The Free Press

The last time an American president faced a serious primary challenge, the Soviet Union still existed, Roseanne was the No. 1 sitcom in the country, and Mark Zuckerberg was seven years old.

That was December 1991, when right-wing populist Pat Buchanan launched his bid to wrest the GOP nomination from President George H. W. Bush.

Buchanan didn’t get far, but he left Bush mortally wounded, and the president—who had successfully faced down Saddam Hussein in Kuwait and helped America end the Cold War—ultimately lost to Bill Clinton.

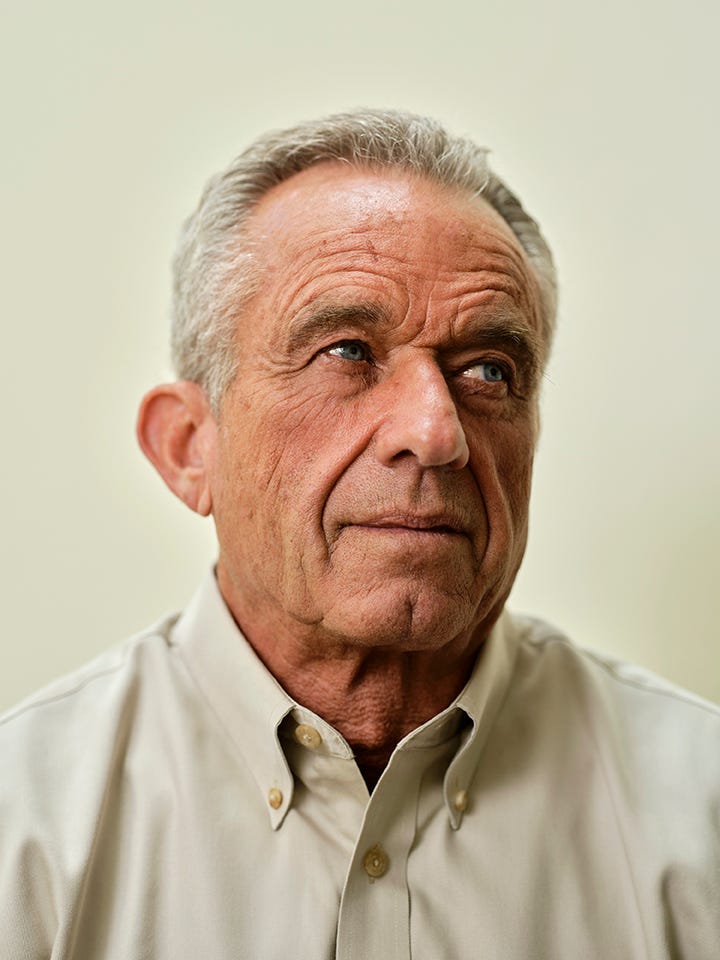

That’s the dynamic Joe Biden is up against today, with Robert F. Kennedy Jr.—the environmental lawyer, vaccine skeptic, and scion of the Kennedy dynasty—challenging the president in the Democratic primary. So is best-selling author and former self-help guru Marianne Williamson.

The most recent CNN poll shows Kennedy winning one in five voters; Williamson, 8 percent; and another 8 percent of Democrats supporting “someone else.” On top of that, according to the same poll, Biden’s favorable ratings have been slipping: 42 percent of all voters had a positive view of him in December; today, it’s 35 percent. He’s been underwater, with more voters disapproving than approving of his administration, since late August 2021.

Part of that is Biden’s age. Sixty-two percent of voters, including more than a third of Democrats, worry about the mental fitness of the president, now 80 and apparently unable to get through a press conference without a cheat sheet.

But the real reason Biden is hemorrhaging voters, Kennedy said when we met at his home in the hills on the west side of Los Angeles, isn’t the president’s age or acuity but something deeper.

“I’ve always liked Joe Biden,” Kennedy told me.

The problem, he explained, is that Biden is a function of a system that a growing majority of Americans don’t trust. “I see him doing things that I know, at his core, he cannot possibly believe in—the censorship that’s coming out of the White House, it’s so contrary to everything that he’s stood for over his life.”

He was referring to the White House and Facebook working hand in hand to root out “problematic posts,” as former White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki had put it. But he could have been talking about Twitter. Or Google. Or the synergy—or is it collusion?—between the most powerful technology companies and the American government.

RFK Jr. likes to talk about “Big Tech,” “Big Pharma,” “Big Media.” A decade ago, when liberals were still hostile to supposedly greedy, publicly traded companies, that kind of language would have resonated on the left. Today, with many of those same companies implementing the DEI-ESG-Covid regime championed by progressive elites, the left seems mostly at home with corporate America—and any talk of Big This or Big That sounds conspiratorial.

But consider Kennedy’s experience on Theo Von’s podcast This Past Weekend.

In November 2020, Von, a comedian whose YouTube channel has more than 1.7 million subscribers, interviewed Kennedy, and they discussed what was then the new Pfizer Covid vaccine. Von posted a series of clips with Kennedy on This Past Weekend’s YouTube channel, and for two and a half years anyone could watch them.

That is, until a little over a week ago, when YouTube, according to people at the company and the comedian himself, pulled them from Von’s page.

Von told me he’d contacted YouTube to find out what had happened—why a few videos that hadn’t raised any eyebrows at YouTube for two and a half years suddenly disappeared a month after Kennedy announced his presidential bid.

He was informed that Kennedy had violated the site’s medical misinformation policy. Among Kennedy’s more provocative assertions were the claims that, when it comes to the Covid vaccine, “the press is utterly captured,” and “all of the other institutions of government that should stand between a greedy corporation and a vulnerable child have been compromised.” There was, as with so many of Kennedy’s claims, an element of truth—legacy media has been very quick to buy whatever the Biden administration is selling—mixed with a great deal of vagueness and insinuation.

Von added that YouTube made it clear to him that, if he published other clips that violated YouTube’s medical misinformation policy, his videos would be demonetized, or he might be shoved off the platform.

If you’re YouTube, these are the basic rules of the road—how else is the platform supposed to prevent the spread of bad information during a pandemic? But if you’re RFK Jr., this is evidence of our broken system—and the timing is suspicious. “If you’re a media platform, you know, you should be questioning the government,” Kennedy said. What’s happening now, he added, “is kind of the opposite. Instead of speaking truth to power, they’re broadcasting propaganda to the powerless.”

Kennedy’s house is plastered with ivy and built in the Spanish style. When I arrived, there was a guard outside with an earpiece and a nondisclosure agreement, and when I said I couldn’t sign, an assistant came out, and he seemed a little miffed. A moment later Kennedy came out, shrugged, and led me inside.

There’s a feeling you’re supposed to feel when you enter the house—the old idealism, the sense of boundlessness: The signed black-and-white image of him and his uncle, President John F. Kennedy; the photo of his father, Robert F. Kennedy; the framed, oversized, 15-cent stamp with his father’s likeness; the two-story entrance, capacious and full of light; the artwork (including a painting of him and his wife, the actress Cheryl Hines, which was a gift from the artist, the Brazilian Romero Britto); the floor-to-ceiling bookshelves; the big, floppy dogs; the stocked bar.

It would not have seemed strange for a gaggle of strapping young men to be playing touch football in the backyard.

And then there’s the man himself, with his sleeves rolled up, rugged, handsome, with the firm grip, the raspy voice. At 69, he looks like he has years of fight left in him.

It felt like America picking up where it had left off just past midnight on June 5, 1968, nearly 55 years ago to the day, when the candidate’s father, Robert F. Kennedy, the former attorney general, senator, and a leading contender for the Democratic White House nomination, was murdered about ten miles east of here, in the now-razed Ambassador Hotel. That night, he had scored two big primary wins, and it seemed as though there might be a chance for the party, and America, to piece itself back together, to transcend the division and crisis of Vietnam, race riots, and the counterculture.

“My father, on the last day of his life, won the most rural state in our country and the most urban state—he won South Dakota and California at the same time—and so he succeeded in kind of bridging the gap between Americans who were divided,” Kennedy told me.

And then RFK was gone—murdered by Sirhan Sirhan, the 24-year-old Palestinian American who hated Kennedy’s views on Israel and confessed at his trial. (RFK Jr. doesn’t believe the official story. He thinks the CIA probably killed RFK and definitely killed JFK.) The Democratic Convention in Chicago, two months later, was a disaster. In November of that year, the Republican nominee, Richard Nixon, won the White House.

Kennedy recalls his father, on the campaign trail, talking about Latin America and the coming revolution, and saying that someone was going to harness that anger—a communist, perhaps, or someone else, someone better.

“That same thing is true in this country today,” he said. “There are people who are angry, and they deserve to be angry, and either Trump is going to sign them up, Donald Trump, for a ride into the darkness, or we can try to capture that energy and turn it into something positive for our country, something that is reflective of the highest ideals of the American experience.”

I asked what that looked like.

“It’s basically building a coalition of the left and the right—a populist coalition,” Kennedy said. There were dangers in that, he conceded. “Populism is easy to hijack. Demagogues can easily hijack it by exploiting humanity’s negative, universal impulses: greed, anger, hatred, bigotry, self-pity, xenophobia, misogyny.” That was the danger of Trump.

“But also, you know, a lot of populist movements are idealistic in their core,” he said. “My father was a populist, but he was appealing to something better, those parts of ourselves that say we have to step outside of our narrow self-interest and see ourselves as part of a community and resist this seduction of the notion that we can advance ourselves as a people by leaving our poorer brothers and sisters behind.”

To be clear, Kennedy will probably lose big. He lacks money and voters, and it’s unclear which, if any, major Democratic constituencies or donors—unions, trial lawyers, public school teachers, George Soros, Michael Bloomberg—would back him. (“A big chunk of his base is Republican obviously,” one Bay Area supporter, a former Silicon Valley executive, texted me.)

Kennedy’s No. 1 liability is his crusade against vaccines—both the Covid vaccine and vaccines more generally. To his detractors, it’s proof that he is beyond the pale. But to his supporters, it’s an asset—it shows the candidate is willing to take on what he calls “the biosecurity state.”

Ninety percent of Democrats have been vaccinated against Covid. Kennedy insists the Covid vaccines have “overwhelming safety and efficacy problems.” During the pandemic, he published a book—The Real Anthony Fauci: Bill Gates, Big Pharma, and the Global War on Democracy and Public Health—and compared America under the Covid lockdown to Nazi Germany. “Even in Hitler’s Germany, you could cross the Alps to Switzerland,” he said. “You could hide in an attic like Anne Frank did.” That prompted his wife, Cheryl Hines, to issue a statement calling his remarks “reprehensible and insensitive.” (Hines is sticking by her husband. She introduced him at his campaign announcement before he delivered a nearly two-hour speech.)

Kennedy’s opposition to the Covid shot is an extension of his broader vaccine skepticism. He is adamant that the increase in the number of vaccinations schoolchildren were required to get, starting in the late 1980s, caused an increase in several serious disorders, including eczema and peanut allergies. When I asked him whether vaccines were to blame for the uptick in childhood autism, as he had previously contended, he replied: “Absolutely, there is a link.”

There is zero scientific evidence to back this up. The 1998 article in the journal Lancet that first posited a link between vaccines and autism has been debunked and retracted. (Krystal Ball of Breaking Points, in a recent interview with Kennedy, suggested he was confusing correlation with causation.)

Other White House candidates have vociferously opposed Covid lockdowns and blanket vaccine mandates. Governor Ron DeSantis is pitching himself as the guy who kept Florida open while the rest of the country went crazy. But DeSantis has not voiced skepticism about routine vaccines, as RFK Jr. regularly does.

All of this made it difficult for the Kennedy supporters I spoke to to go public with their support.

Until Covid, anti-vaxxers were a little likelier to be progressive than conservative. But now, with Covid, it’s right-wingers who are more likely to be anti-vax than left-wingers. (Such is the power of our tribalization.) Which explains why Kennedy’s supporters fear coming out of the proverbial closet and alienating their more mainstream Democratic friends and colleagues. I asked Kennedy what he thought of that, and he laughed and said: “I suppose I’m disreputable.”

And yet, these liberals and progressives wax poetic about the general election campaign he’d run—“He’d easily beat Trump,” one of them told me. “It would be so unifying,” another promised. If he could only leapfrog the primaries, they muse. Which is impossible. Because democracy.

What they are expressing is profound dissatisfaction with the state of their party, with its leadership, and with its current standard-bearer. They see a Democratic establishment that increasingly resembles the Republican establishment of 2016: sclerotic, insular, and incapable of grappling with the most pressing issues of the day, like crime, inflation, immigration, and government corruption.

“The Democratic leadership establishment hijacked the party,” Marianne Williamson told me. Williamson ran in the Democratic presidential primary the last time round, and few took her seriously. She was a healer of souls, and she sounded like it. “The real you is not a body,” she tweeted in January 2016. “Your body is merely a suit of clothes. Physical birth was not your beginning and physical death is not your end.” Still, it was Williamson who uttered perhaps the most memorable and truest words of the whole race, when she talked of a “dark, psychic force” in America today.

Williamson averaged less than 1 percent in the polls in 2020, but that didn’t stop her from running again. In March, a month before RFK Jr. got in the race, she announced her second White House bid. “It’s a very different Democratic Party than I grew up with,” Williamson, 70, told me. “We’re like a ship listing so far to one side at this point that we need fundamental economic reform in order to achieve even the minimum of a level playing field. That’s how much damage has been done over the last 48 years—the entire paradigm of trickle-down, vulture capitalism, the $50 trillion transfer of wealth upwards.”

A former Democratic congressman who did not want to be named and is supporting Kennedy said that, among seasoned Democrats, “there’s a concern” about what’s happening to the party, “but it’s almost like that which is not to be talked about. The people who are pros, they know there’s a reckoning coming.” A recent survey showed Donald Trump, who was impeached twice and found liable for sexual assault earlier this month, beating Biden by seven points.

Elected officials, bundlers, lobbyists, legacy media—these people are not about to dump Biden. They figure he defeated Trump once. He can do it again. Polls go up and down. They have plenty of time to pump a few hundred million more dollars into the race.

The problem with that kind of thinking, Williamson said, is that it doesn’t take into account the moment we’re in.

“The country feels different now,” she said. “We thought it was critically important to defeat Trump in 2020, and of course, it was. But there was also a naive belief that, if we just did that, the country might go back to normal. Clearly, the problem was bigger than one man. There’s a hatred, a neo-authoritarianism that had already metastasized. I’m convinced that a transactional politics alone, one that fails to address the underlying dynamics of what’s happening in this country, will not be enough to win in 2024.”

So is Kennedy.

“It’s become a war party,” Kennedy said of the Democrats. “It’s become the party of the neocons. It’s become the party of Wall Street and the party of censorship, which, I think, was, you know, antithetical to liberal values.” The worst part, he said, was that Democrats, who were supposed to be the aspirational party, the party of idealism and possibility, had become the party of fear. “We’re supposed to be the party that tells people that the only thing to fear is fear itself.”

The Democratic higher-ups had become untethered from reality. That was Williamson’s take. “In 2016, two political candidates said to the American people, ‘I see your suffering, and I validate your rage’—Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders,” she said. “Hillary had the attitude of ‘Let’s continue the success of the last eight years,’ and there were millions of Americans who said, ‘What success, lady? I’m dying here.’ ” After a moment, Williamson added: “I fear that that same delusion and denial is alive today.”

It’s not an accident that Williamson, who spent much of her last campaign calling for a “moral and spiritual awakening,” is now summoning the senator from Vermont, talking about “the war on the poor and the middle class,” and demanding universal healthcare, guaranteed sick leave, and an end to college debt.

“Democratic politics today is a politics that says, ‘I will try to help you survive within an unjust system,’ ” she said. “What I’m saying is the Democratic Party should end the unjust system.” She wants to return the Democrats to their liberal roots: Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the social safety net, the party of Main Street, the people drowning in the postindustrial gig economy.

I asked Williamson what she thought of President Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris. “They’re lovely people,” she emailed me. “If the Democrats are serious about winning in 2024, however, I don’t feel they’re the ticket that can do that.”

There is, on the left and right, an emerging economic-populist consensus. “There is a realignment that has occurred,” Dennis Kucinich, the former Democratic congressman and presidential candidate now managing the Kennedy campaign, told me from his home in Cleveland. “It hasn’t been identified and articulated yet, but it’s absolutely happening.”

David Kochel, a Republican media consultant who advised Mitt Romney’s 2012 campaign, said, referring to Kennedy: “I have a number of folks in my DMs talking about how they agree with 90 percent of what he says.”

“Both parties have a segment that fit naturally together and do not care about divisive issues,” Allan Stevo, the author of The Case for Robert Kennedy and The Bitcoin Manifesto, told me from his home in San Francisco. Stevo is backing Kennedy in the Democratic primary—he attended a recent fundraiser for him in Palo Alto. “There’s sort of a survival instinct kicking in, because things look too dire to fight. Trump and Kennedy both address the needs of those people.”

An RFK Jr. supporter in Hollywood, who feared professional and social backlash if he spoke openly, messaged me: “I’ll never vote Dem again, unless it’s Bobby.” Referring to the journalist Matt Taibbi, who, like The Free Press, angered many Democrats with his reporting on the Twitter Files, he said: “These people want to arrest Taibbi”—an allusion to Rep. Stacey Plaskett’s April 13 letter to Taibbi suggesting his reporting could land him in prison. “Their science is shit, and they’re war-mongering, racially- and gender-obsessed lunatics at this point. It’s madness.”

He added: “Not voting for Trump, I just won’t vote.”

The whole Covid experience—the dissembling about where it came from, the lockdowns, the vaccine, the vaccine mandate—just exacerbated or accelerated fears and processes that had been put in motion decades ago, Kennedy told me.

“I think it’s the same kind of forces that have been dominant in this country since my uncle’s assassination,” he explained, referring to JFK. He meant what Dwight Eisenhower, in his famous 1960 farewell address, had called the “military-industrial complex,” which not only included weapons and weapons manufacturers but, Kennedy noted, “the federal science bureaucracy.”

“It’s all the same now. You know, I think they really, officially came together with the biosecurity agenda in 2001, after the anthrax attacks, when the military really found common cause with the medical bureaucracy,” he said.

He went on—about the Patriot Act, the rise in biological weapons spending, the confluence of government and industrial “forces.”

I asked him how many vaccines were in his body. He said that, years ago, he’d had batteries of more than 20 vaccines at a time (“more than most”), recalling his many trips to Africa.

“I’m not anti-vaccine,” Kennedy said. “I’m against any medicine that’s improperly tested.” Dr. Vinay Prasad, a hematologist-oncologist at the University of California–San Francisco, who has been highly critical of public health officials’ handling of Covid, said in an email, “I think the original 2020 approval was fairly tested. Properly even.”

Democrats active in fundraising circles I spoke to—the kind of people who have seen Biden give his stump speech while crowded around an infinity pool in the Palisades, or squeezed into a well-appointed living room on Central Park West—were quick to dismiss RFK Jr. They saw him as a vanity candidate, a spoiler exploiting Democrats’ apparently unslakable thirst for all things Camelot.

“Kennedy is Connor Roy—lucky to get 1%” a Democratic fundraiser in Los Angeles, who did not want to be named, texted me—referring to the eldest son on HBO’s Succession, who wages his own quixotic battle for the presidency.

The thing is, 20 percent in the polls isn’t quixotic. The confusion and sense of loss on the left—the people mystified by the mask mandates and the party’s coziness with big pharmaceutical and tech companies—that is real. It is percolating across the country. And just as it upended right-wing norms and expectations, it will upend the whole progressive project. It will redefine it.

When I asked Kennedy how he thinks his father or uncle would have responded to the many challenges facing the Democrats and the United States, he was vague.

“You know,” he said, “I have conversations with my father and my uncle about what I’m doing. I do meditations every day, and that’s kind of the nature of my meditations. I have a lot of conversations with dead people.”

In a follow-up text, he clarified: “They are one way prayers for strength and wisdom. I get no strategic advice from the dead.”

Peter Savodnik is a writer and editor for The Free Press. Read his work here.

We’d love to know what you think of RFK Jr. and Marianne Williamson. Do their campaigns speak to something deep about our moment? Or are they distractions? Let’s talk about it in the comments.

And to support more of our work, become a Free Press subscriber today.

Listen to what RFK Jr is saying rather than what is being said about what he is saying! Hard to disagree on a lot of topics if really listening!!

Great insights into Robert Fitzgerald Kennedy Jr., the candidate and the man.