The Free Press

DEARBORN, MICHIGAN—Abed Hammoud grew up in south Lebanon fearing the sound of Israeli war planes. The echoes of their engines were so commonplace that he told me he learned to differentiate between different kinds of fighter jets—and where they dropped their bombs—based on the noise they made as they whizzed overhead.

As we sat on a pair of sofas in the back corner of a coffee shop in downtown Dearborn, Michigan, sipping peppermint and chamomile tea, Hammoud, 58, tells me that whenever he hears thunder at night, he is transported back to that village in Lebanon.

“It’s going to be our turn,” he recalled his teenage self thinking as he huddled with his family inside his grandfather’s home. “I start praying. That’s all you can do. I never forget that—that feeling of helplessness.”

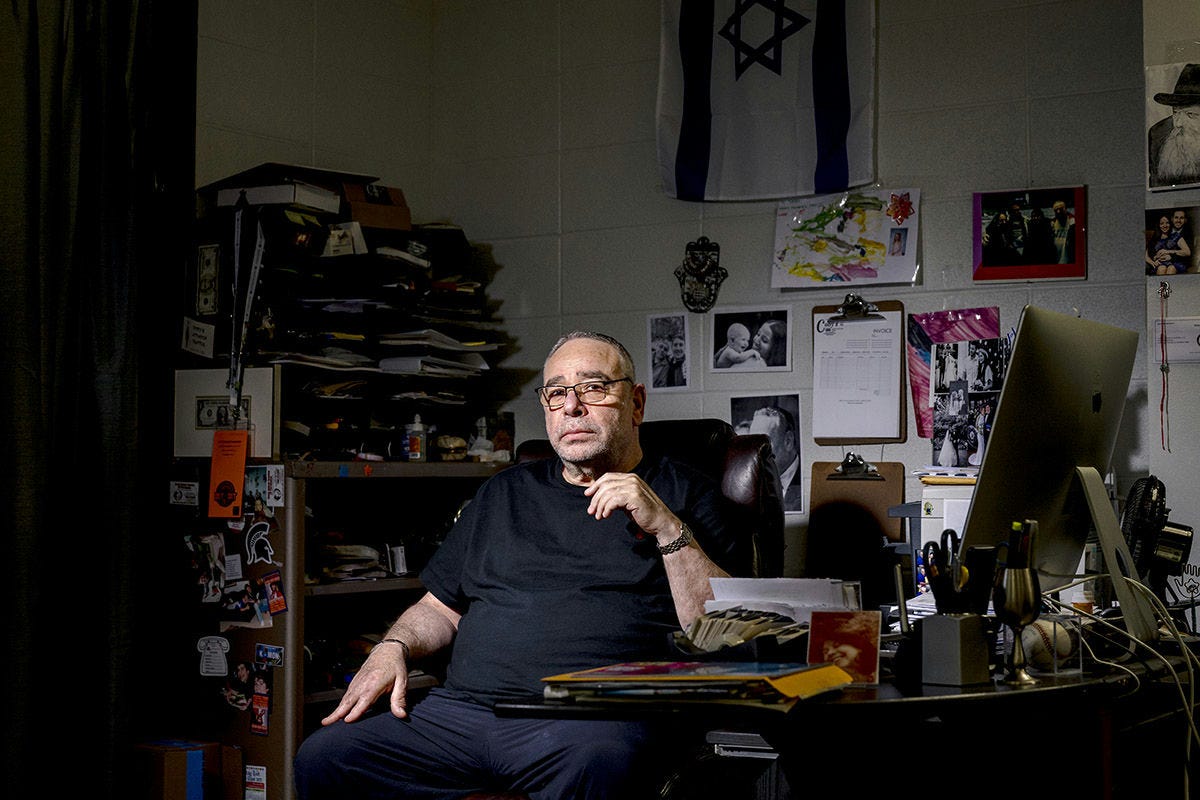

In nearby West Bloomfield, Coby Goutkovich, 64, tells me about his childhood in a small village in northern Israel—just on the other side of the border, not 40 miles from where Hammoud grew up.

He said he would never forget one night during the Six-Day War in 1967, lying in a ditch that he and his grandfather had dug in the backyard as a Russian-made Syrian bomber passed low overhead until an Israeli missile shot it out of the sky. “These things,” he told me, tapping his head with his right index finger, “are ingrained in the brain.”

Goutkovich moved to Michigan in 1989, built a career in construction and real estate, and raised a family of five kids with his wife of 22 years, who passed away last year. Hammoud, who is married with two sons, moved to the state in 1990, where he attended law school, then worked his way up to serving as a federal prosecutor for the Department of Justice and briefly worked at the U.S. embassy in Egypt.

But despite their geographic proximity now and as children, the two men inhabit wildly different political realities—and belong to two distinct communities in the Detroit metro area.

Goutkovich works in West Bloomfield, with a population of 65,000, at least 30 percent of whom are Jewish, and lives in nearby Farmington Hills, which has a similar demographic profile. Dearborn, where Hammoud lives, is a city of 100,000, over 50 percent of whom are Arab, largely of Lebanese, Yemeni, and Palestinian descent. West Bloomfield and Dearborn are less than 25 miles away from each other. But their residents’ perspectives on the war in the Middle East—and their views on who should win the presidential election in 40 days to bring it to an end—feel worlds apart.

The race in Michigan is unusually tight, with recent polling indicating that Donald Trump and Kamala Harris are in a statistical dead heat. In 2020, President Joe Biden won the state’s 16 electoral votes by fewer than 155,000 ballots—a margin of 2.8 percent of the total vote. In 2016, Trump won them with a lead of just 0.2 percent.

But this year, Michigan isn’t just a swing state, it’s a battleground—if not the literal kind that the people of northern Israel and southern Lebanon are currently experiencing, then certainly a proxy for the tension felt between two groups of people, separated by a few dozen miles and years of war and turmoil.

Consider the news of just the last week. After Israel launched a targeted attack in Lebanon against Hezbollah by blowing up their pagers, two different Dearborn mosques held services honoring the “martyrs” killed in the attack. At the University of Michigan, two people allegedly attacked a 19-year-old student after asking him if he was Jewish. When Dana Nessel, the state’s first Jewish attorney general, charged 11 University of Michigan anti-Israel demonstrators for refusing to leave their encampment in the spring, U.S. Rep. Rashida Tlaib, who represents Dearborn, questioned Nessel’s “possible biases”—a critique Nessel criticized as “antisemitic and wrong.” Governor Gretchen Whitmer initially refused to back Nessel, only to reverse course a day later, issuing a statement calling out Tlaib’s implication that religion impacted Nessel’s decision as “antisemitic.”

So while Jews and Muslims make up less than 4 percent of American voters (Jews represent 2.4 percent, Muslims represent 0.9 percent), who they are voting for—or who they refuse to vote for—says a lot about the state of the presidential race.

After a lifetime of voting for Democrats, Hammoud—who became a citizen in 1996—is planning to vote for Jill Stein. The Green Party candidate is the only person running for president, he said, who is “totally anti-war.”

Hammoud fears that his vote could lead to a second Trump term. (Third-party candidates in tight races are often accused of playing the role of spoiler. See: Ralph Nader in the 2000 presidential race.) But, he said, “I can’t in good conscience, today, if they stay the way they are, vote for Harris. What’s the difference between her and Biden?”

Like many Arab Americans in Dearborn—I spoke to more than half a dozen when I was in town—Hammoud believes that Israel’s campaign against Hamas in Gaza is not merely a war, but an “extermination.” He says Biden and Harris are aiding and abetting a “genocide”—a controversial accusation rejected by U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin.

Goutkovich, on the other hand, told me that since October 7, there is just one thing on his mind: security for Israel and America against Iran, their common enemy. That, he told me, is why he’ll be casting his vote for Trump.

As we sat in a small Judaica shop he runs in the West Bloomfield Jewish community center, Goutkovich told me that he narrowly escaped death several times while serving in the Israel Defense Forces. In 1983, while working with the American military, he said he survived the infamous terrorist attack on a U.S. Marine base in Beirut during which a suicide bomber drove a truck with over 12,000 pounds of explosives into the barracks. Over 240 Americans died in the attack.

Last week, Israel claimed it killed Ibrahim Aqil, who the U.S. government said was involved in the Marine-base attack, in a targeted bombing in Beirut. Goutkovich called his death “justice being done.”

“If [Trump] was in power four more years,” Goutkovich said, “today, there will be no Iran issue. He will demolish them, just with sanctions, not even a war, not even shooting one bullet.”

Goutkovich, who became an American citizen in 2012, said he doesn’t “see big issues between communities” in Michigan, even though he acknowledges how, in general, their understandings of the war—and the world—sharply contradict each other.

But despite what Goutkovich says, the tension is undeniable.

“I understand it, if there is a Palestinian and they feel bad, he’s going by what he listened to on Al Jazeera or whatever,” Goutkovich said. “That’s fine. So you want to express yourself, you are allowed to do it. But, don’t throw stones on me. Don’t intimidate me. Don’t try to make the point that you are right and I am wrong.”

“Don't bring the violence from the Middle East to America,” he added.

Hammoud, on the other hand, told me he reads Haaretz, the leftist Israeli paper, every day. He said he senses more sympathy toward Palestinians from the Israeli left than he feels from his Jewish neighbors in Michigan.

“It kills me that the Israeli left, or the Israeli people, intellectuals in Israel, are much more aware of what’s happening, much more in tune with it. And they’re saying, ‘Stop this war,’ ” Hammoud told me. “The Americans just give lip service.”

Historically, both the Jewish and Arab communities in Michigan lean left. There are just over 100,000 Jews in the state—over 60 percent of whom identify as Democrats. There are nearly 400,000 Arab Americans, 250,000 of whom are Muslim. More than half the residents of Dearborn have Middle Eastern or North African ancestry, and the city had been a stronghold for the left. In the 2020 presidential primary, 62 percent of Democrats in Dearborn voted for Bernie Sanders, compared to just 32.5 percent who supported Biden. Biden still went on to win over nearly 70 percent of heavily Arab American counties across Michigan in the general election.

But October 7 has shaken previous alliances, making once-ardent supporters on all sides feel disenfranchised by the political parties they once supported. And there’s no clear way either candidate can win over both communities.

Dearborn embodies this sentiment. The city’s mayor, Abdullah Hammoud (no relation to Abed Hammoud), refused to meet with Biden’s campaign staff ahead of the state’s presidential primary because of the administration’s support of Israel. Weeks later, 57 percent of Dearborn residents would vote “uncommitted” in February’s Democratic presidential primary—compared to just 40 percent who voted for Biden—a clear message that if Biden wanted to keep his supporters from 2020, he’d need to hear their demands.

Since Biden dropped out and Harris entered the race, it’s unclear if she’s had much luck regaining those voters.

In her public statements, Harris promotes a ceasefire at the same time she calls for the release of the Israeli hostages held by Hamas. But her insistence that Israel has a “right to defend itself” against enemies such as Hamas or Iran—as she spoke about at the Democratic convention last month—continues to alienate Dearborn’s “uncommitted” voters. It didn’t help when the Democratic National Committee declined to invite a Palestinian speaker, even one who would endorse Harris, to speak at last month’s convention.

Last week, the Uncommitted Movement released a statement discouraging their supporters from casting a “third-party vote in the presidential election, especially as third party votes in key swing states could help inadvertently deliver a Trump presidency given our country’s broken electoral college system.” The group stopped short, however, of endorsing Harris.

Recent polling from the Council on American-Islamic Relations shows Stein ahead with Muslim Michigan voters, with 40 percent of respondents backing her, followed by Trump with 18 percent and Harris at 12 percent.

The most prominent Muslim for Trump is the mayor of nearby Hamtramck, Yemeni immigrant Amer Ghalib, who recently endorsed the former president, saying that Trump wants “to end the chaos in the Middle East and elsewhere.” Hamtramck is America’s only city governed entirely by Muslims—and has been a fixture of the country’s culture wars, especially in schools and libraries.

Hamzah Nasser, who owns Haraz Coffee House on Michigan Avenue in downtown Dearborn, two blocks from the Arab American National Museum, is another.

Nasser, 37, knows what it’s like to live in a war zone. When he was 6, his family fled the civil war in Yemen and settled in Dearborn, where Nasser attended school, started his first business—a gas station—followed by his own trucking company, before he opened the first of his chain of coffee shops in 2019.

Since the war broke out, Nasser said his business—which imports its coffee beans from his home country of Yemen—has been severely impacted by shipping issues caused in part by Houthi rebels who have been attacking cargo ships in the Red Sea. In August, a shipment originally budgeted to cost $25,000 ended up being $52,000, he said.

Nasser thinks Trump will be able to put an end to his shipping woes more quickly than Harris. “He kept the peace with all these so-called dictators,” he told me. “I think Trump is going to stop the war.”

“Only thing in my mind is making money and building a better future as an American citizen,” Nasser texted me after our conversation. “Wars only cost money and lives.” (But Nasser is far from a typical MAGA voter. He doesn’t identify as a Republican, for starters. And what would be a sign of apostasy in the GOP, he believes Tlaib, the Palestinian American member of The Squad in Congress, is a “woman of principle,” and he plans to support her in November, too.)

Jackie Victor, a 59-year-old born in the suburb of Bloomfield Hills who now lives in Detroit, is a lifelong progressive and activist who has dedicated her life and career to fighting for social-justice causes like environmentalism and Black Lives Matter. In the past decade, Victor told me she started noticing a tension between her progressive community of friends and her connection to Israel, which she said has always been “embedded in me, in my cellular structure.” But, she said, “I was able to just ignore the contradictions, honestly. And now I see I was probably willfully ignoring it.”

Then October 7 happened.

“Almost immediately, I felt like I was politically homeless,” Victor said. She noticed some activists she’d previously marched alongside were suddenly declaring that “if you’re a Zionist, then you have no place in this movement.”

But watching Harris’s speech at the Democratic National Convention restored her faith in her own party. “I was reminded of who I still think is the majority of the Democratic Party,” she said.

Victor is planning to vote for Harris and is canvasing for her. New polling from the Democratic think tank Jewish Democratic Council of America shows that she’s not alone—68 percent of Jewish voters across the country said they planned to vote for Harris, compared to 25 percent who will support Trump.

But even though Harris has her vote, Victor told me, “I’m fucking anxious.”

“She’s saying, ‘I do support Israel,’ and that is not a politically safe thing for her to say,” Victor said. “But I do have this low-level anxiety about what comes next. What do the policies look like? How about if we go to war with Iran?”

That’s exactly the sense of apprehension Trump is trying to exploit. At the presidential debate on September 10, Trump said Harris “hates Israel” and warned that if she’s elected, “Israel will not exist within two years from now.” He’s also previously said that any Jewish voter who would vote for Harris over him “should have their head examined.”

Victor called Trump’s comments “disparaging.” “His loyalty towards anyone, especially, I believe, the Jewish community, is based on what benefits him in the moment,” she said.

Adam York, a 32-year-old Jewish voter from West Bloomfield who works in real estate, sees Trump more positively. “He’s not saying there is something wrong with Jews in general. He’s saying Jews who think Kamala supports Israel in a way or more than he does that they should look deeper. Of course, his verbiage is horrible, but he’s not saying Jews should get examined. He is saying, ‘Be informed who you’re voting for.’ ”

Elayna Jordan, 29, once considered herself “very blue”—a feminist activist who advocated for LGBTQ causes and abortion rights. She grew up in Farmington Hills, just south of West Bloomfield, and attended a Jewish day school in Bloomfield.

After attending college and living in Chicago for a few years, Jordan said she started moving toward the center on issues like taxes and the economy. She also said she witnessed a concerted effort from the left to paint the world as a struggle between the “oppressed” and “oppressors”—and Jews, she noticed, were always labeled as the latter.

Jordan is now back in the area where she grew up, living in Ferndale, just ten miles north of downtown Detroit, a suburb known for its Victorian-style houses. Since October 7, she told me that antisemitism—especially from her Arab neighbors, and a slew of activists who have joined their cause—has been pervasive.

“I can’t go anywhere without seeing ‘Free Palestine,’ or ‘We hate Zionists’ written on bathroom stalls and carved into tables at public spaces,” Jordan said. “You would never see that happen with other minorities, ever.”

Concerned about Hillary Clinton’s ethics, Jordan voted for Trump in 2016, she said. But in 2020, she didn’t vote because she didn’t trust either candidate—and her concerns about Trump were only heightened after January 6. But this year, after the eruption of antisemitism after October 7, she told me she plans to vote for Trump once again.

“There’s still people that are very fearful of Trump, and I can understand why, just based on his demeanor and the things that he says and his history,” Jordan said, “But, you know, I think that there’s a larger picture here. And I wish other people could see that.”

She also recognizes there’s not a perfect political home for her in today’s climate. The extremes of both parties, she said, have become “so anti-one another that they’re touching each other.”

“All this antisemitism and all that rhetoric has brushed up on each other. Now it’s like they’re joining hands,” Jordan said. Earlier this year, a group of white nationalists tried to hold a rally in Detroit to protest being kicked out of a conference held by a more mainstream conservative group—but the rallying cry quickly turned toward Jew-hatred. One of the attendees was former Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke, who declared he was there to “save us from Jewish supremacism because we’re being genocided just like the Palestinians, just [in] a different form.” Another, online commentator Nick Fuentes, declared that Israel is “committing a genocide against the Palestinians in Gaza” in order “to carve out a path for ‘greater Israel.’ ”

Jordan said she hears similar protest cries coming from the far left, and from just down the road, in Dearborn.

Just three days after Hamas’s terrorist attack on Israel, a crowd in Dearborn gathered in a theater and cheered as a local imam stated that a “fire in our hearts that will burn” Israel “until its demise.” Days later, another imam referred to the October 7 attack as a “miracle come true.” In April, a crowd of pro-Palestinian protesters rallied in Dearborn and chanted “Death to America” and “Death to Israel.”

Those chants were denounced by community leaders in Dearborn, including Imam Mohammad Mardini, the spiritual leader of the American Muslim Center, who told The Detroit News that “we do not accept, or share, the attitude that was expressed in those chants."

Mardini is a Lebanese immigrant who first came to the United States in 1980. At the Democratic National Convention in 2008, he presided over an interfaith ceremony in front of the conventions’ hundreds of delegates.

Speaking by phone, Mardini told me that he preaches to his congregation that “God created us equally” and that “we came the same, and we leave this life the same. The only difference is what we do in our life.”

But that’s not what’s most on his mind when he thinks about the election.

“My concern is our domestic policies concerning our kids and grandkids and every American. That they deserve to live, you know, free of worries, of all of this inflation and economic unrest,” Mardini told me. He said he’s still not sure who he will vote for, although he is leaning toward Harris after watching her debate with Trump.

Many of Mardini’s congregants, however, are more conflicted about what to do in November. Many, he said, plan to vote for Stein.

He said most people confess to him that they know Stein—who is polling at just 1 percent nationally—won’t win the election, or even Michigan. But he said they tell him they feel that, given the options of Harris or Trump, they have no other choice.

“They are looking for an alternative for what’s going on,” Mardini said. “They are trying to send them both a message.”

Francesca Block is a reporter for The Free Press. Read the piece she co-wrote with Joe Nocera, “Is Tim Walz Really Guilty of ‘Stolen Valor’?,” and follow her on Twitter (now X) @FrancescaABlock.

And to support more of our work, become a Free Press subscriber today:

As angry as reading this makes me against the antisemites of Michigan, it’s important and helpful to hear the other side. Not to see it from their point of view, F that! But it’s important to know what we’re up against. It pains me, but we could use more articles like this.

If you are voting for Jill Stein, you might as well throw your ballot into the trash. It's the eqvivalent of not voting.