The Free Press

Douglas Murray’s Things Worth Remembering column is taking a brief summer hiatus. The man deserves a break! He’ll be back in your inbox next Sunday, we promise.

But today we have something really important for you from Ben Kawaller.

This month—Pride month—he headed to the site of the most infamous anti-gay hate crime in American history. In October 1998, in the small town of Laramie, Wyoming, a 21-year-old college student named Matthew Shepard was brutally beaten to death because he was gay. Or that’s what we were told.

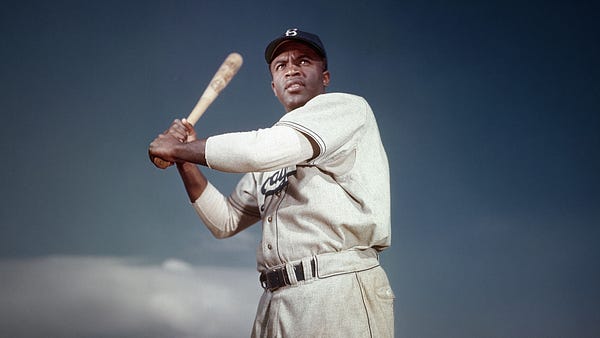

The murder was met with national outrage and mourning. And it became a rallying cry for a movement aiming to stamp out anti-gay hatred once and for all. As New York congressman Sean Patrick Maloney once put it: “Shepard is to gay rights what Emmett Till was to the civil rights movement.”

Ben—like me and so many others—grew up believing in the story of Matthew Shepard and what his murder meant about America. Or at least certain parts of the country.

But then, a few years ago, Ben heard another narrative. It caused him to wonder: Was the story we heard true? And what would it mean if Matthew Shepard wasn’t murdered for being gay, but rather for something more common—though equally as tragic? And why, when some investigative journalists discovered a more complicated truth, did so many people refuse to believe it?

So Ben Kawaller returned to the scene of the crime to talk to the people of Laramie and to ask them: What do they think? And how did this murder—and the story about the murder—shape their understanding of themselves and their hometown?

Today, the real Matthew Shepard story. And why the full, complicated truth still matters.

Make sure to scroll to the bottom to watch Ben’s powerful report. —BW

Most people who’ve heard of the 1998 murder of Matthew Shepard remember the story. A gay 21-year-old college student in Laramie, Wyoming, approached two strangers at a bar. Offended by his advances and wanting to punish him for coming on to straight men, the two pretended they were gay only to lure Shepard into their truck. They then drove him to a prairie, tied him to a fence, bludgeoned him with a pistol, and left him there, barely conscious. He was found some eighteen hours later and taken to a hospital, where he died several days later.

I was fourteen at the time of Shepard’s murder and was maybe six months away from coming out of the closet myself. I had an inkling of what I was, though, and I experienced the news of Matthew’s murder with a hefty sense of relief that I was safely ensconced in a progressive neighborhood in Brooklyn, where I was being raised by the rare set of American parents who could have stood to instill more sexual shame in their children.

Mostly, though, the crime left me with a fear of my fellow citizens—more or less anyone outside the tristate area. Venture into the heartland, it seemed, and you could very well end up meeting a bloody death at the hands of a couple of rednecks out to teach a fag a lesson.

After all, that’s what happened in Laramie, according to the press. It’s also the version of the story immortalized by Moisés Kaufman and the Tectonic Theater Project, whose interviews with the people of Laramie served as raw material for their iconic play (and eventual HBO film) The Laramie Project. And it’s the story that continues to be told today by news outlets, LGBT advocacy groups, and school curricula.

Keep in mind that Shepard’s death came at a time when gay men and women were regularly reviled on the national stage. There had been major cultural gains in the late ’90s. Will & Grace had premiered only two weeks before Shepard’s murder, for example. But government and religious leaders were still very much in the business of denigrating homosexuals. A gruesome homophobic murder felt like just the kind of thing that might take place in a society where senators openly compared homosexuality to alcoholism and pastors blamed gay tolerance for terrorist attacks.

The murder led to a national outpouring of sorrow and rage. “In our shock and grief, one thing must remain clear: hate and prejudice are not American values,” said President Clinton. It also made activists out of Shepard’s parents, Judy and Dennis, who still run the Matthew Shepard Foundation, which aims to “amplify the story of Matthew Shepard to inspire individuals, organizations, and communities to embrace the dignity and equality of all people.” The organization, whose most recently available tax documents reveal an annual revenue of around $1.2 million, credits itself with helping to pass a 2009 federal hate-crimes bill and with providing anti–hate crimes training to law enforcement officers. They have also “created dialogue about hate and acceptance” and compiled “resources” to support LGBT-related causes.

Evidently, someone feels these efforts have paid off: earlier this year, President Biden awarded Judy Shepard the Presidential Medal of Freedom. (The Matthew Shepard Foundation declined to participate in this story when I reached out for an interview.)

A cynic might note that a great deal of money has been invested in the Matthew Shepard story. And, as it turns out, the truth of the Shepard murder is indeed more complicated—and less politically palatable—than a story about a gay boy beaten to death by a couple of homophobic thugs.

Nearly twenty years ago, in the fall of 2004, ABC News ran a 20/20 segment, co-produced by the journalist Stephen Jimenez, positing that the attack on Shepard was motivated not by hatred of homosexuals but by drugs and money. That argument was fleshed out in Jimenez’s 2013 The Book of Matt: The Real Story of the Murder of Matthew Shepard, which reveals that Matthew Shepard had been dealing meth and was killed by a rival dealer who wanted to rob Shepard to pay his debts. His murderer, Aaron McKinney, is currently serving a life sentence, as is McKinney’s accomplice, Russell Henderson. (As Jimenez explains, Henderson was pressured into accepting a plea deal, despite his not having laid any blows on Shepard, in part because the county had enough money only for one trial.)

The backlash to Jimenez’s book was fierce. Though it garnered generally positive reviews in the mainstream press, many gay critics and activists assailed Jimenez’s reporting—though not always from a place of insight. “Why I’m Not Reading the ‘Trutherism’ About Matt Shepard” was the title of an op-ed in The Advocate. The reason given? “It feels lurid and cruel.” Media Matters published a supposed “debunking” of the book that tried to argue that Jimenez’s use of anonymous sources, many of whom were detailing involvement in criminal activity, invalidated his reporting.

Perhaps as a result of these responses, Jimenez’s insights failed to permeate the national consciousness. Nor have they made much of a dent in the gay consciousness, if my informal survey of fellow sodomites is any indication. Somehow, it wasn’t until 2019 that I caught wind of Jimenez’s argument. I immediately bought his book and devoured it in disbelief: How in the hell could so many of us believe a story that, upon investigation, appears to be fundamentally untrue?

That is the question that guides this special edition of Ben Meets America for The Free Press. I traveled to Laramie because I wanted to know why the legend of Matthew Shepard had endured for so long. And did the people of Laramie secretly doubt it? Or were they still true believers more than a quarter of a century later?

I came to Laramie for PrideFest, a weeklong program of cultural events produced by and for its small but vocal queer community. I interviewed a number of attendees, but I also mingled with the general public to get a sense of how the Matthew Shepard murder had affected those who lived there at the time, and what story they believed.

What I found was a microcosm of American polarization. On the one hand you had straight people, who seemed to believe the Shepard murder was mostly about drugs. On the other hand, you had the attendees of Laramie PrideFest, who thought it was about hate.

And yet even this straight/queer division ignores some nuance. For example, when I struck up a conversation in a coffee shop with a gay woman my age who grew up in Laramie, she said she thought Matthew Shepard had been killed over drugs. I wanted very badly to interview her on camera, but she wouldn’t allow it.

“It feels wrong in my heart,” she told me.

“I get it,” I told her. People don’t like to draw attention to themselves when they’re marching against the tribe.

“Why do you care about this?” she asked me, in all earnestness.

I told her the mythology around Matthew Shepard had damaged my perception of rural America—and maybe the rest of the nation’s as well. I told her I thought Laramie had been screwed—by the media, by Moisés Kaufman, by every contributor to The Laramie Project. I probably said something self-aggrandizing about this project being an olive branch, a gesture of amends from a member of the gay community to another community we had dragged through the mud. I may have said something about meth, and how devastating it has been, for everyone, but especially for gay people, though we don’t talk about this blight on our community that has taken so many lives—certainly many, many more lives than homophobia ever claimed.

I said all of that and asked her again, in my kindest voice: “I’d really love to interview you.”

She said she’d think about it. That was the last I saw of her.

Please click below to see the video of my time in Laramie, the town that gave birth to a myth that, it seems, it will never shake.

Ben Kawaller is a writer for The Free Press, and the host of our interview series Ben Meets America—which you can watch in full here. To listen to Bari talk to Ben about his reporting for this special report, click the Honestly episode below:

Do you have a unique perspective on this story? If so, we want to hear about it. Please write to us at letters@thefp.com.

And to support our work, become a Free Press subscriber today:

Thank you for sharing. Never knew of the drug dealing or that Sheppard had a drug problem. Play stupid games win stupid prizes. I feel for the people of Laramie and all other small towns in America always painted in a bigoted light used by the media and political parties to spread hatred for each other and in our country. Still the best country I know!

This was a pretty heartbreaking read, and then listen - the podcast is well, well worth the time relative to the short summary that is the article. Perhaps most heartbreaking to me was listening to the people he interviewed at Pride, all to a person not just disinterested in the factual reality, but resentful of the very idea that the factual reality should be of any import whatsoever. I thought Ben’s defense of truth on its own merits was compelling in its specificity - I would not have come up with a defense nearly as compelling on the spot in an interview. But upon some reflection, I want, if perhaps into the void, to add a small defense of my own.

Trust is perhaps the hardest won, and most delicate thing in this world. A great deal more is untrue than is true. Almost nothing is entirely true. Probabilistic universe and all that. Trust should be hard earned in this context. It demands an immense leap of faith. Lies, on the other hand, are cheap and plentiful. It is much easier to build a cause on lies for this reason. They are simply easier to come by, and can be conjured whenever needed to buttress whatever you need to buttress. But to do so is to resign your cause to ephemerality, and to undermine the work of those who share it and wish to see it endure. Not only does a foundation of lies besmirch any claim you might stake to justice, it will never replicate the impact of convincing someone your cause is just because it derives from what is true. If it’s just one of many competing myths, what incentive is there to stray from the comfort of your pre-existing internal narrative? Your identity is likely built on that narrative. It is a costly thing to reconstruct. So yes, the reality of a cultural touchstone moment like this very much does matter. Because if it is the foundation of what changed someone’s mind and values, imagine the indignation and retrograde you will reap if and when they learn as much. Any grander truth you built on top of it is now in danger of falling into the quicksand along with it.