The Free Press

This piece originally appeared in UnHerd.

It was autumn 2018, just over five years ago, when Christine Blasey Ford uttered that unforgettable line. “Indelible in the hippocampus is the laughter,” she said, referring to the gleeful cackling of a young Brett Kavanaugh as he allegedly drunkenly pinned her down and pawed at her clothes in an attempted assault.

This sentence turned up on protest posters, infographics, it was even stenciled across a stone threshold on the campus at Yale University. But that was then. Today, in a review of Ford’s new memoir, One Way Back, its treatment is less than reverent: The New York Times describes it as “a piece of refrigerator poetry suddenly ringing out in the wood-paneled Hart Senate Office Building.”

One Way Back is a meandering, behind-the-scenes look at Ford’s choice to come forward about the alleged assault, which she said took place at a party in 1982, when she and Kavanaugh were both teenagers. It also functions as an airing of grievances—against the politicians, lawyers, and activists who turned her trauma into a political football, but also against those journalists who promised to tell her side of the story, with inevitably disappointing results: “I’d spend hours upon hours walking them through my story. Then their book would come out, and I’d read it and feel my world turning upside down all over again.” She wrote that that experience “feels like the opposite of the justice you so desperately seek.”

Heavy on family anecdotes and ocean metaphors that serve to remind the reader that Ford is both a mother and a surfer, this memoir suggests a desire to take her story back, if not for the sake of justice, then at least for the satisfaction of having the last word. But nothing in One Way Back approaches the insight nor status of the “indelible in the hippocampus” line. Refrigerator poetry or not, this is the nature of memory: the best moments of our lives are ephemeral, slippery, like trying to capture water in your hand. And the less pleasant the memory, the more vivid it tends to be.

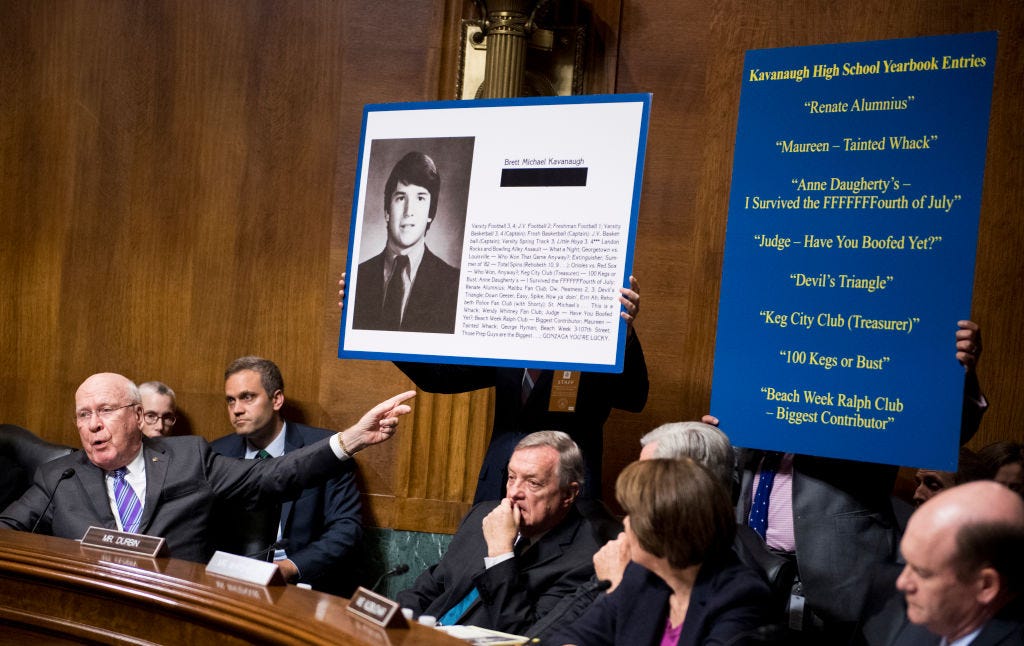

Perhaps this is why I still remember how I felt that week in 2018, as I watched Ford being replaced on the stand by an increasingly agitated Brett Kavanaugh, who blustered and wept and labored to explain the meaning of, among other things, an eighties-era joke about butt-chugging. Pages from his high school yearbook had been blown up to poster size for the occasion, like exhibits in a murder trial. It was like a cringe scene from Curb Your Enthusiasm, except without the promised relief of eventually getting to laugh. I turned to my husband.

“Christ, this is embarrassing,” I said.

“For Kavanaugh?”

“For everyone.”

Even then, it was obvious that the did-he-or-didn’t-he question would never be resolved. In my opinion, the likeliest theory remains Katie Herzog’s, that what Ford remembered as a traumatic assault was, to the men in question, more like a dumb party prank on the order of drawing a penis on your friend’s face after he falls asleep. Stupid, yes, and arguably cruel, but not the kind of thing you would necessarily remember unless you happened to be the victim. But then, the issue of Kavanaugh’s culpability was quickly eclipsed by an absolute circus of rabid frothing partisanship. On his side, there were tears, beers, conspiracy theories. On the opposing team—a unified apparatus consisting of Democratic Party politicians, the anti-Trump Resistance, and the employees of every mainstream media organization, it was a full-blown moral panic.

And if Ford’s testimony was both credible and serious, what happened next was less so. It wasn’t just the spectacle of American elected officials poring over dumb, teenage yearbook jokes as if they were unraveling the secrets of the Zodiac killer. It was that publications like The New Yorker, sensing blood in the water, relaxed their standards in order to amplify the thinly sourced allegations that Kavanaugh (or was it?) had flashed his penis (or. . . was it?) in the face of a woman at a college party, and then relaxed them yet again, this time in the service of the even more sensational, even less credible claim. It was that Kavanaugh had been seen standing in line at parties to gang rape women who had been incapacitated by drugs. Michael Avenatti—the celebrity lawyer who advanced these wilder allegations and who is now serving a 14-year prison sentence for fraud—not only became a fixture on every cable news show but was even briefly heralded as a leading Democratic candidate in the upcoming 2020 campaign to oust Donald Trump from the White House.

It was, in hindsight, a ridiculous time—but an exciting one, too, with a heady sense of possibility in the air. Even if we couldn’t ultimately derail Kavanaugh’s confirmation to the court—and maybe we could?—we could certainly spoil the moment by publicly humiliating him. Democratic politicians and media commentators alike gleefully pronounced that Kavanaugh might ascend to the court, but it would always be “with an asterisk next to his name.”

The truth, inevitably, proved more complicated. By late 2020, the anti-Kavanaugh craze was replaced with a fresh furor over the Supreme Court candidacy of the religious conservative Amy Coney Barrett. The #MeToo movement then flagged and fizzled out, amid a pandemic-era cultural reckoning that brought race, not sex, to the forefront. By 2022, when a 26-year-old man showed up at Brett Kavanaugh’s home with a plan to “save Roe v. Wade” by assassinating the justice, there was hardly a peep from Kavanaugh’s former antagonists. Being mad at Brett Kavanaugh was, like, sooooo five years ago.

This may explain today’s markedly lukewarm reception to Blasey Ford’s book—who, at the peak of her fame, was sleeping over at Oprah’s mansion, partying with Gwyneth Paltrow, and being hailed as such an icon, a modern-day folk hero, that Laura Dern would surely play her in the inevitable Hollywood biopic. Certainly, there was a time when One Way Back would have been released to celebrity endorsements, wall-to-wall-coverage, and a million-dollar marketing campaign; it would have been a seminal text of the #MeToo movement, alongside books such as She Said by Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey, or Ronan Farrow’s Catch and Kill. But these titles, released in 2019, now feel like the demarcation point of #MeToo’s steep and inevitable decline, while today, One Way Back has received only a handful of reviews, none particularly positive. The New York Times, in its dutiful assessment of the book as “important” and “lucid”, does little to obscure an overall tone of disdain; The Atlantic’s review is headlined, dryly, “Christine Blasey Ford Testifies Again.”

What little praise Ford’s effort has received is delivered with the forced cheerfulness of a person accepting a terrible hand-knitted wool sweater, in July, in a color she wouldn’t be caught dead wearing. How thoughtful of you, I. . . er, I can see you worked really hard on it.

Some will interpret this change in tone as evidence of wokeness in decline, and of a media class that lost its mind during the Trump years collectively edging back in the direction of sanity. Maybe so. But it is equally possible that this is less about the fall of a given ideology than the endless churn of the news cycle, in which every Current Thing is a national emergency until it’s replaced by the next one—where being ready to leap anew on each bandwagon is a feature, not a bug. Consider that the power of #MeToo in 2018 stemmed not from our sympathetic feelings toward victims of sexual assault, but from a sense that allegations could be used to political advantage, that even the most powerful man might be toppled if credibly accused.

Now consider the impossibility of continuing to believe this in a world in which the leading candidates for president are either the hair-sniffing, forehead-kissing, vaguely inappropriate octogenarian who once encouraged reporters to leer at a picture of his wife in a bikini—“She looks better than a Playboy bunny, doesn’t she?”—or the pussy-grabbing, porn star–bribing, thrice-married adulterer who was recently ordered to pay millions of dollars to the woman he was found legally liable for having sexually assaulted. Who, in this moment, would waste their time trying to #MeToo either of these men? Better to focus on Trump as a criminal, insurrectionist, threat to democracy; better to paint Biden not as a sex pest but a senile walking corpse. In the end, our national discourse is governed not by ideology but political expediency; the movements are a means, not an end.

Christine Blasey Ford originally emerged at the perfect time to be hailed a resistance hero: #MeToo was still ascendant, Roe had not been overturned, the battle to oust Trump from the presidency was not yet won. But that was then; the country and the conversation have moved on, and Ford’s reappearance on the public stage has not only been met without rapture, it does not even appear to be particularly welcome. Indeed, one of the most remarkable things about her testimony is how ephemeral it feels, less a watershed moment in history than an of-the-moment trend—like eighties bangs, or those pink pussy hats—which we all participated in gamely enough but now find vaguely embarrassing. Most things, it turns out, do not remain indelible in the national hippocampus; most things, once we’ve rinsed them of usefulness, we are happy to stuff down the memory hole.

Kat Rosenfield is a columnist at UnHerd and co-host of the Feminine Chaos podcast. Follow her on X @katrosenfield.

And subscribe to The Free Press for columns, investigations, debates, and more delivered to your inbox every morning:

The #MeToo movement was a beautiful idea for a minute there before it morphed into a litigious trap for wealthy men. With the decimation of women's rights and protections, the left has shown me they don't care about women. #MeToo is now #F***You. This is just more political theatre, and part of their alarmist strategy. With their pro rape laws passed, they lost all credibility on the subject of women's safety. This poor woman is just a political pawn.

This is a prime example of the Left's abandonment of due process