At The Spence School, a tony all-girls private institution on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, Anne Protopappas was larger than life. “Bonjour!” she’d smile to students, wearing her quintessentially French red lipstick with Plato tucked under one arm and croissants in the other to offer her next class.

For a quarter of a century, generations of young Spence women adored our “Madame Proto.” She spearheaded school trips to China and Japan, launched a language and culture institute, revived the Model United Nations Club, advised the yearbook staff, developed a debate team, and offered special “salon” classes to parents and alumnae. Part Vietnamese, part Greek, and part French, she speaks five languages. When I was at Spence from 2006 to 2019, there was no teacher I admired more. She was the only faculty member in the language department to receive three yearbook dedications and four recorded money donations to the school in her name.

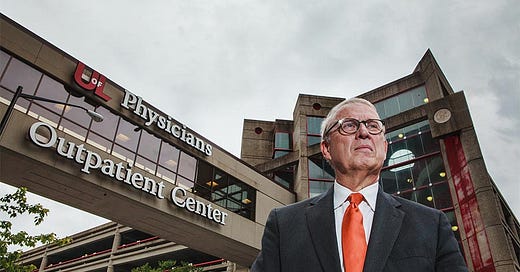

But in February, she was fired. Unable to find another teaching job, she is suing the school, its trustees, and its two top officials, Head of School Felicia Wilks and Director of Teaching and Learning Eric Zahler. In the lawsuit, filed earlier this month in New York State Supreme Court, Protopappas and her attorney, Sean Dweck, claim she was the victim of “employment discrimination based upon age, race/national origin” and “retaliation after lodging complaints about the discriminatory practices at the school.” What’s more, they argue, after a student took issue with the way Protopappas, 62, conducted a class, Spence deprived her of the due process that would have allowed her to defend herself.

“I never thought that I would pay such a high price for practicing and teaching the skill of free and responsible expression and independence of mind at a school that I picked for its open-mindedness twenty-five years ago,” Protopappas told me. “I have done nothing but serve this school.”

Protopappas’s firing stems from a May 2023 incident that took place in her Advanced French class, which was being taken by eight Spence seniors. Out of the blue, according to the complaint, one student asked, “Why did France ban the hijab?”

Protopappas said she responded by thanking the student and then giving the class some background about why the French law banning hijabs and all other visible religious symbols in public K-12 schools was in accordance with the country’s belief in secularism, or laïcité. She said she invited the class to consider the pros and cons of this law, which came into being after a nationwide debate in which some Muslim women advocated to protect young students from family pressures to wear the veil.

According to Protopappas’s complaint, the student who had asked the question, Sarai Wilks, “unexpectedly burst out of anger and displayed an uncharacteristically emotional and intensely personal reaction to the discussion, focusing on how unfair the French law was to her friend from her former school on the West Coast who wore the hijab.”

Sarai is not just any student. She is the daughter of the head of school, Felicia Wilks, who began her tenure in July 2022. The next day, Sarai returned to class—the last day of her senior year—and “expressed even more anger, as if she had been inflamed,” according to the complaint. “She also tried but failed to get her peers involved and join in her outrage. She was very disappointed to be unsuccessful and to remain isolated in her anger. Her classmates were embarrassed and confused by what seemed completely out of the ordinary and blown out of proportion, especially since Sarai and her West Coast friend became the focus of the two final days of a productive year they had enjoyed.” (Free Press requests for comment from Sarai Wilks were not returned.)

It was all downhill from there. Protopappas scheduled meetings with administrators to discuss Wilks’s reaction in class, but the meetings were canceled and postponed, the lawsuit claims. According to an email shared with The Free Press, when she finally met with Zahler, the director of teaching and learning, he told her that “some students” found her comments regarding the hijab “Islamophobic.”

“Overnight, I felt demonized, discredited, disqualified, and delegitimized,” said Protopappas.

The following school year, Protopappas’s Advanced French class was placed under “scrutiny,” her complaint says. She proposed two interdisciplinary courses, on “Trust, Truth, Faith & Facts” and on “Identities in Exile,” the sort of courses that had always been approved in the past. Wilks said no to both. While in the past Protopappas had taught the philosophies of “the dead white men”—including Jean-Paul Sartre, Blaise Pascal, René Descartes, and Immanuel Kant—she had also introduced students to the influence of the Harlem Renaissance on France’s Negritude, a literary movement of French-speaking black intellectuals. She explored how the Arab and Christian worlds coalesced in French culture.

And yet, by February, Zahler had concluded from three visits to her class that her teaching was “inequitable, confused students, and prevented them from speaking in class” and “did not meet Spence’s standards and expectations,” according to the complaint. Despite two decades of student evaluations in which she was lauded as “by far Spence’s best asset,” according to a PDF of the appraisals she shared with me, Protopappas was brought into an in-person meeting with Wilks and the school’s head of human resources and informed of her termination.

“It’s Orwellian,” Protopappas told me.