The Free Press

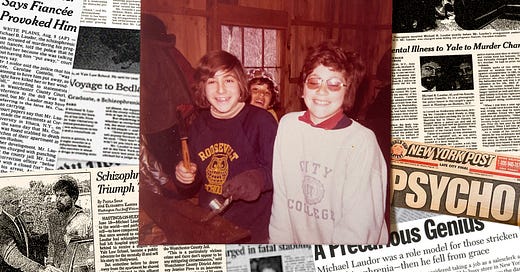

Michael Laudor was an exceptional boy. Academically, he excelled. Things that are hard for most young students, like reading multiple books at once and comprehending large volumes of material, came easily for him. His charm was infectious, and he seemed to immediately attract the attention of any room he entered. Through high school and college, one thing was clear: everyone was drawn to Michael.

Michael’s diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia in his twenties in some ways only added to his allure. On the day he was accepted to Yale Law School, he also believed that monkeys were eating his brain.

The New York Times wrote a glowing profile about his resilience. A major book contract for Michael’s memoir followed. Director Ron Howard bought his life rights and Brad Pitt was attached to star in a movie about Michael’s life.

But then, Michael Laudor did something unimaginable: he killed his pregnant fiancée.

The tragedy of Michael’s story is captured in Jonathan Rosen’s new book, The Best Minds: A Story of Friendship, Madness, and the Tragedy of Good Intentions.

It’s a breathtaking account of friendship and the harrowing and insidious nature of mental illness as it takes over someone’s life. Most of all, it investigates the invisible forces—cultural, political, and ideological—that shaped Michael’s terrible fortune, and America’s ongoing failure to get people like Michael the help that they so desperately need.

When I finished the book, I told Nellie that it was the best book I’d read this year. She rolled her eyes—I am infamous for overhyping things. But then she inhaled it in two days and declared it “maybe the best book by any living writer.” The reviewers seem to agree.

All of which is to say: you should read it. Especially if you care to understand how it came to be that so many believe that letting people die on our streets is a kind of freedom.

Start by listening to my conversation with Jonathan this week on Honestly, and find an edited, shortened transcript of our conversation below.

On meeting Michael:

BW: I want to begin where your remarkable book starts off, which is with your childhood best friend, Michael Laudor. Tell me about him and that moment you two met in New Rochelle in 1973.

JR: Michael and I were ten years old when we met. Our neighborhood street was very short. There were maybe seven or eight houses on it, and I met him right away because he walked over to say hello to me. We just started talking that day and kept on talking for years afterwards. It’s hard to describe exactly because part of the pleasure of being ten is that you’re actually not really thinking all that much. I was happy there was somebody on my street who came over to say hello. Somebody I could call for every morning, which I did on the way to school. Someone who played basketball with me. Someone who got my jokes, and I got his. He was very, very different from me, but we also had a lot of things in common.

BW: What’s striking about your descriptions of him in the book, especially knowing what’s become of him, is that even though you are best friends it seems like you feel as if you’re constantly living in his shadow. Like he’s always put him one step ahead of you. But then you both get into Yale. And you say that the summer before college, Michael told you that he didn’t think he’d see much of you at school. For what reason? He says it’s because “you’re too slow,” which I thought was kind of amazingly cruel. But you write this: “We carried the world of each other’s childhood in our pockets like a kryptonite pebble, a fragment of the home planet.” And I think many people, when they get to college, change in a way that feels sort of incompatible with their childhood. But there’s something especially sad to me about you and Michael side by side at Yale, like ships passing in the night. At one point you say it was like you were living parallel lives on divergent tracks. How do you understand this period in college between the two of you and how your friendship shifted?

JR: It’s a terrific question—and I’m not sure I know the answer. I went back after many years to think about this moment and wonder whether perhaps he wasn’t already becoming ill, perhaps showing signs of the illness that he later developed. I wonder if some of the very things I most admired about him, even if it was this kind of obnoxious way of declaring himself and his own abilities, if that wasn’t an exaggerated quality in him already then. I’m not entirely sure why I was too slow for him, but I do know that I probably thought of myself as the tortoise to his hare. And later, once he was ill, the race was still on. I actually probably relished the competitiveness without my knowing it, because it’s wonderful to have somebody you measure yourself against. I kept hoping I’d catch up long after I realized he, years later, had run off in a different direction entirely.

On genius and mental illness:

BW: On the day Michael was accepted to Yale—arguably the best law school in the world—he also believed that monkeys were eating his brain. Having spent so long with this story and this project, where do you land on the question of how genius and mental illness are fitted together?

JR: It’s a very good question. And I don’t know the answer. Partly because there’s a kind of cult of genius that was not so different from the cult of madness, as if it was a form of prophecy that rescued you from ordinary existence. It’s hard to know what genius even means, to be perfectly honest. Michael was amazingly smart. He had a photographic memory. He was always spoken of as being brilliant. But what does it mean if you’re seen as brilliant and yet you cannot do the work that’s expected of you? It’s almost as if it becomes a category that simply elevates you. It was like being an artist when Michael and I were young. I didn’t want to be a writer so I could come to terms with life in all of its complexity. I wanted to vault above and beyond it. It was a very unhealthy impulse, and I grew up in a world of writers. I grew up probably believing what I think Mallarmé, the poet, says, which is that the world exists to be put into a book. But I don’t believe that anymore. One of the reasons this book took so long to write is that I wasn’t just telling stories; I had to untell stories also. The impulse to make stories, this idea that somehow literature heals you or makes you whole, and telling your story means you’ve triumphed. . . there’s a way in which it doesn’t honor life. It does the opposite.

Everyone thought they were helping Michael by making his story come out a certain way so they would supply missing pieces of it, you know, like the frog DNA that they use in Jurassic Park. It’s very close, but it’s different. I think somehow this dream of genius is like that. Michael and I shared this idea that our brains were our rocket ships: we were just going to outsoar our ordinary existence. There’s this amazing line in the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley’s elegy for John Keats, who died very young, by the time he was 26. It says:

He has outsoar’d the shadow of our night;

Envy and calumny and hate and pain,

And that unrest which men miscall delight,

Can touch him not and torture not again;

I memorized it in high school, and I was, you know, sort of drunk on the music of it, until you realize what he’s saying is that he’s safe now. Why? He’s dead. So many of the theories that were imposed on life and imposed on literature, when I was in school, and imposed on medicine were not only untrue—they were antithetical to life. My father was right when he would say to me, quoting the Bible, “choose life.”

On dreams merging with reality:

BW: One of the things that you capture so powerfully in the book is the blurring of lines, the kind of collapsing of categories that happens during the sixties and seventies, where, as your Berkeley therapist put it, there’s no difference between real and imaginary, no difference between past or future. There’s one paragraph in the book that I thought so beautifully captured it, and I’m wondering if you’d read it for me.

JR: “Part of the playful pleasure of postmodern theory was pretending that a flaw in a poem was evidence of a crack in society, and that verbal constructs held true for three-dimensional life like a pin stuck in a voodoo doll that made a real person scream. What would happen if such fanciful borrowings from the realm of magic and mental illness began seeping into law, public policy, or political culture? Turning everything into a text that meant only what the interpreter believed it meant.”

BW: The reason I so loved that passage is because you write in the book about dream worlds. Here in this passage you talk about it as fanciful borrowings from the realm of magic; a world where sort of the unreal is being mistaken for the real. How did that culture factor into Michael’s development and story?

JR: I think it had a huge impact. It helped shape the world that was there when he became ill. A world that was so ill-equipped to care for someone like him. If you believe that all mental illness is a social construct, even severe mental illness, and that the only reason why asylums were built in the eighteenth century, as Foucault says, is as a place to put your enemies who you’ve othered by calling mad simply because they swim against the rational stream, then there really isn’t any illness. There’s only power. And the people who have power can call the people they hate ill. Now, there’s plenty of abuse of power. But if illness is real, then that formula deprives people of any form of care, and the only response to a hospital, a mental hospital, or a psychiatric hospital, is to treat it like the Bastille and tear it down. In fact, one of the most devastating passages in Madness and Civilization is about Philippe Pinel, who was the eighteenth-century reformist psychiatrist. He was really the father of humane psychiatry and he’s often depicted in paintings striking the chains from his patients because they were chained even inside the hospitals. And for Foucault, he is the villain. It takes a minute to realize that the reason he’s the villain is precisely because he improved the lot of people in those hospitals. The reforming impulse, the liberal impulse, is dangerous because the only response is the absolute destruction of that system and that world. The system of state hospitals that might have been reformed were instead effectively torn down and they were not replaced by anything equipped to care for the people who had once been in those hospitals.

Things like that—formulations like that—took place all the time. It’s Harold Bloom that says that “schizophrenia is bad poetry.” His whole theory was that you intentionally misread your predecessors so that you can insert yourself and make yourself primary by ignoring or misunderstanding what it is that makes them great. But that’s only possible if you do know that they are great. And if you really are in contention with something powerful, poetry has to mean something in order for you to contend with it. The reason why he said schizophrenia is bad poetry is because the misreading that it involves is not an intentional or constructive or creative misreading. It’s simply misperception. It was only much later that I learned that he had someone in his family who suffered from severe mental illness, and so for him, that was not an abstraction. These elaborate theories that erased meaning paled in front of his own experience of the world and of true illness.

On visiting Michael in the hospital after his first psychotic break:

BW: You describe, before you go visit him in the hospital for the first time, that you were worried and wondering if you might catch schizophrenia, like it’s a contagious disease. Even though of course you knew that was impossible. If you can, drop us back into that time, to your own mental state. What was it like seeing someone who you had so admired, maybe even envied, in that kind of condition?

JR: Well, it was shocking, and I didn’t want to go. I was terrified of going, and it’s partly because I think his mind was always a kind of touchstone of high functioning. Whether or not we were close friends at that point, I measured myself against him. So what did it mean that something had gone wrong with his mind? I was the one who forgot everything I had crammed into my head on the day of my bar mitzvah. I was the one who already had, as I called it, senior moments, and who had panic attacks. When I was preparing to visit him, he gave me all these instructions while still sounding surprisingly rational. He asked me to conceal a tape recorder at the bottom of my backpack, to buy a copy of the Literary Guide to the Bible by Frank Kermode and Robert Alter, and wrap it up and make sure the guards didn’t see it. I was dutifully getting ready to do all of these things until my then-girlfriend, now wife, said to me, touchingly, because she was clearly amused and felt bad for me, “I don’t think you actually do have to smuggle that dry work of scholarship into the hospital. I think they’ll let you just carry it in.” And that’s when I realized what had led me to sort of immediately participate. It was my habit of deferring to his authority. There is something enormously rational about his mind, even though it was based on an irrational premise and that was that sense of almost contagion. I didn’t want it to happen to me. I had no idea what it meant to be mentally ill or mentally well, for that matter.

BW: So Michael spends eight months in that hospital, but then he seems to turn things around in his life in a way that’s almost cinematic. Tell us about Michael going from being paranoid that his parents were stolen and replaced by fake-parent Nazis, to his fears that he was about to get lobotomized without anesthesia, to then somehow turning around and getting into Yale Law School. How does that happen? And was he open with people there about his diagnosis?

JR: Michael had applied to Yale, and all the top seven law schools, before he had his psychotic break. When I went to visit him, he told me he’d been accepted by all of them and that he had turned them all down except for Yale, which he had told his brother to defer. As he later put it, he did so while yelling, “The monkeys are eating my brains.” But before becoming ill, he cast out a little lifeline for himself, simply because his life was unraveling. He had deferred twice, he was not asked to reapply, and he was allowed to come. He was open with his professors. One of his professors felt he was almost promiscuous with the knowledge. He didn’t seem to understand that for many people it was an unusual thing to hear, and that it might affect how they saw him. He was very lucky in that he was surrounded by these extraordinary men of a certain generation who were very moved by him. They were very brilliant themselves and they saw him as brilliant, even though they understood that he could not do the work. He didn’t tell his fellow students at first about his diagnosis, although amazingly, people understood that there was something that had happened to him. He found people who really helped care for him. They read to him, they typed his papers, they got him meals. It was a revelation for me many years later, when I talked to those professors and learned that he really wasn’t able to do the work. They were confronting their own decision to accommodate him as they did because in Michael’s mind, he was there in recognition of his genius.

On the New York Times article that changed everything:

BW: What was the reaction to that article?

JR: It changed Michael’s life in remarkable ways—almost overnight—because the story was so powerful. In a sense, it conformed to everything we’d always imagined about writing, and Michael’s story was enormously compelling. I only really discovered afterwards just how many people saw him as a hero. There were very few people who spoke of themselves publicly as having schizophrenia. He spoke of himself as wanting to be a role model. He said, “I can be a role model.” I remember a woman, Laurie Flynn, who at the time was head of NAMI, the National Alliance on Mental Illness. Her daughter had been hospitalized for schizophrenia and they were both filled with admiration because Michael was declaring himself ill. . . . But it was such a compelling story.

BW: And it was noticed by people in Hollywood, right?

JR: Of course. He wasn’t just a role model flooded with letters. He got offers from publishers, he got offers from Hollywood. He called to tell me that there was a bidding war for his story, which was going to be called The Laws of Madness and that Ron Howard, who had just directed Apollo 13, wanted to make the movie. So it really did seem as if, by telling his story, he had been able to conquer, as someone says in his article, his illness, and all the obstacles that went with it. And now, suddenly, he was back where we had always imagined he would be.

On Michael’s descent:

BW: Let’s talk about the calamity.

JR: Well, Carrie stayed home from work, even though the next day she and her colleagues were all flying off to Chicago for a conference. She worked at the Edison Project, which was an educational project. She was assistant technology director, and it was a huge conference. It was unusual for her not to appear, but she didn’t. Carrie called in a family emergency and that day was full of frantic phone calls with Michael’s family, with mental health workers, with people trying to arrange some sort of crisis intervention. At one point, Michael’s mother became so alarmed by the things Michael had said that she called back. Michael answered the phone and his mother said, “Give the phone to Carrie.” And Michael said, “I can’t, because I’ve killed her.” Michael’s mother, Ruth, then called the police and asked them to check on Michael and his fiancée. Michael lived about 50 feet away from the police station in Hastings on Hudson, so two officers went over, and the door was locked. They got a key, they opened the door, and they found Carrie. She had been stabbed many times, and Michael was gone. He had fled in Carrie’s car, first to Binghamton, and then he took a bus to Cornell. But before he had gotten there, he had flagged a police car down and he was taken into custody.

BW: When Michael stabbed Carrie to death, did he know that she was pregnant with his child?

JR: He did. But to say, “Did he know?” is to say, to suggest, that he knew who she was. And that remains the great question of responsibility. He was found ultimately not responsible by reason of insanity, because he genuinely thought, as one psychiatrist said, that Carrie was a nonhuman impostor. So what he thought her child might be is also a question. But it was a shocking piece of news that Carrie was pregnant. I certainly didn’t know. Most people didn’t know.

BW: So you have this 1995 New York Times profile hailing Michael as a genius who overcame his invisible wheelchair, or his invisible handicap. And then the day after this murder, what is the headline in the New York Post?

JR: One word: psycho. So big you couldn’t even have added an exclamation point or the words would have fallen off the page.

On who’s to blame:

BW: I think you capture in a very powerful way in this book the sort of failure of the institutions—obviously the failure of mental health institutions in this country, the failure of hospitals—but also the failure of institutions like Yale. Michael described Yale Law School as “America’s most supportive mental health care facility.” And, as you write in the book, his fellow students, his professors, they did so much to get him through law school. They wanted him to succeed. They thought they could save Michael. There was talk at one point of Michael being capable of clerking for a Supreme Court justice. The dean of Yale Law School, as you mentioned, said that Michael was in an invisible wheelchair and that he would be the ramp. But did they inadvertently, even with the best intentions, participate in the delusion? Did they participate in the lie?

JR: One of Michael’s mentors said to me, “You know, if I wasn’t so busy thinking what an amazing place Yale Law School was for taking Michael, I might have thought more about how he was feeling.” And this was someone who had asked Michael, “Do you still hallucinate?” And Michael had said, “Oh, yes! I’m looking at angels right now waving fronds of fire.”

The professor said there was something so wrought about the image that he had to actually stop and ask himself if he was being bullshitted. He decided he wasn’t and they moved on. But the point is, it was actually the opposite. The stylized nature that made it seem almost literary was misleading. The reality was that he was still hallucinating and he couldn’t do the work. One of Michael’s professors said to me, “Don’t blame Hollywood,” because I had talked about how strange it must have been that Michael, who had delusions of grandeur, among other delusions, was suddenly going to see a handsome movie star playing him. But this professor said to me, “Don’t blame Hollywood. If Hollywood is to blame, we all are.” And of course, Hollywood’s job is making stories with happy endings. It’s not the job of the law school. And as he then said, “Yale Law School gave that story to The New York Times. The New York Times gave that story to Hollywood.” What Yale felt about Michael was that he was brilliant, and what was amazing about being brilliant was that it didn’t mean doing the work. It meant almost as if he somehow qualified for their good will. . . and that’s a very complicated thing for me to contemplate because I’m a product of that world.

To support more of our work, consider becoming a Free Press subscriber today:

Wow, thank You!

That was really interesting. It sort of makes me more confused about some things; particularly that I’m NOT manic depressive: How it missed me I have no idea, but I’m grateful. I have, however, experienced those “brain burst” moments, as I call them.

Maybe I’m just asking the wrong question.

I’ve gone through hell because of being smart. You’re a resource, not a person. I’d trade it in a heartbeat. I hate the thought of someone else going through that.

But that doesn’t mean it necessarily ought to be a protected class. Nevertheless, it does need some sort of protection - particularly in the workplace.

How I know? I watch TV news about the latest mass shootings. There obviously is a big problem in the US with guns in the hands of people who shouldn't have guns. Don't You agree?