The Free Press

Kai Micah Mills is going to freeze his parents.

“They’re both going to be cryopreserved, regardless of their wishes,” Mills told me.

Don’t worry, he’s told them. “Even my dad has been pretty open to it. Most Mormons are really just transhumanists.”

Transhumanists believe that cutting-edge technologies can help us augment our minds and our bodies to transcend the human condition. Mills identifies as one, though he adds, “I think a new term is needed.”

The 24-year-old’s dirty blond hair, which reaches his mid-back, flowed down and out of the video chat window when we talked a few weeks ago. (He has a scruffy blond beard, too.) He was talking to me from Salt Lake City, Utah, sitting in his bright white house with exposed steel beams and a flat-screen TV set to a video of a bonfire—an eternal, if synthetic, flame. He’s talking low and slow. He’s not in much of a rush. Along with his parents and two sisters, he’s planning on living forever.

Last year, Mills launched the company Cryopets, which aims to use cryogenic technology to preserve freshly deceased animals, and eventually humans, forever—or until someone comes up with a cure for whatever killed them, in which case they’ll be thawed, healed, and set loose for a Second Coming.

His first guinea pig is an 80-pound labradoodle named Jasper, who is 16 and has a degenerating spine and hips. In the next few months, Jasper will be euthanized. Then, his blood will be drained and replaced with a medical grade antifreeze in order to preserve his cells. “Ice crystals are the enemy” for destroying body tissue, Mills tells me. Jasper will get loaded into a low-pressurized dewar, a vacuum-sealed vessel, that will be kept indefinitely at negative 196 degrees Celsius using liquid nitrogen, as a sort of Schrodinger’s dog. At first, Jasper will be stored in Mills’ garage—“I covered the windows in there, it’s a little intense for the neighbors”—until he transitions his cryogenic equipment to a larger, temperature-controlled facility next month.

The whole thing will cost Jasper’s parents—who found Mills on Facebook— around $30,000.

“That’s less than a year of cancer treatments or whatever, which might give them one or two more years, and that’s if it works,” said Mills.

The practice of cryonics has been around since the 1950s, when sperm was first frozen, then thawed and used to inseminate a woman. Now, up to 2 percent of births in the U.S. are the result of a similar vitrification process.

But while IVF has been successful for birth, the process has yet to produce results on the other side of the coin. The academic Robert Ettinger first posited the idea of cryopreserving humans in his 1962 book The Prospect of Immortality, and a long-running rumor has it that Walt Disney, or at least his head, was frozen upon his death (he was actually cremated and interred in a family mausoleum). But not a single human has ever been revived after being frozen.

Currently, about 500 people are in a state of suspended animation, including Ettinger, his first and second wives, and his mother, mostly in U.S. facilities. The Ettingers are frozen in suspended animation in Clinton, Michigan, and another popular facility—a sort of techno-optimist’s cemetery—is outside of Scottsdale, Arizona. In the history of medicine, only a few life forms have been frozen and then reanimated, including the Bdelloid rotifer and the tardigrade, or water bear, a sturdy eight-legged micro-animal that was brought back in 2015 after 30 years on ice, and then later, had babies.

“It’s the only technology that directly targets death,” Mills told me, referring to cryonics. “We obviously need a way to put biology on pause, and put people in stasis until we can solve every single cause of death, which is going to take time.” He is not just referring to killers like cancer and heart diseases, but accidents and homicides, too.

In order for all this to succeed, we will eventually need solutions that go beyond our biology, Mills said. A crumbling hip will be replaced with an AI-powered joint, for example, or one’s consciousness will be uploaded to the cloud.

Deciding that death is just another coding error has become something of a Silicon Valley bar mitzvah of late—when you reach a certain age and net worth, it’s time to start figuring out how to live forever. Being really rich is no longer about owning a helipad or an impressive art collection; it’s about creating a facility in which scientists fashion a future where you can meet your great-great-great-great-great-grandchildren.

Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI and previously the president of start-up incubator Y Combinator, has sunk $180 million in Retro Biosciences, which seeks to extend the human lifespan by 10 years. Jeff Bezos has invested in Altos Labs, which has $3 billion in the bank and works toward cellular rejuvenation to “reverse disease, injury, and the disabilities that can occur throughout life.” Google founder Larry Page’s immortality outfit is called Calico, with a charge to “enable people to live longer and healthier lives.” The CEO of Coinbase, Brian Armstrong, founded NewLimit (they’re “inventing medicines composed of epigenetic reprogramming factors that restore youthful function in old cells”), and he just raised $40 million to put toward it.

The billionaire investor Peter Thiel (PayPal, Palantir) is destined for his own frozen fate. He’s signed up to be preserved through the Alcor Life Extension Foundation upon his demise, but sees it as more of a social statement. (“I’m not convinced it works,” he recently said on The Free Press’s podcast, Honestly. “It’s more, I think we need to be trying these things.”)

In many ways, we live in an age when moonshots abound. The future we’ve always imagined, or maybe feared, feels eerily present. Existential game-changers that once seemed to linger in the distance, like interplanetary colonization, or AI singularity, or gene editing, are now creeping into view.

And yet, for most of us, even as Elon Musk’s rockets take off from Texas to Mars, all of that still seems like science fiction. Tech progress often feels more like Facetune or the latest iPhone iOS update. What Mills and his cohort are suggesting is that we look up from Candy Crush and aim higher. Like the highest.

Mills, who grew up Mormon but has since left the faith, was 16 when he sold his first company, MyMCServers, a platform that hosts video game servers for Minecraft and Team Fortress 2. He’s also part of the latest batch of Thiel Fellows, who are awarded $100,000 over two years to pursue their start-ups through Thiel’s foundation, provided the grantees drop out of college or skip it altogether—which isn’t a problem for Mills, who left high school at 14.

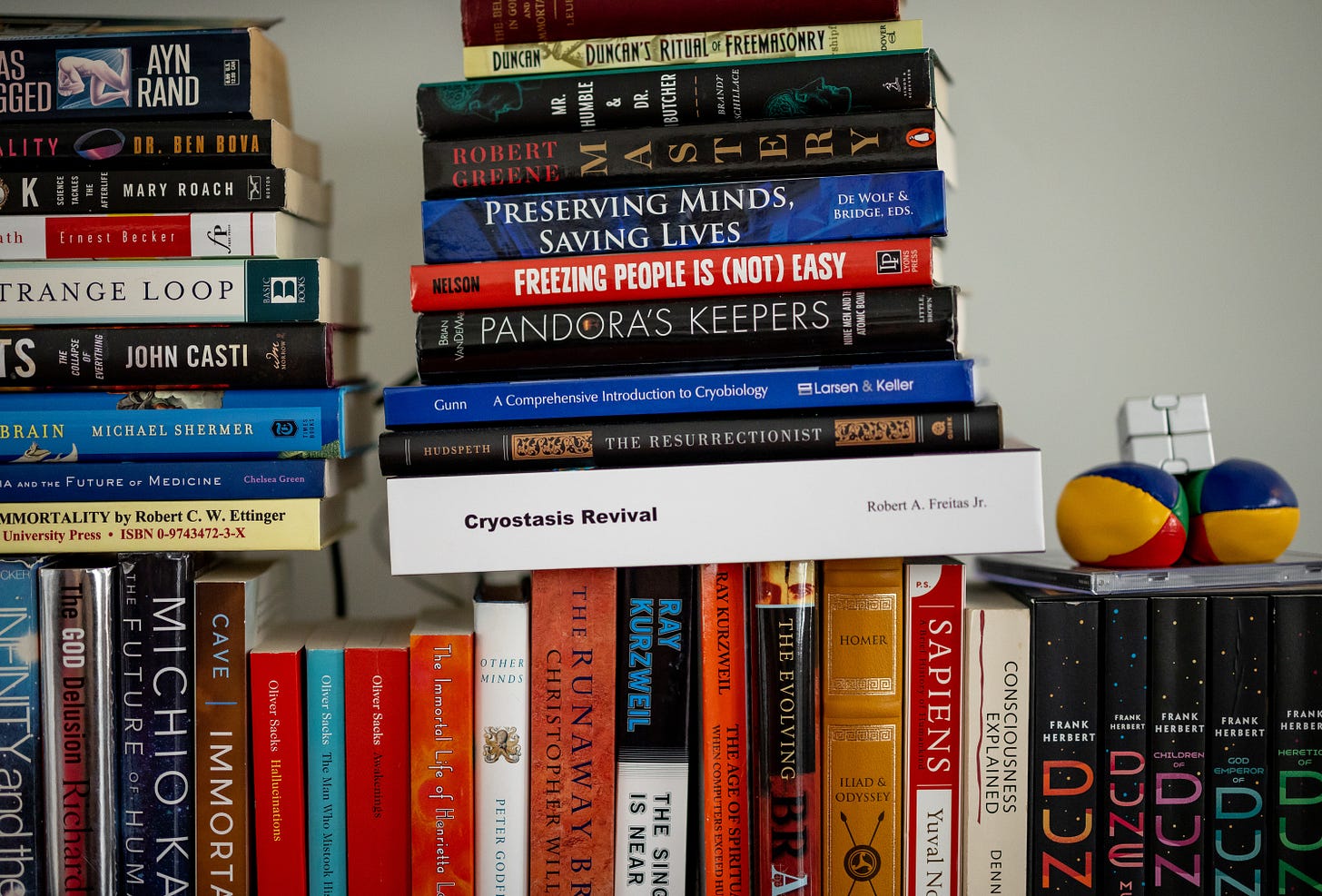

“I was definitely a cocky teenager,” he explains, “and I just didn’t want anyone else’s opinions.” He only read his first book at the age of 21, The Future of Humanity by Michio Kaku.

I wondered what Mills’ idea of an infinite future might look like. Like The Matrix? Groundhog Day? Later, I texted him: What will you do if you live forever? What’s on the top of your list?

He texted me back: Living forever = eternal progression, we should become gods and create for eternity.

Ben Lamm, 41, calls himself an “eternal optimist.” Which is important, given that he’s trying to pry open Pandora’s Box. Lamm is the founder of Colossal Biosciences, the Texas biotech start-up that aims to unleash woolly mammoths back on Earth by 2027. He also has plans to revive apex predators like the Tasmanian tiger, which went extinct in 1936, and the (hopefully less ferocious) dodo bird.

Part of Colossal's charge, and the larger de-extinction movement, is to “rewild” the environment, and reintroduce “lost animal species into their natural environments.”

The de-extinction business is no longer the stuff of Hollywood fantasy. Four years ago, another outfit, Ginkgo Bioworks in Boston, brought back prehistoric scents from long-dead plants, including the mountain hibiscus, a Hawaiian native that disappeared from the face of the earth in 1912.

Lamm’s cofounder is George Church, who is also Colossal’s lead scientist and an early pioneer of the CRISPR gene editing tool, the innovation that won two other scientists the Nobel Prize in 2020. At some point, Lamm and Church also plan on selling the de-extincting tools they create, such as artificial wombs, to hospitals and governments.

On living forever, Lamm told me via video chat from Dallas, where Colossal is based, “I would like to be here as long as possible, because I think there’s a lot of hard things to do and interesting things to learn.” He added: “If you want to live to 1,000 and beyond, and it doesn’t hurt other people, you should be able to.”

It worries him that when our brightest minds die, it’s difficult—and sometimes even impossible—for others to pick up their work. He describes this problem in computing terms, using the phrase “context switching,” which details how a computer processor loses productivity when it switches from one task to another.

“I think there’s context switching in death. We see it in software and in other technologies, and it’s not free,” said Lamm. “Let’s say you had an expert that achieved that level of expertise at age 85, and that person could live to 160. You know, that’s 75 years more of a nod of progress on a problem.” So: Centuries of Einstein or Mozart. Or Mussolini. Or an everlasting ruling class made up of Boomers who refuse to die.

The real-world pitfalls of a society of forever-aging humans—overcrowding, pollution, or Xi Jingping ruling China for 2,000 more years—don’t seem to trouble Lamm.

“There will always be nefarious actors who want to leverage technologies in evil ways,” he said. Now that we have arrived at this point, Lamm added, “You just can’t put the genie back in the bottle.”

“I generally think that humanity’s going to figure things out.”

Mills and Lamm think it would be cool to live forever, but their ideas are anathema to many, including Simone and Malcolm Collins.

The Collinses are the leaders of the American branch of the pro-natalist movement, which believes it is our moral imperative to have as many kids as possible to combat cratering birth rates. Another pro-natalist is Elon Musk, who has so far fathered ten kids among three different women, and has criticized the pitfalls of living forever, recently tweeting, “I can’t think of a worse curse.”

“There is a growing divide in the Silicon Valley diaspora between the life extensionist faction and the pro-natalists,” Malcolm Collins told me over the phone from their Audubon, Pennsylvania, farmhouse. The couple, who are in their 30s, do not procreate in the old-fashioned way. Instead, they create embryos then choose which specimens to bring to life. They currently have three kids and are aiming for somewhere between 7 and 13 in total. They have 29 embryos in the freezer.

The Collinses believe that we’re in the “endgame” for two reasons. First, because fertility rates are so low, they believe the stakes of having children are much higher. Your offspring can actually steer the course of civilization, they argue. They also believe we’re close to reaching longevity escape velocity or LEV, in which medical advances are happening so quickly that they increase people’s life expectancy faster than the years that go by.

They tell me that the drive to live forever is a “disgusting philosophy.” (Right now, their youngest child, a girl called Titan Invictus, is on the call too, babbling away.)

“We already have a gerontocracy that’s causing toxic discrepancies in power,” said Simone, of our world run by old people—from 80-year-old Joe Biden to King Charles III, who was crowned this month at 74, to our senators, whose median age is 65.3.

Malcolm, in his rapid-fire cadence, agrees. “People who want to live forever believe they are the epitome of centuries of human cultural and biological evolution. They don’t think they can make kids that are better than them.”

The Collins family is secular, but their ideas are echoed by Jay Kim, the pastor at WestGate Church in San Jose, California, who serves the Silicon Valley area—and a lot of tech workers from Google, and at Apple, which has a campus down the road in Cupertino.

“In the digital age we’re losing humility,” Kim tells me over the phone. “Maybe we’re not losing curiosity as much, but we are losing wonder. Instead we see everything as a problem to be solved, and as an equation to be figured out, including death.”

He calls death “a natural part of the human process,” and told me that trying to use science to achieve immortality feels like “arrogance.”

Between the extremes are the biohackers, who are trying to live, if not forever, then for as long as possible using a buffet of infusions, supplements, injections, ultrasounds, tinctures, exercise routines, scans, custom diets, creams, colonoscopies, MRIs, heart rate monitors, fasts, detoxes, saunas, plunges, and lasers that carry with them the promise of a few more trips around the sun.

Thomas Ivers, a 63-year-old I spoke to who lives in Naperville, Illinois, takes forty vitamin supplements and pills in the morning, ten in the afternoon, and another forty to fifty at night. He’s considered taking rapamycin, an immunosuppressant drug given to organ transplant recipients, to stave off aging. “If I can make it to 90, I think they’ll have a mechanism to download the brain, with our memories and thought patterns, which I’d definitely be interested in,” Ivers told me.

Another biohacker is Allison Duettmann, who is 32 “in her current chronological age,” but according to her epigenetic clock—which assesses a person’s biological age based on their DNA molecules—she is closer to 27 or 28. Dutemann, the CEO of the Foresight Institute, a nonprofit that supports far-out tech like space exploration and neurotechnology, works out every day. She also has plans to be frozen upon her death. “There are policies that are relatively inexpensive the earlier you start,” she told me.

But the big dog in the biohacking space is Blueprint CEO Bryan Johnson, a 45-year-old entrepreneur and venture capitalist, who spends $2 million a year to reverse his own aging process. “I’m trying to prove that self-harm and decay are not inevitable,” Johnson told Bloomberg, adding that his methods, which aim to turn back time on each of his organs, is “a new frontier.”

But, when I bring up Johnson, Mills seethes: “He’s not reversing his aging process at all.”

Mills dismisses the longevity-obsessed, like Johnson, as “people who care about vanity.” Living a longer, healthier life is a fine goal, he told me, but not one shared by him. “I want to solve the death problem.” Anything else just misses the point.

But life—and death—can be random. The oldest living human is María Branyas Morera, 116, who says her marathon existence is owed to “Luck and good genetics.” Jeanne Calment, a French woman who lived to 122 and died last year, only decided to give up cigarettes at the age of 117. Anyone, no matter what tinctures they put in their coffee, can get taken out by an anvil falling from a window.

Even so, there are a few basic guidelines to longer life. Peter Attia, a doctor and an expert on longevity, has noticed that a lot of people he meets who want to maximize their lives are so focused on never dying—or so convinced immortality will happen before their own bodies give out—they aren’t taking care of their current cholesterol or blood pressure numbers.

“I’ve spent a decade studying this problem, and from a technical perspective, there’s just nothing that comes close to exercising when it comes to living ten years longer,” Attia, author of the new book Outlive, told me.

Attia doesn’t think super-long lifespans are coming anytime soon. “People who think they’re going to live for 300 years fundamentally don’t understand biology,” he said. We don’t understand our own psyches either. As we age and live longer than ever, our fundamental purpose changes, too.

“For 99 percent of human history, the only thing you needed to accomplish was reproduction and getting your offspring to reproductive age. That’s all Darwin asked of you,” Attia said. “Now I think Darwin would ask more of you, as far as what you impart on your offspring, and the world.”

And, as for what we can control, so much is still unknown.

“There’s something sad and beautiful about how relatively short our lives are,” Attia added. “If that was gone, I wonder how we would spend our time. It takes away some urgency.”

If we ever do reach immortality, the journey there will be filled with even bigger concerns and conundrums.

Like: As the capability of medicine goes beyond just healing what’s broken, what should we use medicine for? And, if you come back at a different time, shaped by a different culture, and without any of the relationships of the people you were born around, is it even worth it? And, for now, does having the lung capacity of an 18-year-old actually make someone 18 years old, or 43 and with too much time on his hands?

In the end, Pastor Jay Kim believes he will live forever—and he doesn’t need cryonics or any other cutting-edge science to do it.

“As a Christian, I believe in eternal life more than most,” he said. “I do think I will live forever. I just don’t think the path to that is paved with ones and zeros, and technology and medical advancement.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story misstated that Kai Micah Mills dropped out of high school at 16. In fact, he dropped out at the age of 14. —TFP

Suzy Weiss is a reporter at The Free Press. Read her piece about the surrogacy boom here.

And to support more of our work, become a Free Press subscriber today:

And Jeanne Calment died in 1997, at 122, being born in 1875.

Death is the greatest of all equalizers; no one can elude it, no matter how blessed in life. Take that away and you will have either the greatest differentiator between the haves (those who can pay for extended life) and the have-nots, or the mother of all entitlement programs.

Also, it is foolish to assume that longer life equals greater productivity. Death is the proverbial “shot clock” that forces people to score before time runs out. Take away the clock and humanity will slide into despair and suicide as we fritter away the hours that are no longer precious.