The Free Press

My finest memory of Pope Francis is from January 2015, when I watched him celebrate Mass in Tacloban, in the eastern Philippines. Wearing a disposable rain poncho over his vestments, as the winds of a tropical storm battered the outdoor altar, he preached to survivors of the 2013 Typhoon Yolanda.

The congregation listened, many of them in tears, as Francis commiserated with them over their loss of homes and loved ones. He said he could not fault them if the ordeal had cost them their faith and admitted he could offer no other comfort than the Cross. “But I see Him there nailed to the cross,” he said, pointing to a crucifix. “And from there, He does not disappoint us.”

That sermon was Pope Francis at his best, displaying his well-known compassion for the downtrodden but also a grave, even somber, side that he showed less often. He was best known, worldwide, for his cheerful, thumbs-up persona, especially when greeting children, but he seemed more deeply himself that day.

I have been covering the Vatican since 2007, a span that includes Francis’s entire pontificate—which began with his election on March 13, 2013, and ended with his death on Easter Monday at the age of 88, mere hours after he appeared for a final time in St. Peter’s Square on Easter Sunday.

That day in Tacloban, he displayed his flair for the dramatic gesture, a quality in which he rivaled his charismatic predecessor, the former actor St. John Paul II. He did the same in March 2021, when much of the world was shut down by the pandemic, and Francis insisted on traveling to, of all places, Iraq.

For the Vatican press corps, it was an irresistible story—and a chance to receive one of the first Covid-19 vaccines courtesy of the Holy See—though those of us with little experience reporting from war zones had our qualms. Both Vatican officials and local Iraqi clergy had hoped the pope would delay his trip, for both security and public health reasons. Indeed, Francis later revealed that authorities had foiled plans to assassinate him during his stop in Mosul, where he spoke among the ruins of the city battered by the Islamic State. The large gatherings of the faithful may have been reckless from an epidemiological standpoint, but they were a shot in the arm for beleaguered Iraqi Christians, whose numbers had been steadily dwindling.

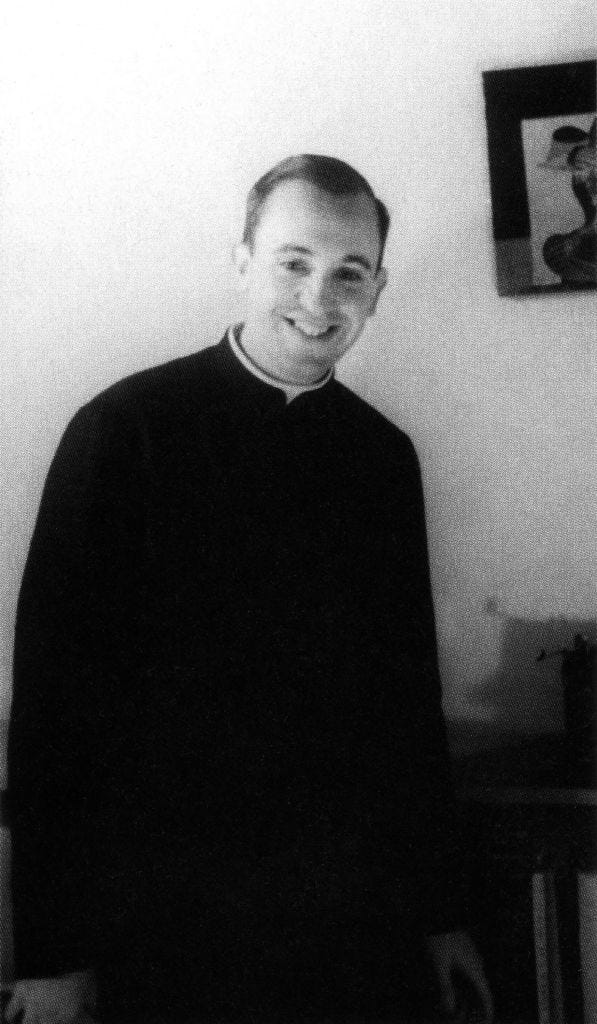

Francis’s solidarity with the marginalized was not only spiritual but also highly political. Born in 1936 to a family of Italian immigrants in Argentina, Jorge Mario Bergoglio was, in his youth, a supporter of Argentina’s populist strongman Juan Perón, a persistent and influential challenger to U.S. influence in Latin America. After joining the Jesuit order as a young man, Francis quickly rose in the ranks, becoming head of the order in Argentina at just 36. He proved controversial in that role. “My authoritarian and quick manner of making decisions led me to have serious problems and to be accused of being ultraconservative,” he later recalled of that period.

Nevertheless, he continued to show leadership qualities, and Pope John Paul II made him archbishop of Buenos Aires in 1998 and elevated him to the rank of cardinal three years later. Runner-up in the 2005 conclave that elected Pope Benedict XVI, who resigned eight years later, Bergoglio was elected his successor and became the first pontiff to take the name Francis, after the mendicant saint from Assisi. The new pope, who had been known for his work in the shantytowns of Buenos Aires, told reporters a few days later that he sought to lead “a church which is poor and for the poor.”

That same year, he published an agenda-setting document, Evangelii Gaudium, in which he denounced a capitalist economy governed by “the laws of competition and the survival of the fittest, where the powerful feed upon the powerless.” He asked, in a line singled out for praise by former U.S. president Barack Obama: “How can it be that it is not a news item when an elderly homeless person dies of exposure, but it is news when the stock market loses two points?”

Francis criticized the market economy again in 2015, calling for a major reduction in the use of fossil fuels to reduce climate change, in his encyclical Laudato Si'. That year, in Bolivia, he exhorted a meeting of grassroots activists to struggle for their “sacred rights” to land, lodging, and labor—tierra, techo y trabajo—and also accepted a gift from the country’s left-wing populist president Evo Morales: a crucifix incorporating a hammer and sickle. He said he took no offense at the present and brought it back with him to the Vatican. The contrast was stark with Pope John Paul II, whose support for democracy against communism in his native Poland played a major role in the process that led to the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Soviet Union.

Francis could be highly polemical, berating theological conservatives as “rigorists” and fundamentalists. He was particularly severe with the small minority of Catholics who attend the traditional Latin Mass, the celebration of which he tightly restricted in 2021. He believed the rite had become a rallying point for Catholics who reject the modernizing reforms of the Second Vatican Council, which took place in the 1960s, and enabled, among other things, more active participation of laypeople in worship.

In an autobiography published earlier this year, Francis criticized Latin-Mass-goers, who extol the aesthetic and devotional qualities of that liturgy, as ideologues of “backwardism,” and wrote that the fancy vestments and lace of traditionalist priests “sometimes conceal mental imbalance.” Such invective likely reflected a naturally combative temperament, but there was also a strategic element: like the former Peronist he was (as a youngster he once sprayed an uncle with seltzer water for speaking against Evita), he used elites, including his own bishops, as foils to bond with the people. Though he was himself the supreme head of a hierarchy that heavily emphasizes obedience, and he did not hesitate to use his power whenever he deemed appropriate, he cast himself as the champion of laypeople and repeatedly inveighed against the vice of “clericalism,” or excessive deference to the priesthood.

There’s a striking symmetry in the timing of Francis’s death: the most influential and inspiring figure of the global left departs just as President Donald Trump’s return to power fuels a resurgent wave of right-wing populism worldwide. Underscoring that symmetry is the fact that his final public meeting was with J.D. Vance. He met the U.S.’s vice president, a Catholic convert, on Easter Sunday.

The week before he was hospitalized earlier this year, Francis sent an open letter to the U.S. bishops denouncing Trump’s deportation policy.

“The act of deporting people who in many cases have left their own land for reasons of extreme poverty, insecurity, exploitation, persecution, or serious deterioration of the environment, damages the dignity of many men and women, and of entire families, and places them in a state of particular vulnerability and defenselessness,” he wrote.

It’s a sign of the times that Trump didn’t respond to the pope’s criticism—unlike in 2016, when Francis suggested Trump’s anti-immigrant stance meant he was “not Christian,” and Trump shot back that it was “disgraceful” of the pope to question his faith. The incident was a rare public show of Francis’s formidable temper, and a rare political blunder by the pope, which helped raise the international stature of then-candidate Trump.

Vance did acknowledge the latest criticism, which included an extraordinary papal rebuttal of Vance’s argument that Catholic theology warrants giving priority to caring for one’s compatriots over caring for foreigners.

Francis got along better with Trump’s successor-predecessor Joe Biden. After certain U.S. bishops sought to deny the Catholic president Communion because of his support for abortion rights, the Vatican opposed them. Biden said the pope privately told him he was a “good Catholic.”

Yet Francis had a wary relationship with the U.S. in general, including with the Catholic hierarchy there—one of the most influential conservative blocs in the church’s leadership. He once said, about criticisms from conservative Catholics in the U.S., that he was “honored that the Americans attack me.”

That wariness extended to the U.S.-dominated world order, which helps explain his stance—baffling to many—on the war in Ukraine. Even before Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022, Francis angered Ukrainians, including members of his own hierarchy, by describing the struggle with Russian-backed separatists as a “fratricidal” conflict rather than a case of Russian aggression. Over the last three years, while often bemoaning the plight of “martyred Ukraine,” he avoided blaming Russian president Vladimir Putin for the war and repeatedly suggested that the invasion had been provoked by NATO expansion in Eastern Europe.

He also dismayed many of his followers in China, especially members of the so-called underground church that resists state control, with his overtures to Beijing. Francis’s policy of engagement with the rising superpower reflected his multipolar geopolitical vision, and his efforts culminated in an agreement to share power with the Communist government over the appointment of Catholic bishops. The pope was conspicuously silent on China’s human rights abuses. He referred to the Uyghurs as “persecuted” for the first time in 2020, and his critics contrasted this relative silence with his outspokenness on Western policies.

Outreach to Islam was a signature theme of Francis’s pontificate. He visited 13 Muslim-majority countries as pope and in 2019 issued a joint statement with a prominent Muslim cleric, Grand Imam of Al-Azhar Ahmed el-Tayeb, in support of “human fraternity.” It included a renunciation of violence in the name of religion. He also enjoyed good relations with Jewish leaders, but angered many in Israel when he likened the Israel Defense Forces’ operation in Gaza to terrorism, and suggested that Israel should be investigated for genocide.

And so Francis was in many ways a highly polarizing and divisive leader. He was known for his conciliatory approach to LGBT issues, which won him much applause in the West. He famously signaled a new tolerance by asking, of gay priests, “Who am I to judge?” He also met with trans people on several occasions. But this liberalism put him at odds with socially conservative church leaders in Catholicism’s fastest-growing region, Africa. Bishops there openly protested Francis’s decision in December 2023 permitting priests to bless same-sex couples—and in an extraordinary reversal the next month, the pope agreed to exempt Africa from the practice.

He was also challenged by the Catholic Church’s long-running scandal over clerical sex abuse, a problem he addressed reluctantly at times. His prolonged support of a Chilean bishop accused of covering up abuse prompted fierce criticism by victims’ groups in 2018 and he ultimately took a harder line. But he was less severe than his predecessor about removing priests found guilty of abuse from ministry, and critics said that measures he instituted to make bishops more accountable were applied inconsistently and without transparency.

So, although the death of a pope is always a momentous and solemn event for his followers, some Catholics are doubtless mourning less deeply than others today. Yet at his most iconic, Francis could be a unifying, solitary presence. On March 27, 2020, at the nadir of the pandemic, he stood in an empty, dark, and rain-swept St. Peter’s Square and invoked Christ crucified to offer hope to a shaken world. “Yet our faith is weak and we are fearful,” he said. “But you, Lord, will not leave us at the mercy of the storm. Tell us again: ‘Do not be afraid.’ ”

Francis spent his last weeks flouting doctors’ orders by venturing outside of his residence to mingle with the faithful, even taking a last ride in the popemobile through St. Peter’s Square on Easter Sunday. His insistence on remaining active till the end, and his apparent determination to observe Christianity’s greatest feast one last time, are reminders that a great part of his charisma lay in his strength of will.

Francis X. Rocca has covered the Vatican since 2007, including for The Wall Street Journal, where he also reported on global religion. He currently writes for The National Catholic Register.

For a look back at the life of Seraphim Rose, the “unofficial patron saint of lost Westerners,” read Paul Kingsnorth’s piece, “The Patron Saint of Lost Americans.”