The Free Press

Peggy Noonan wrote speeches for Ronald Reagan. She helped get George H. W. Bush elected. She’s consulted on The West Wing. And she’s been a weekly columnist for The Wall Street Journal for nearly a quarter of a century, writing columns that have won her a Pulitzer—and have now been partially collected in a forthcoming book called A Certain Idea of America.

“What is that idea?” Peggy writes in the excerpt we’re publishing today. “That she is good. That she has value. That from birth she was something new in the history of man, a step forward, an advancement.” After a week of doomerism about our democracy, we thought our readers deserved to read her hopeful words about what she describes as “our continuing miracle, America.”

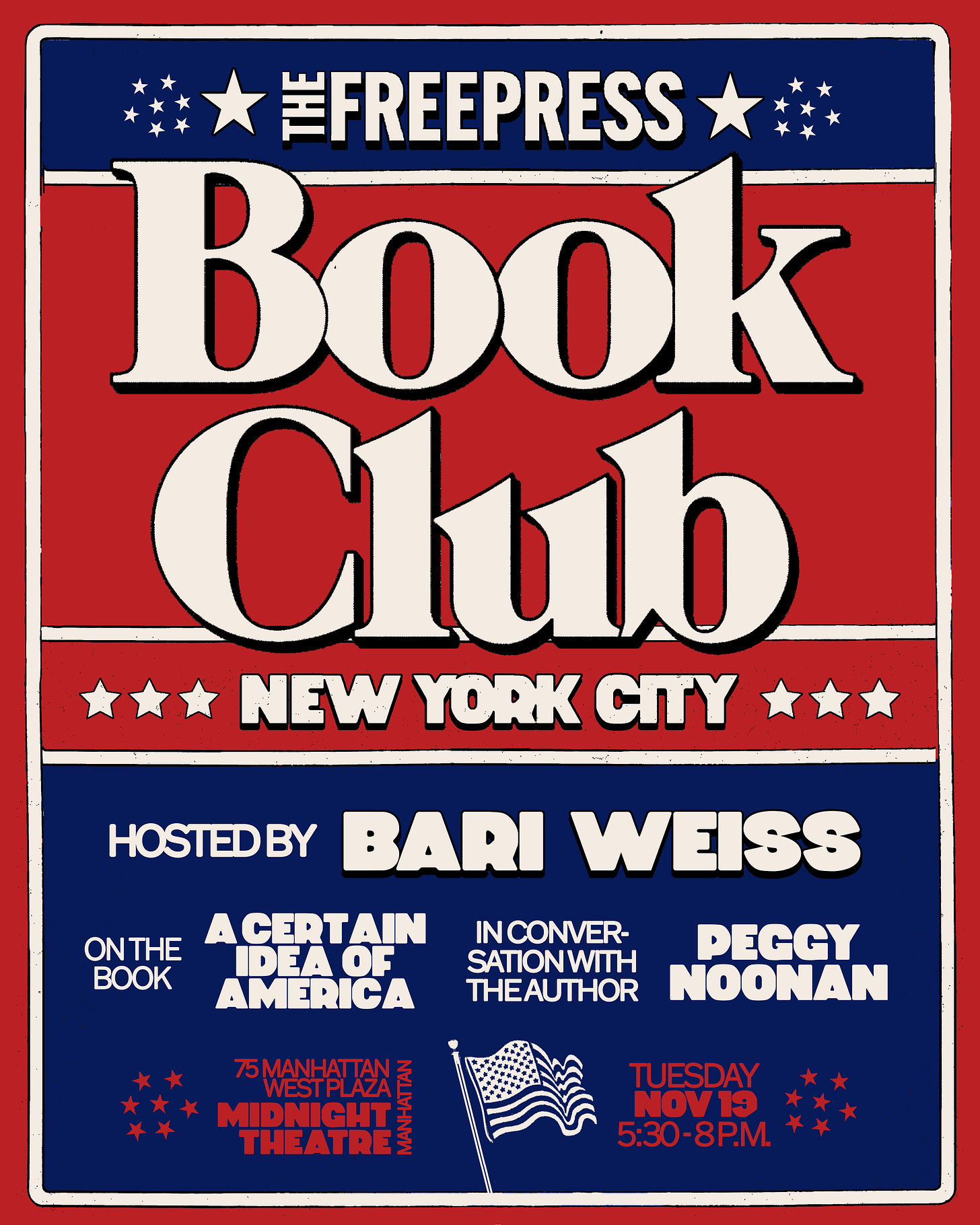

From the power-hungriness of Joe Biden to the magic of Taylor Swift and, yes, the insanity of Donald Trump, A Certain Idea of America examines the most powerful forces that have shaped our nation over the last decade. It’s out November 19, and we’re thrilled to announce that Peggy has chosen to spend publication day with us, as our next Free Press Book Club guest. Bari Weiss will be hosting in New York City—and you’re all invited. There’s going to be an open bar. What are you waiting for? We’re expecting this one to sell out fast, so reserve your ticket now by clicking here.

But first: Peggy’s essay. Part of the aim of The Free Press Book Club is to reflect on older books that speak to new ones, and in this piece, Peggy recommends three that, she writes, “touch on the why, how, and what of loving America.” We hope you love reading about them as much as we did. —The Editors

The famous first sentence of Charles de Gaulle’s War Memoirs most happily translates as: “All my life I have had a certain idea of France.” It struck me when I first read it many years ago and stayed with me because all my life I have had a certain idea of America.

What is that idea? That she is good. That she has value. That from birth she was something new in the history of man, a step forward, an advancement. Its founders were engaged in the highest form of human achievement, stating assumptions and creating arrangements whereby life could be made more: just. In the workings of its history, I saw something fabled. The genius cluster of the Founders, for instance: How did it happen that those particular people came together at that particular moment with exactly the right, different but complementary gifts? Long ago I asked the historian David McCullough if he ever wondered about this. He said yes, and the only explanation he could come up with was: “Providence.” That is where my mind settles, too.

De Gaulle said his thoughts on France were driven as much by emotion as reason, and it is the same for me. I’m not really big on purple mountain majesties. I’d love America if it were a hole in the ground, though yes, it’s beautiful. I don’t love it only because it’s “an idea.” That strikes me as a little bloodless. Baseball didn’t come from an idea, it came from us—a long cool game punctuated by moments of high excellence and utter heartbreak, a team sport in which each player operates on his own. The great movie about America’s pastime isn’t called Field of Ideas, it’s called Field of Dreams. And the scene that makes every grown-up weep is when the dark-haired young catcher steps out of the cornfield and walks toward Kevin Costner, who suddenly realizes, That’s my father.

The great question comes from the father: “Is this Heaven?”

The great answer: “It’s Iowa.”

Which gets me closer to my feelings on patriotism. We are a people that has experienced something epic together. We were given this brilliant, beautiful thing, this new arrangement, a political invention based on the astounding assumption that we are all equal, that where you start doesn’t dictate where you wind up. We’ve kept it going, father to son, mother to daughter, down the generations, inspired by the excellence, and in spite of the heartbreak. Whatever was happening, depression or war, we held high the meaning and forged forward. We’ve respected and protected the Constitution. And in the forging through and the holding high we’ve created a history, traditions, a way of existing together.

It’s all a miracle. I love America because it’s where the miracle is.

In celebration of that miracle: Three books that touch on the why, how, and what of loving America.

1. On Democracy, by E.B. White

Start with E.B. White on why.

America should be loved, tenderly, for a large and obvious reason: because it is a democracy. In July 1943, at the height of World War II, White tried to define what that means. “Democracy is the recurrent suspicion that more than half of the people are right more than half of the time,” he wrote in The New Yorker. “It is the feeling of privacy in the voting booths, the feeling of communion in the libraries, the feeling of vitality everywhere. Democracy is a letter to the editor. Democracy is the score at the beginning of the ninth. It is an idea which hasn’t been disproved yet, a song the words of which have not gone bad.”

This short essay, “The Meaning of Democracy,” is included in a recent collection of White’s work, On Democracy. In the introduction, Jon Meacham notes that Franklin D. Roosevelt loved White’s words. One of his speechwriters recalled that FDR read the essay aloud at gatherings, in his unplaceably patrician accent, often adding a homey coda at the end: “Them’s my sentiments exactly.”

There’s a lot of sweetness in this collection.

2. What So Proudly We Hail, edited by Amy and Leon Kass and Diana Schaub

Here’s an argument on how to love America.

There was a young man in 1838, an aspiring politician almost too shy to admit his ambition to himself or others, who gave a talk to a Midwestern youth group. It was a speech about public policy, but it showed a delicate appreciation of psychology, of how people feel about what’s happening around them.

America’s Founders—“the patriots of ’76,” this aspiring politician called them—were now all gone, James Madison having died 19 months before. In their absence Americans felt lost. Those men stood for this country, they modeled what it was in their behavior. Admiration for them had united the country. Now, without them, people felt on their own. First principles were being forgotten, mob rule was rising. In Mississippi, they were hanging gamblers even though gambling was legal. It was madness, and it threatened the republic.

The aspiring politician had an answer. Transfer reverence for the Founders to reverence for the laws they devised. “Let reverence for the laws,” he said, “become the political religion of the Nation.” Let all agree that to violate the law “is to trample on the blood of his father.”

You have already guessed the speaker was Abraham Lincoln, then only 28. He was addressing the Young Men’s Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois. This speech is a small part of a stupendous compilation of the best things said by and to Americans called What So Proudly We Hail. Its diverse contributors include Philip Roth, Ben Franklin, Willa Cather, and W.E.B. Du Bois. My friend Joel, an America-loving New York intellectual, gave me the book as a gift. He opens it every night at random and always finds something valuable. Now so do I.

As I read, I thought of those who today oppose illegal immigration. They are often accused of small and parochial motivations. But I believe at the heart of their opposition is a delicate understanding that when the rule of law collapses, as it does daily on the southern border, everything else can collapse. Many things are more delicate than we think, and those most inclined to see that delicacy are most dependent on responsible leaders who will keep the laws of the nation strong and operable.

3. The Pioneers, by David McCullough

Now, quickly, on what you love when you love America.

Twenty years ago the historian David McCullough was asked to be commencement speaker at the 200th anniversary of Ohio University. In researching the school’s background and the area’s history, he came upon a rich trove of stories of the largely unknown Americans who in 1788 went to the Northwest Territory and settled “the Ohio.”

The speech set him on the road to publishing, 15 years later, a book. The Pioneers is about the remarkable New Englanders who went to Ohio and insisted from the beginning that in this unknown America there would be absolute freedom of religion, that there would be a major emphasis on public education, and that slavery would be against the law.

It is an inspiring story; harrowing, too. They suffered and caused some suffering, too. And yet, McCullough notes, historians would see that the ordinance that allowed the pioneers into Ohio “was designed to guarantee what would one day be known as the American way of life.”

To read it is to feel wonder at all the sacrifice that went to the making of: us. And our continuing miracle, America. With all her harrowing flaws—we have always been a violent country, for instance—she deserves from us a feeling of profound protectiveness. Our great job as citizens is to shine it up a little, make it better, and hand it on, safely, to the generation that follows, and ask them to shine it up and hand it on.

Peggy Noonan is a columnist at The Wall Street Journal, where a version of this essay originally appeared. Follow her on X @PeggyNoonanNYC, and preorder A Certain Idea of America today.

This is an edited excerpt from A Certain Idea of America: Selected Writings by Peggy Noonan, to be published November 19, 2024, by Portfolio, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright 2024 by Peggy Noonan.