The Free Press

Over the past three decades, the Gender and Identity Development Service at the Tavistock Clinic in London has seen thousands of British children for gender dysphoria, with a British minister noting a more than 4,000 percent increase of referrals for girls alone in the last decade. But on Thursday, Britain’s National Health Service announced that it was closing down Tavistock for good—and, in effect, rebuking the common American medical approach known as “gender-affirming care” for treating children with gender dysphoria. This can include a mix of puberty suppressants, cross-sex hormones, and surgeries, interventions in minors that can lead to irreversible effects.

For years, whistleblowers have rang the alarm about shoddy care at Tavistock. Psychologists who worked there, like Sonia Appleby and Sue Evans, said that vulnerable children were being prematurely rushed to transition. Parents confronted the head of the clinic. A courageous detransitioned woman, Keira Bell, said that kids at Tavistock were unable to understand the ramifications of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones. The National Institute for Care and Excellence, a governmental body that creates evidence-based guidelines, found that the link between transitioning and improved psychological function was, in fact, very weak. (The oft-cited justification for childhood transition is that if gender-dysphoric kids are not allowed to transition, they will commit suicide, despite the lack of evidence for this claim.)

And then, the coup de grace: The widely respected pediatrician Dr. Hilary Cass, in an independent study of Britain’s care for transgender children, found that Tavistock’s approach was unsustainable and children were receiving inadequate care. There was, Dr. Cass wrote in her report, “a lack of consensus and open discussion about the nature of gender dysphoria and therefore about the appropriate clinical response,” among many other issues.

The National Health Service is following Cass’s recommendation to shut down Tavistock and replace it with a series of centers in regional hospitals. The bottom line: There will be no more top-down, one-size-fits-all transitioning for kids with gender dysphoria in the UK.

The question is how Americans will react.

In a sign that they may be rethinking the “puberty blockers are safe and reversible” dogma, the Food and Drug Administration, also on Thursday, announced that it was slapping a new warning on puberty blockers. It turns out they may cause brain swelling and vision loss. But for now, the move among American medical associations, health officials and dozens of gender clinics is to double down on the affirmative approach, with the Biden administration recently asserting gender affirmation is “trauma-informed care.”

The American stance is at odds with a growing consensus in the West to exercise extreme caution when it comes to transitioning young people. Uber-progressive countries like Sweden and Finland have pushed back—firmly and unapologetically—against the affirmative approach of encouraging youth transition advocated by some transgender activists and gender clinicians.

Sweden’s National Board of Health and Welfare released new guidelines for treating young people with gender dysphoria earlier this year. The new guidelines state that the risks of these “gender-affirming” medical interventions “currently outweigh the possible benefits, and that the treatments should be offered only in exceptional cases.”

Finland’s Council for Choices in Health Care (COHERE) came to a similar conclusion a year earlier, noting: “The first-line intervention for gender variance during childhood and adolescent years is psychosocial support and, as necessary, gender-explorative therapy and treatment for comorbid psychiatric disorders.” And: “In light of available evidence, gender reassignment of minors is an experimental practice.” Gender reassignment medical interventions “must be done with a great deal of caution, and no irreversible treatment should be initiated.”

Both guidelines starkly contrast with those proffered by the Illinois-based World Professional Association of Transgender Health, an advocacy group made up of activists, academics, lawyers, and healthcare providers, which has set the standard when it comes to transgender care in the United States. WPATH will soon issue new standards that lower recommended ages for blockers, hormones and surgeries. (WPATH did not respond to a request for comment.)

WPATH’s position is in keeping with an array of U.S. medical associations and activist groups across the country that insist gender-affirming care is “life-saving.” Assistant Secretary of Health Rachel Levine, who is herself a transgender woman, recently asserted that there is a medical consensus as to its benefits. Some activists and gender clinicians in the U.S. feel that WPATH doesn’t go far enough, asserting that any child who wants puberty blockers should get them, for instance, or claiming that a teenager who later regrets having her breasts removed can just get new ones.

In Sweden and Finland, this issue has been primarily a question of health and medicine. Here in the U.S. it is a political football.

This summer alone, Republican Congressman Jim Banks and Senator Tom Cotton introduced the Protecting Minors from Medical Malpractice Act, which would give minors who transitioned up to 30 years to sue for malpractice. Meantime, state legislators in California introduced a bill that would allow any child to come to California to medically transition without parental knowledge or consent. Texas had investigated parents of trans kids for child abuse if they transitioned children; earlier, other parents had been investigated, and some had lost custody of their kids, for not transitioning them.

In other words, the U.S. is engulfed by political turmoil, while the Scandinavians are not. I wondered: How had they come to their conclusions? And what can their experience teach us?

In mid-July, I spoke with Thomas Linden, director of Knowledge-Based Policy of Health Care at Sweden’s National Board of Health and Welfare. He told me that Sweden’s first guidelines for treating people under 18 with gender dysphoria came only in 2015, after increasing awareness among health care professionals of the existence and needs of gender dysphoric youth. (Adults have their own guidelines.)

“At that time, the focus was very much about the rights issues and making visible the need for care in this group and to secure access to care which was not given evenly across all over the country,” he said. Those guidelines were broadly welcomed by activist groups, patients, and the medical community, Linden said, because they were the first “to make visible the need for care in a marginalized group.” They allowed for puberty blockers and hormones, but urged clinicians to do long-term follow-up of patients who transitioned.

What they learned would lead them to shift their approach.

The 2015 guidelines were created with a certain cohort in mind. At the turn of the 21st century, the Dutch had designed a medical protocol for what was then called gender-identity disorder, based on a small group, mostly male, that had long-lasting, childhood-onset gender dysphoria and didn’t have other serious mental-health issues. They seemed to fare well after medical transition in adolescence, but the methodology asserting this wasn’t terribly reliable.

By contrast, the young people who sought care at Swedish clinics after 2015 were increasingly teenage girls with multiple psychiatric diagnoses—and there were a lot of them. “It rose from four to 77 per 100,000 inhabitants,” Linden said.“The guidelines were written for what we thought was a smaller group of patients and also more homogeneous.”

The same trend was found in Finland, where clinicians first started providing medical treatments for gender dysphoric youth in 2011. Riittakerttu Kaltiala-Heino, chief psychiatrist in the Department of Adolescent Psychiatry at Tampere University Hospital in Finland, said this came about in part over “political pressure,” as well as growing awareness that the Dutch and British were medically transitioning kids. In 2015, Kaltiala-Heino and her colleagues started to see the same dramatic increase in female adolescents with gender dysphoria. “The number of referrals skyrocketed,” she told me. “There were five-fold more girls coming in.” In addition, they seemed to not have an organic kind of gender dysphoria; rather, they “appeared to be very much influenced by other adolescents.”

According to Vogue, 2015 was the “year of trans visibility,” when Caitlin Jenner appeared on the cover of Vanity Fair, just a year after Time declared there’d been a “transgender tipping point.” It was also the year that the reality show I Am Jazz, about the trans girl Jazz Jennings, debuted.

It’s unclear if this infusion of trans storylines into the media contributed to the shift. Whatever the case, the young people showing up were nothing like the ones in the Dutch research. “We were very astonished to find out that most of the adolescents who were referred to gender-identity assessment—they had severe psychiatric problems,” Kaltiala-Heino said. Clinicians couldn’t be sure whether these problems were the cause or the effect of gender dysphoria.

This is the cohort described in Dr. Lisa Littman’s 2018 research paper, “Parent reports of adolescents and young adults perceived to show signs of a rapid onset of gender dysphoria”—a paper, and a descriptor, that activists and healthcare providers in North America have worked tirelessly to discredit. Even Littman’s employer at the time, Brown University, failed to support her. WPATH took aim at it, too. This cohort was also chronicled in Abigail Shrier’s book Irreversible Damage. Raising questions about the flood of girls seeking transition was so contentious that the book was briefly banned by Target, despite being accurately reported.

Yet countries that have tracked those seeking care—Canada, the U.K, Sweden and Finland among them—have dramatic evidence of this emerging demographic.

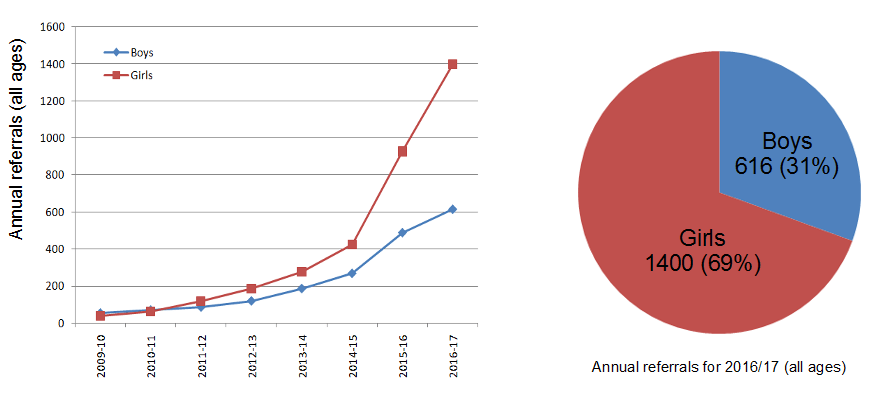

Consider this graph showing referrals to Tavistock between 2009 and 2017:

In America, the common explanation for such statistics was that they were a sign of progress—this was the natural effect destigmatizing transgender people. But for Swedish and Finish clinicians it was a cause for concern. As Kaltiala-Heino wrote in a 2018 paper, “virtually nothing is known” about adolescent-onset gender dysphoria. She worried that delaying brain maturation with puberty suppressants would stymie the adolescent task of identity consolidation, and could exacerbate existing mental-health issues. There was also a high rate of autism among those with adolescent-onset gender dysphoria.

Data was one thing. The other major shift that occurred was the increasing visibility of detransitioners.

Because the Dutch study had indicated that relatively few patients regretted having transitioned, many clinicians assumed that detransitioning—reverting back to living as one’s birth sex—was rare. But in Finland, clinicians started to see more young people regretting medical transition, Kaltiala-Heino said. “Regrets are not coming immediately,” she said. “It’s after four, five years, maybe.” One study showed that 76% of detransitioners didn’t inform their clinics of any feelings of dissatisfaction or regret, so it was difficult to calculate the actual rate of detransition. Some regretters felt rushed into treatment or realized later they were gay and gender nonconforming, and shouldn’t have changed their bodies. A recent study in the U.K. showed a 10% detransition rate.

“We have a great blind spot there in that we don’t know how many actually there are,” Linden, from Sweden’s NBHW, said about destransitioners, adding that he thinks the phenomenon is more common than previously thought. Sweden’s guidelines noted that the existence of detransitioners revealed that “gender-confirming treatment thus may lead to a deteriorating of health and quality of life (i.e. harm).”

In the U.S., on the other hand, aside from a segment on 60 Minutes, the mainstream media almost completely ignored detransitioners, with activist groups and even media outlets arguing that it was too dangerous to air their stories, because that might affect access to medical interventions and fuel Republican legislative attempts to delay transition until adulthood.

Meanwhile, there was growing concern in Sweden and Finland about gender-affirming treatments. Doctors were worried about intervening “in the completely healthy and functioning body,” Kaltiala-Heino said, when research on impacts on bone health or metabolic influence or sexual function haven’t been fully researched. As Finland’s COHERE’s recommendations noted about puberty blockers: “Potential risks of GnRH therapy include disruption in bone mineralization and the as yet unknown effects on the central nervous system.” They added that, in trans girls, “early pubertal suppression inhibits penile growth, requiring the use of alternative sources of tissue grafts for a potential future vaginoplasty.” And: “The effect of pubertal suppression and cross-sex hormones on fertility is not yet known.”

“Individual doctors were under great pressure,” Kaltiala-Heino said. Therefore, “we asked this national body to evaluate this situation and create national guidelines.”

COHERE began with a systematic review, conducted by a panel of neutral experts, of the literature on the safety and efficacy of treatments. The panel found that even studies of adult patients were of such low quality that it was impossible to claim medical and surgical reassignment improved psychiatric problems. And studies of children didn’t clearly assert a correlation between medical interventions and improved mental function. After the evidence review, Kaltiala-Heino’s team finished a paper that found that cross-sex hormones did not improve problems related to “functioning, progression of developmental tasks of adolescence, and psychiatric symptoms.”

“Scientific evidence for any interventions on minors with gender identity indication is actually zero,” Kaltiala-Heino told me. That is, there are some studies that show improvement from interventions, but they are of such a low quality that they can’t be relied on to tell us anything important about the wider population. In particular, a Dutch follow-up study often cited as evidence for early hormonal interventions actually compared people who already had good mental health, other than dysphoria, to a group whose mental health was so poor they were deemed ineligible for early intervention. Yet that excluded group with worse mental health was also doing somewhat better at follow-up. Other studies were small, or had short follow-ups, and none had been replicated.

Sweden’s findings were similar. Both guidelines suggest therapy as the first-line treatment for gender dysphoria. “We continue to lack really reliable scientific evidence concerning the efficacy and safety,” Linden said about medical transition. “We have to have better knowledge. There was really no way to properly assess risk without more and better evidence.” In both countries, medical interventions for gender dysphoria are not banned, or completely discontinued. “It’s not stopping all treatments,” Linden said. It just means limiting puberty blockers and hormone treatment to “exceptional cases.”

In Finland, for patients who fit the profile of participants in the Dutch study, after a prolonged period of evaluation, and with a multidisciplinary team including a psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker and nurse, puberty blockers may be started near the onset of puberty, and cross-sex hormones may be possible starting at age 16. Assessments take place at two gender identity clinics; gender surgeries are offered only at one center. Both Finland and Sweden now stress gathering data and extensive follow-up.

Why, when we have the same explosion of teenage girls with complex mental health issues seeking treatment and the same low-quality evidence, is America not following Sweden’s and Finland’s direction? In the United States, there has been only one nonpartisan evidence review, commissioned by the Florida Agency for Health Care Administration, earlier this summer. It, too, found “insufficient evidence that sex reassignment through medical intervention is a safe and effective treatment for gender dysphoria.” This report got almost no media coverage, even though some of the low-quality evidence it noted had been written up in major publications as “proof” that cross-sex hormones and puberty blockers decrease the risk of suicide.

Perhaps our own blind spot comes from not having a national, nonpartisan group to create guidelines, and relying on groups like WPATH to do that work. The closest thing we have is a governmental organization called the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which found: “There is a lack of current evidence-based guidance for care of children and adolescents who identify as transgender regarding the benefits and harms of pubertal suppression, medical affirmation with hormone therapy, and surgical affirmation.” Yet many of our medical advocacy organizations, like the American Academy of Pediatrics, promote the affirmative model of care. And that group has been accused of suppressing dissent and refusing to conduct a nonpartisan evidence review, despite pediatricians requesting it.

What we have is a culture war. Specifically, we have lots of battles playing out in legislatures and courts, which could go on for years. All the while, we are not conducting long-term research or following up with young patients. We have no idea how many kids are transitioning, how well they are faring, and whether or not they will come to regret it.

Linden and Kaltiala-Heino both say the new guidelines, in Sweden and Finland, did not drop without controversy. “Of course there are people who are not satisfied,” said Kaltiala-Heino. But among the clinicians working with gender dysphoric youth, “We find these national guidelines appropriate because the evidence base is so weak.”

“Our standpoint is that this is a medical treatment, you cannot go into a clinic and order it,” Linden said. “You have to be assessed for your needs and have to be informed of the risks.” In contrast, here in the states, some doctors advertise surgeries to children on TikTok.

America is increasingly becoming an outlier among Western countries in failing to demand better evidence for the consequences of irreversible youth gender transition. In the meantime, it can look to the closure of Tavistock for an example of prioritizing evidence over politics, listening to voices of concern and dissent, and working toward a sane and humane solution for an ongoing and difficult problem.

Gender affirming care therapy is a crime? Mutilating bodies of confused young pre-pubescent girls? Telling them there is no other way to come to terms with their bodies during puberty.

The TikTok gender doctor deserves the Bin Laden treatment. Just erase her from existence.