MAYVILLE, New York — Two and a half years after nearly losing his life outside this remote lakeside town, Salman Rushdie squared off against his accused assailant in a snowbound courthouse Tuesday morning.

In meticulous detail, the Booker Prize–winning author testified about the maniacal knife assault he endured while onstage at an arts festival on August 12, 2022. The attack—and he was stabbed 15 times before Good Samaritans in the audience subdued his assailant—left Rushdie’s then–75-year-old body punctured from his throat to his liver.

“It occurred to me, quite clearly, that I was dying,” the British American novelist methodically told the 16-person jury made up of rural New Yorkers. His alleged attacker, Lebanese American boxing enthusiast Hadi Matar, 27, sat impassively across from him, clad in a baggy, light blue dress shirt and oversized trousers. “And that was my predominant thought,” Rushdie added.

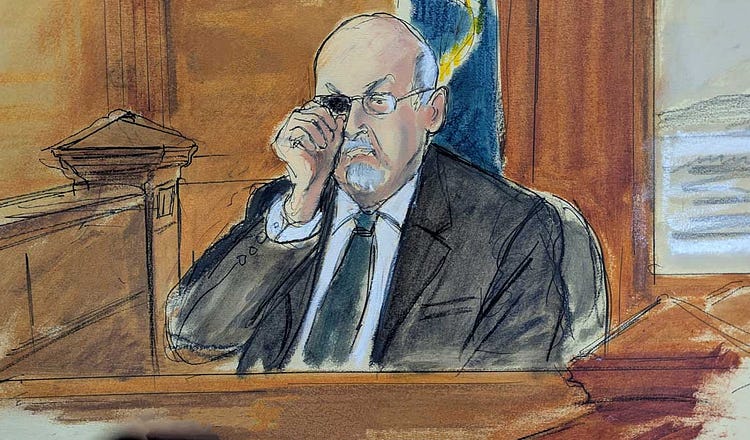

The stabbing cost Rushdie partial use of his left hand, along with his right eye. He wears a special pair of glasses, with a darkened lens covering the missing eye. At a dramatic high point of his testimony, Rushdie removed the spectacles to show the jury members exactly “what’s left.”

“It was a stab wound in my eye, intensely painful, after that I was screaming,” the Indian-born writer said. “A lake of blood, that was clearly my own blood. . . was spreading outwards.”