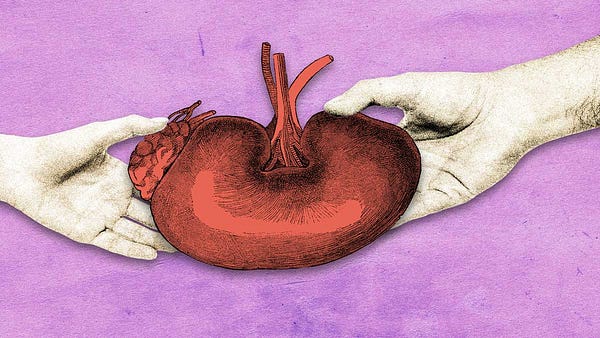

Last Tuesday, Mass General Brigham announced it will stop reporting to child welfare officials suspected incidents of abuse or neglect solely because a fetus or a newborn is exposed to drugs.

The Boston health network’s new policy also requires written consent for testing of any expectant woman or infant outside of emergency situations. It also limits testing to circumstances where results “will change the medical management of the pregnant person or infant.”

What to do about fetal exposure to drugs is a hard problem. Doctors want and need to help without frightening patients away; generally they should involve state child welfare authorities only as a last resort.

But grappling with this tension was not the motive behind the new policy. Instead, the changes were made in the name of social justice, or “health equity.”

Sarah Wakeman, MD, Mass General Brigham’s senior medical director for Substance Use Disorder, described the policy as “the latest step in our efforts to address long-standing inequities in substance use disorder care.”

A press release justifying the change noted that “black pregnant people are more likely to be drug tested and to be reported to child welfare systems than white pregnant people.”

But drug testing shouldn’t be equally applied across groups; it should be driven by the circumstances of each individual patient.

And if black babies are indeed exposed to drugs—and health professionals detect it—personnel can fast-track their mothers to treatment and vital social support.

Should a woman refuse help and her unborn baby or newborn’s health appears compromised, even if not emergently (as the policy stipulates it must be), it may be time to report.

The Mass General Brigham policy revision comes at a time when social justice is infecting medicine and public health. During Covid-19, national experts argued for giving priority to minority patients in distributing the new vaccine—a plan that would have likely resulted in more deaths overall. Brigham and Women’s Hospital (part of the Mass General Brigham system) is undertaking a pilot in which admissions of patients with heart failure to specialty cardiac units is based partly on race.

These clinical considerations flow from the politics of group identity, not from the best interests of individual patients—which is the north star of medical ethics.

Mass General Brigham has decided to conceal potentially valuable health information from medical professionals in the name of social justice. In doing so, it may end up disproportionately compromising the well-being of black women and babies. The success of this new policy should be judged by whether it improves health outcomes for all, not because doctors drug-tested fewer black patients.

Sally Satel is a practicing psychiatrist who treats drug addiction, a lecturer at the Yale University School of Medicine, and a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.

For more on “antiracism” in medicine, read Jeffrey Flier’s recent essay for The Free Press: “Medical schools should ‘combat racism.’ But not like this.”

Become a Free Press subscriber today:

I grew up during the ‘50’s in a limited family who had escaped Hitler, or had already been in the US and experienced the depression. At family gatherings everyone praised FDR and voiced support for Adlai Stevenson. Protesting against Vietnam in the ‘60’s and as much of a member of SDS as anyone could be, my political was always democrat or more extreme. Humphrey was a disappointment/sellout.

Those days have past. Now, day after day we read of egregious actions against people and democracy, and all those actions are those of democrats. We read of slanted media, all of whom are democrats.

My father’s (1903-1992) democrat party ceased to exist long ago. While republicans are also afflicted with a new SDS (spending derangement syndrome), I am more likely to support them having a hand in running our government.

Of one thing I am certain, today is democrats have no shame.

Not an OB nurse but aware of the high Black mortality rate during labor and postpartum. To me the change in policy must be evaluated as risk (to the mother and newborn) versus benefits. If the maternal mortality rate increases at Mass Gen Brigham post initiation of this policy, then the risks have outweighed the benefits.