The Free Press

You have to figure that after the helicopter crashed into it last Wednesday, American Eagle flight 5342’s passengers had maybe two seconds of knowing what was happening before the plane hit the water and broke into pieces. To my mind, they were lucky. When the outer starboard engine of the United DC-8 my dad was flying home cut another passenger plane—a TWA Super Constellation—in half over Staten Island, it took 90 seconds for my dad’s plane to fall to earth. An excruciating minute and a half.

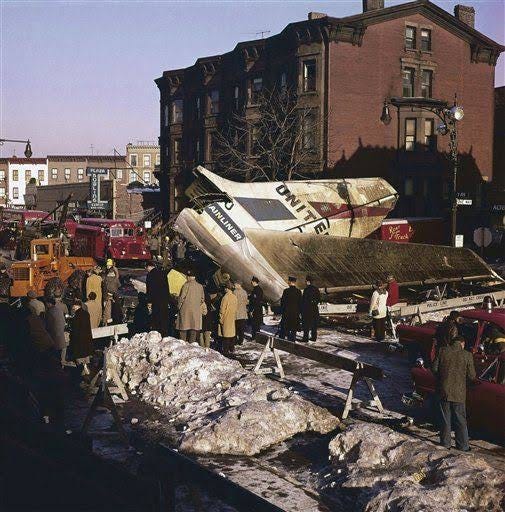

It was December 16, 1960, nine days before Christmas. The DC-8 my father was in still had one engine and one wing, and the pilot tried desperately to land it in Prospect Park. But he came up short, falling into the Park Slope neighborhood of Brooklyn and hitting the Pillar of Fire Church and McCallan Funeral Home before breaking into pieces. Eighty-three of the 84 passengers died on impact. An 11-year-old boy was thrown into a snowbank, but died the next day. All 38 people on the TWA plane also died, as well as six people on the ground.

There were also no survivors when the American Eagle plane crashed into a UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter over the Potomac River in Washington. We don’t yet know the cause of the deadliest disaster of its kind of the past 25 years, but that hasn’t stopped endless speculation that it has to do with everything from DEI, a technical glitch, understaffing, or having too much faith in government agencies.

The National Transportation Safety Board will conduct an investigation, and recreate the moments leading up to the crash. Both aircraft black boxes will be pored over. Eventually, we will know what happened in the air and on the ground in those horrible seconds. A few of us also know what happens next for the survivors. It’s a small club.

I was 7 when my dad died. It was snowing in Bronxville and I had stayed home from school. Washing the breakfast dishes, my mother said, “I hope your father’s plane is okay in this snow.” When I answered the doorbell later that morning, my father’s secretary was at the front door in a thick winter coat. I’d never seen her outside of the Custom-Made Paper Bag factory in Long Island City.

Before she could say anything, I said, “Is he in the hospital?” All these years later, I’m certain that the quote is word-for-word accurate because when a kid’s father just disappears forever, in an instant, his brain takes a snapshot for posterity. I can still taste the lasagna someone brought over, and how it had too much spinach.

But as things settled down, we became not just photos in the paper but a little worse: In the perfect village of Bronxville, my mother, my two brothers, and I were a scar of a family. A Shirley Jackson lottery loser. We moved to Manhattan five years later, but not out of the dark place we found ourselves. The Sumerians of seven thousand years ago were unusual as a civilization for thinking that the afterlife wasn’t an improvement on this life, just a huge, eternally dim-dark vault with ashes in very distant corners. That is as good a description of where we plane-crash people go as I’ve ever come across. That is where I went for a very long time. Those 90 seconds. He was my dad. How could I not think about what happened in those 90 seconds?

Some deaths are easy to absorb, if no less tragic—the ones from disease, or battle—but plane-collision deaths aren’t. People glance at the pictures, at the bios of the dead, but just for a moment before sprinting back to their own whole, clean, and well-lit dimension. They leave you stuck in that same old dark corridor with everyone else in the club of people who loved someone who had died for the stupidest of reasons, in pieces of flying aluminum tubes designed to get us somewhere faster.

When you tell someone your dad died in a plane crash, the instant expression that crosses their face is unconstrained by censors: It’s a look of abject, pre-thought horror, an expression that no actor, no matter how talented, could ever authentically convey. That’s how scary and alien our world is, our exclusive club.

For whatever reason, despite flying for work for several decades, over vast oceans or into tiny airfields, I never developed a fear of flying. I’d always wanted to write, and when people began to pay me to do so as a reporter, I became intimately acquainted with what seemed like hundreds of airports. Maybe I was counting on the lightning-striking-twice thing.

Plane crashes always include pieces of bodies. Once, in 1982, I had to cover one as a reporter. I was in New Orleans reporting that wind shear pushed a Boeing 727 down when it tried to take off. It cartwheeled and broke apart in some fields. Being the intrepid reporter, I sneaked around a police barrier in the dark and walked into a floodlit “debris” field where the location of body parts was marked by small yellow flags. Afterward, I threw my shoes away.

In 1944, my father led a thousand-man battalion of Marines as they assaulted caves dug into the coral and full of Japanese soldiers on the island of Peleliu, which no one you’ve ever known could find on a globe. By the end of the war, he’d won two medals by leading charges that someone of his high rank wasn’t required to. One of his men told me later that they all thought he had a horseshoe up his ass; that’s how lucky he always was.

Then, 16 years later he died at 44 with a wife and three kids. He was coming back from Chicago on a trip to sell his company’s paper bags. The day before he boarded United 826, he’d exchanged tickets with a friend so that he could get on the earlier doomed plane to get home to lead an Eagle Scout troop meeting. My older brother was in his troop. My father’s luck ran out trying to get back to his family.

The circumstances of my father’s death were detailed 11 months later, when the National Transportation Safety Board issued its 68-page report. One machine and two humans—one on the ground, one in the cockpit—had screwed up at the same time. When the crash happened, it was huge news; in New York City, the collective grief about the collision dwarfed everything. But when the report was published, it went largely unnoticed. By then people had lost interest in the plane crash. Except of course my family, and the families of the other 127 people who died in the crash.

My mother wouldn’t let me go to the funeral, even with a closed casket. I know his body was intact, because one of the Marines he fought with randomly happened to see his body in the Kings County morgue that day. “My god!” he said. “That’s Major Richmond!” She also refused the Marine Corps’ offer of burying him at Arlington. She later told me it was because she wouldn’t have been able to handle the rifle salute.

When I think about what happened in that plane during those 90 seconds, I imagine my dad, hoping and maybe even trusting that the pilot will somehow pull off the impossible. I imagine him reassuring the other passengers and telling them what to do, the way he would have commanded his Marines in battle: Stay calm, it’s going to be okay. I’ll obviously never know, but that’s what I imagine.

TWA 266, the plane that the DC-8 hit, carried the title Star of Sicily. My father’s jet had been called Mainliner Will Rogers. At the dawn of the passenger jet age, United had been flying DC-8s for only thirteen months, and the names of planes were more important then.

No one has said anything about the name of the American Eagle plane that crashed last week. But we do know a little about the people who died—they included seven buddies, including James “Tommy” Clagett and Charlie McDaniel, who were returning from a duck-hunting expedition in Kansas; Grace Maxwell, a university student returning to school after attending her grandfather’s funeral; a beloved figure skating coach, Alexandr “Sasha” Kirsanov, and more than two dozen skaters returning from a big competition in Wichita. I’m here to tell you that when people fall from the sky, it has importance. To the club—and to its newest members, the families of the 67 who perished last week: We veterans of the club are reminded all over again. When people fall out of the sky and die, we in the club do too.

Peter Richmond is a New York Times best-selling author. Among his books are My Father's War: A Son’s Journey.