The Free Press

In a few short weeks, Donald Trump will be sworn in as the 47th president. His transition team will be in charge of a federal government that, in many rudimentary ways, doesn’t work.

Let’s leave aside partisan gridlock in Congress and turmoil in the judicial branch, and just focus on the executive branch: National Public Data, which aggregates personal information for background checks, was hacked this year, meaning your Social Security number is now floating around on the internet. The IRS is built on mainframes from 1965 and relies on code from JFK’s administration that no one’s learning anymore. The pandemic highlighted our broken systems: In January 2020, the Food and Drug Administration effectively banned private companies from rolling out their own Covid tests because the CDC was developing their own. But the CDC tests turned out to be defective, leaving the U.S. flying blind until private companies could rush in and pick up the slack.

For the past year, I’ve run an interview series called Statecraft where I talk with civil servants to understand how the federal sausage actually gets made. These men and women serve in a variety of roles, such as running a CIA base in Afghanistan, investigating Soviet anthrax leaks, and redesigning Department of Labor job centers. The best of them have managed to deliver good outcomes for the American people by working around the worst ingrained practices of the federal bureaucracy, and they have lessons for reformers eager to make the federal government go.

But changing the culture of a machine this size takes time. Despite the fact he will have a Republican House and Senate, and the allyship of Elon Musk, who seems eager to head his own Department of Government Efficiency, Trump faces the same broken federal machinery—and will face many of the same problems, and the shot clock to solve them—that Biden did.

To help make the government more efficient and effective instantly, the Trump team should prioritize the following:

Hire Bureaucrats, Just Make Them the Right Ones

Progressives fear Trump’s vision for civil service reform, Schedule F, which would reclassify many civil servants to make them easier to fire. They worry Schedule F would gut executive branch agencies—which includes the Environmental Protection Agency, the Departments of Education, State, Justice, et al.—of their talent, and consolidate power in the White House.

But even liberals like Jen Pahlka, former deputy chief technology officer of America under President Obama, have pointed out that “managing out” a poor performer can be a full-time job for political appointees. Firing an executive branch civil servant requires extensive documentation. Additionally, many employees are unionized, and all can appeal their firings internally. Partially as a result, the government cans bad employees about four times less often than the private sector does. It takes a lot more than saying “you’re fired” to get people out the door.

It’s also impossible to hire new, better civil servants. Our systems for sourcing are shattered. Take Jack Cable, 17, who won the Department of Defense’s “Hack the Air Force” contest against 600 other contestants by identifying weaknesses in Pentagon software. But when Cable applied for a DoD role, his résumé was graded “not minimally qualified” because the hiring manager didn’t know anything about the coding languages he listed himself proficient in. Or take the Federal Aviation Administration, which has been screening prospective air traffic controllers for how many sports they played in high school in an effort to meet its racial quotas.

A strategic administration will encourage agencies to find creative ways to bring in top talent. It could try using new tools to assess technically talented applicants in bulk, or it could increase the number of academic rotations through the Intergovernmental Personnel Act, which allows academics to contribute part-time to special federal agency projects. The Office of Personnel Management can and should encourage more aggressive use of Direct Hire Authority, allowing agencies to avoid certain procedural steps of the federal hiring process.

Find Out What Authorities You Actually Have

Agency bureaucrats tend to be wedded to incredibly specific processes, from conducting environmental reviews to military equipment procurement. They will tell political appointees that these processes are required by statute. But oftentimes, these processes are just a result of habit, not any law. Like a mollusk that builds its shell through accretion, agencies have a tendency to generate their own internal process requirements over time. Give it five years, and many civil servants will believe their own strictures are actually mandated by Congress. A few more years, and Congress will come to believe that its predecessors must have mandated whatever an agency is doing.

In fact, many of the statutory authorizations for agencies leave room for them to use special contracts that avoid the traditional procurement process. Many more agencies should receive the ability to use challenge prizes, which offer rewards for specific technical innovations, or advance market commitments, in which the government commits to buying a product in development at a given quantity and price in the future.

Consider the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, or SPR: massive salt caverns on the Gulf Coast that house millions of barrels of oil. Traditionally, the SPR has been a rainy day tool: The government dumps oil onto the market in times of crisis and high prices, then refills the reserve when prices are low. But reformers had an idea: If the SPR made commitments to purchase oil at guaranteed prices in the future, those promises would help stabilize oil prices when geopolitical events roiled the market. It worked—for the past year, oil prices have mostly hovered in a sweet spot between $70–90 a barrel—but think-tank wonks had to spend a year convincing the SPR it already had authority to make those future commitments.

Trump’s former head of the Office of Management and Budget once described his philosophy to me: “Political appointees have to be really aggressive in going back to underlying statutes to see what is possible.” His advice should be heeded during Trump’s second term.

Set Ambitious, Concrete Goals

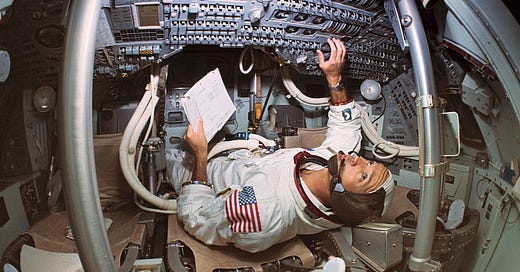

In 1961, JFK famously called for the U.S. to put a man on the moon and return him safely to Earth “before this decade is out.” NASA did it with six months to spare. The target was difficult but achievable, and it was falsifiable: If the agency failed, everyone would know. Both features helped focus the minds at NASA.

By contrast, many of the federal government’s most persistent failures can be tied back to a lack of goal-setting. As one economist pointed out to me, no one in D.C. is explicitly tasked with increasing productivity growth. Small wonder productivity has stagnated since the ’70s.

The next administration should take the same approach that JFK’s administration did. Pick a deadline: maybe America’s 250th birthday in 2026, for which President Trump is already planning a yearlong party, or the end of the decade. Have each agency head pick a verifiable goal for their agency, like building the biggest geothermal plant in the world, or sending a human to Mars, or developing a prototype vaccine for each of the known human viral families. Then commit to those goals in public, and use those commitments to get civil servant rears in gear.

Experiment, Experiment, Experiment

The National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health together are the largest funders of basic science in the world. But despite spending around $60 billion a year through them, we know little about the best ways to support science. How could their grants be more effective? Would administering grant proposals in a different way—via lotteries, or by giving reviewers “golden tickets” to champion specific proposals—encourage more innovative, high-reward proposals? Some agencies are beginning to build out the internal resources to test these hypotheses.

In the early days of the pandemic, the NSF disbursed grants related to Covid much faster than did the NIH, because it used internal review processes instead of sending grants out for external peer review. We use peer review by default in the scientific enterprise, but it may be advantageous to relax these peer review requirements in future crises.

Experiments take time. They also require bureaucrats to get comfortable with iterating—not traditionally a governmental skill. To get time and the freedom to experiment, innovators at agencies will need encouragement and blessing from the top. The sooner they get it, the sooner agencies can figure out what works; if they’re lucky, they’ll sort it out before the midterms roll around. Political appointees should explicitly encourage civil servants to try new things, and stand by them if it goes wrong the first time.

Circuit-break the Interagency Process

The federal government loves to make decisions by unanimous committee, in what’s called the “interagency process.” If the State Department wants to reverse a coup in Mauritania, as it tried to in 2008, it pulls together a committee with representatives from Defense, the National Security Council, Treasury, and other agencies that have stakes in the outcome.

The interagency process is an excellent way to cover asses and diffuse responsibility and, often, a terrible way to make decisions. My first interviewee, Dr. Mark Dybul, who helped develop America’s anti-HIV/AIDS program, described how the process devolves into “blood on the floor, hatchet work.” He added that “Big, bold things cannot be done through an interagency process. They tend to get to the lowest common denominator.”

How do you snap out of interagency gridlock? Use a stick. In 2003, President Bush brought squabbling agency heads tasked with combating HIV in Africa into the Oval Office and made a pointed threat. He said that if they didn’t sort things out, “I will be coming after you.” After that, according to Dr. Dybul, “The fighting dropped off remarkably.” Since then, America’s HIV/AIDS program in Africa has saved 20 million lives. Our next president should pick the right moments to remind executive branch functionaries who the boss is.

Agencies often need to work together to achieve complex goals. But the best collaborative work happens when each player knows that the buck stops with someone.

Presidents come into office with a list of policy priorities and campaign promises, and they don’t tend to be excited about reforming the nuts and bolts part. But they should be.

The feds have gotten real wins in the recent past: Look at Operation Warp Speed, or the IRS Direct File experiment, or the Federal Reserve’s indirect derisking of investment in fracking. Each of these wins came in part because civil servants were willing to challenge procedural norms in some places and to design better procedures in others.

If this administration wants to supercharge American growth, it should not be afraid of stealing those playbooks, and when necessary, throwing them out.

Santi Ruiz is the senior editor at the Institute for Progress. He writes Statecraft, an interview series with policymakers about how to actually get things done.

For more coverage of the 2024 election, click here.

To support independent journalism, subscribe to The Free Press today: