectedly falls unconscious or dies, society rightfully wants to know why. But sometimes there is no obvious cause, no visible injury, no immediate explanation. Shaken baby syndrome provided one. (To be clear, child abuse is a serious problem, and babies should never be violently shaken.)

In the U.S., John Caffey, a Pennsylvania pediatrician, took Guthkelch’s suppositions further and published a template for signs that a baby had been shaken: bleeding between the brain and skull, in the back of the eyes, and swelling in the brain. This “triad,” as it is known, was swiftly accepted as definitive and became standard in the worlds of both medicine and criminal justice.

By the 1980s, televised public service announcements warned frustrated parents not to shake a crying baby. And for years, Congress authorized the third week of April National Shaken Baby Awareness Week. On a grand scale, gentler parenting replaced the paddle in the United States: The estimated prevalence of spanking plummeted from 80 percent in 1975 to 35 percent in 2020.

At the same time, there were signs that the noble cause of stamping out child abuse had taken a bizarre turn. The first was “recovered memory syndrome.” Adults—mostly women—were encouraged by self-help books and therapists to “recover” suppressed memories of childhood sexual abuse, which would explain everything from anxiety to joint pain. These memories turned out to be overwhelmingly false, implanted by the therapists themselves. Eventually, lawsuits and exposés by journalists revealed how the power of suggestion had fomented a moral panic that tore apart thousands of families.

Running parallel was spreading fear of “satanic ritual abuse” of children. This grew into a witch hunt that led to thousands of accusations of lurid and ludicrous abuse of toddlers by day-care providers. Prosecutions resulted in dozens of convictions, decades-long sentences, and ruined lives.

In their 2014 documentary The Syndrome, Meryl and Susan Goldsmith attribute the rise of shaken baby syndrome in part to this disorienting chapter. After evidence of widespread satanic torture failed to materialize, several of the physicians who gave credence to the phenomenon pivoted in the 1990s to advocacy about fatally shaken babies.

By then, prosecutions for shaken baby syndrome were proving highly effective, frequently winning convictions against the accused. In these cases, typically the defense asks juries to accept that we may never know how or why an infant died. Signs of damage to the brain, juries are told, can have numerous causes, often completely unrelated to abuse. The prosecution, on the other hand, offers certainty. Prosecutors call on expert witnesses—specialists in child abuse—who confidently assert that a child’s caregiver delivered mortal damage.

Challenging the Syndrome

As convictions based on shaken baby syndrome rose, so did questions about the reliability of that diagnosis. In 2001, seminal research on playground accidents by a Minnesota forensic pathologist and medical examiner demonstrated that a fall from even a short height, or an object falling on a child, could generate brain swelling and bleeding. The pathologist, John Plunkett, began testifying in court on behalf of defendants accused of shaken baby syndrome. As a crime reporter for The Washington Post put it, “Plunkett was now a threat to SBS cases all over the country.”

Pediatric radiologists were also raising alarms. Dr. Julie Mack was in practice in the early 2000s in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and had pronounced many shaken baby diagnoses after reviewing CT scans. “In med school everybody was taught” that if you couldn’t readily explain the cause of brain swelling and bleeding, “the parents must be hiding something,” she told me.

To address her growing doubts about this dogma, she explored the anatomical literature and had a breakthrough. She found that the dura, the membrane between the skull and the brain, can bleed without trauma—resulting in a “subdural hematoma”—one of the supposed key markers of SBS. Mack co-authored a widely cited paper with Dr. Waney Squier, a British neuropathologist who specialized in infant brains.

Squier also dove into the literature and found that subdural hematomas are a common artifact of childbirth. Around half of babies have them and they can last for several months. Furthermore, bleeding in the dura and behind the eyes can be triggered by an infection, a genetic disorder, diabetes, cancer—the list of conditions that share these symptoms is “ever expanding,” said Mack.

Squier told me she “became completely convinced there is no good evidence” to support the shaken baby syndrome hypothesis.

She was also concerned that defaulting to shaken baby syndrome meant clinicians were not recognizing and treating what was actually wrong.

She told me about a case in France, the subject of the 2022 documentary Jusqu’à l’appel (available here), in which the brain scan of a sick baby showed a subdural hemorrhage. This led to the father being accused of shaking. But the child actually had meningitis, failed to get the necessary antibiotics, and died. Squier said of the physicians in charge, “They killed that baby.”

When Guthkelch came to understand what had been spawned from his original hypothesis, he devoted his retirement to assisting people accused of criminally shaking a baby. Shortly before his death in 2016, he told a journalist: “I am frankly quite disturbed that what I intended as a friendly suggestion for avoiding injury to children has become an excuse for imprisoning innocent parents.”

Exonerations

It’s impossible to say how many people have been charged with shaken baby–related crimes. Family court has tight disclosure rules to protect minors, and the charge is homicide or aggravated assault, not shaking.

To try to understand the breadth of how this diagnosis has resulted in criminal charges, in 2015 The Washington Post and the Medill School of Journalism uncovered 1,600 cases resulting in a conviction that implicated shaken baby syndrome.

To date, there have been 36 exonerations related to SBS, according to a recent ProPublica/New York Times investigation. The stories are chilling.

In 2021, a Georgia couple was released after serving 12 years in prison stemming from a diagnosis of abuse. Ashley and Albert Debelbot had been home for just 12 hours after the birth of their daughter, McKenzy, when they brought her back to the army hospital in Fort Benning, Georgia. Soon they were grieving their baby’s death—and being arrested.

The medical examiner testified at their 2009 murder trial to “very severe head trauma,” the couple was convicted, and both got life sentences. The Wisconsin Innocence Project and others took on the case, which was overturned on a technicality. Experts contended the actual cause of death was a fatal blood clot that developed before McKenzy’s birth.

In 1997, a Texas man, Andrew Roark, was babysitting for his girlfriend’s 13-month-old child when he called 911 to say she had fallen off her bed and was unconscious. (She survived.) He was prosecuted and convicted on SBS-related injury charges. After serving 15 years of his sentence, in November he was exonerated. The original determination of shaking was made by the same Dallas physician who diagnosed Roberson’s daughter Nikki. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals noted in a ruling in Roark’s case that “scientific knowledge has evolved regarding SBS.”

Child Abuse Pediatricians

After the Louise Woodward case raised questions about shaken baby syndrome, activist physicians and social workers who ardently believed this syndrome was a widespread problem pushed hard against the doubters.

In 2000, a group of advocates founded the National Center on Shaken Baby Syndrome, which lobbied states to pass laws requiring education in identifying SBS and helped expand the medical subspecialty of child abuse pediatrics.

In 2009 the American Academy of Pediatrics subsumed shaken baby syndrome under the new classification of “abusive head trauma” (AHT). In a 2020 update, the organization wrote it “continues to embrace the ‘shaken baby syndrome’ diagnosis as a valid subset of the AHT diagnosis.” Deborah Tuerkheimer, Northwestern law professor and author of Flawed Convictions: “Shaken Baby Syndrome” and the Inertia of Injustice, told me: “This is a story of a diagnosis that keeps changing, but changes in ways that allow it to be salvaged.” Last week the AAP issued a new report on abusive head trauma that barely mentions SBS. (The group declined to comment for this story.)

In spite of the growing concern about SBS-related prosecutions, the medical community largely continues to support the diagnosis. Dr. Lori Frasier, a pediatric child abuse specialist in Hershey, Pennsylvania, on the board of the National Center on Shaken Baby Syndrome, told me that if caregivers are wrongfully convicted, that’s the fault of the justice system. “Our job is to do the medicine, not to rely on what happens in the courtroom.”

Kate Judson is the executive director of the Center for Integrity in Forensic Sciences, founded in 2017, which seeks to ensure that scientific evidence presented in criminal courts is valid and reliable. She says dubious cases involving SBS accusations land on her desk weekly. Judson told me the American Academy of Pediatrics and pediatricians who specialize in child abuse “have been extremely hostile to any suggestion that they may have gotten it wrong.”

New Evidence About Nikki

At Robert Roberson’s murder trial in 2003, the jury was told that Nikki’s symptoms could point only to one thing: that she’d been violently shaken. Even Roberson’s court-appointed attorney, the person charged with defending him, conceded throughout the trial that this was a “classic shaken baby” case.

Last September, Roberson’s attorney Gretchen Sween filed a petition for clemency that includes several new, exonerating findings. For instance, Nikki had been prescribed a drug that combines an antihistamine and a narcotic. Today the Mayo Clinic warns the medication “is not recommended in children. . . because of the increased risk of respiratory depression.”

The jury was also repeatedly told that Roberson’s lack of emotion should be viewed with suspicion, but in 2018 he was diagnosed with autism, which helps explain his flat demeanor.

Even the detective who helped convict Roberson, Brian Wharton, has since recanted. “Our bedrock accusation, ‘Shaken Baby Syndrome’ as used in Robert’s trial, is junk science,” he wrote in a letter to the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles. “There is no evidence of a crime, much less a capital crime.”

On October 17, 2024, Roberson was scheduled to die, but he was saved by a bipartisan group of state legislators who issued a subpoena asking him to testify before them, which led to the Texas Supreme Court delaying his death. There is currently no execution date. But Sween says that could change at any moment.

In the petition she filed in February, Sween includes the findings of 10 pathologists who call the medical examiner’s determination of violence “not reliable.” There is also a new statement from a Roberson family friend who says child protective service caseworkers threatened to take her children away if she didn’t “get on board” with testifying against Robert. “This pressure did not work on me,” she said.

Last October, members of Nikki’s family on her mother’s side issued a statement calling for Roberson’s execution. It read, in part, “We believe his death sentence should be carried out based on the facts of this case, which remain true today, as well [as] the overwhelming evidence that was presented at the trial that led to the jury’s verdict.”

Roberson’s attorneys did not make him available for comment for this story. But members of his family have long stood behind him and continue to assert his innocence. In a statement to The Free Press, his younger brother Thomas said, “No one who knew Robert well believed he was capable of harming any child. And to this day, I am convinced that he could not have done what he was accused of doing. . . . Every time I visit Robert at the prison he is always smiling and so positive. He says he is in God’s hands.”

The Free Press earns a commission from any purchases made through all book links in this article.

Once upon a time, honorable men went to the gulag for refusing to repeat the Kremlin’s lies; now an American president is telling them for free. In the latest episode of Breaking History, Eli Lake takes us back to the Cold War and President Reagan’s support of dissidents.