The Free Press

While driving to his SpaceX internship in Texas in March 2023, 22-year-old Luke Farritor was listening to a podcast about a niche use of artificial intelligence: deciphering ancient scrolls. Then, he heard about a new competition—called the Vesuvius Challenge—being offered to the first person who could use AI to decode an ancient scroll from the ruins near Pompeii.

The prize? One million dollars. And anyone with a laptop could compete.

Farritor, then enrolled as a computer science major at the University of Nebraska, learned Latin as a kid and used to spend hours in history museums, but he never considered the classics an especially lucrative pursuit. That was until he heard about the Vesuvius Challenge.

“I got home that day and just got going and never stopped,” Farritor told me.

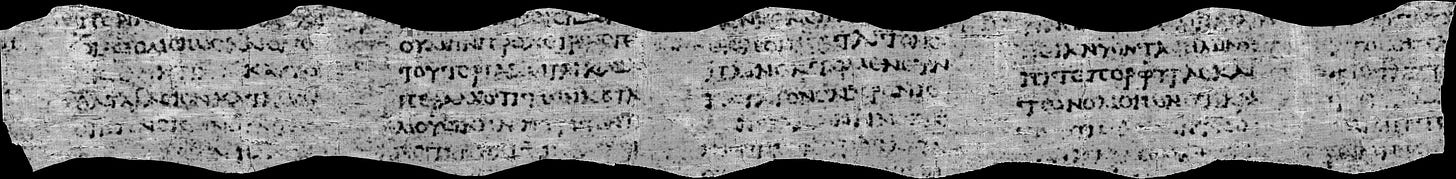

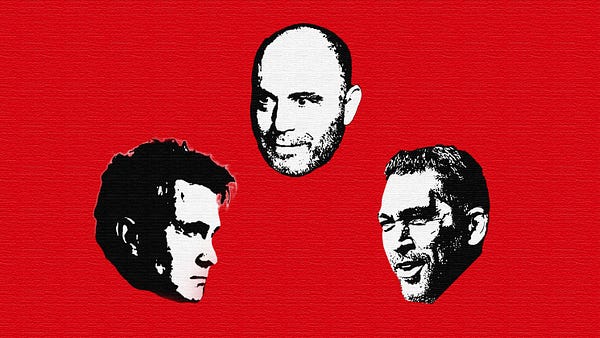

The competition, organized by Silicon Valley entrepreneurs Nat Friedman and Daniel Gross, and Dr. Brent Seales, a computer science professor at the University of Kentucky, launched on the Ides of March last year. Contestants had until the end of 2023 to decipher one of around 1,000 Herculaneum Papyri scrolls recovered from the library of the Villa dei Papyri, which was decimated by the same 79 CE eruption of Mount Vesuvius that froze the city of Pompeii in time. Discovered in the eighteenth century, the excavated scrolls have been sitting in museums and universities around Europe, unable to be touched “without them turning to ash,” Farritor said.

The materials from what was once one of the largest libraries in the ancient world, attached to a villa belonging to Julius Caesar’s father-in-law, have long had potential to reshape our knowledge of ancient history. Historian Garrett Ryan wrote that the recovered scrolls “will transform our knowledge of classical life and literature on a scale not seen since the Renaissance.” Before the Vesuvius Challenge, little was known about who wrote the scrolls or what they said.

Last week, Farritor was announced as one of the winners, receiving more than $250,000 in prize money, and was coolheaded about the news. When I asked him how he felt about the prize, he said he was “relieved.” The contest also landed Farritor a job: he has dropped out of college and now works for Friedman, “mostly doing investing stuff.”

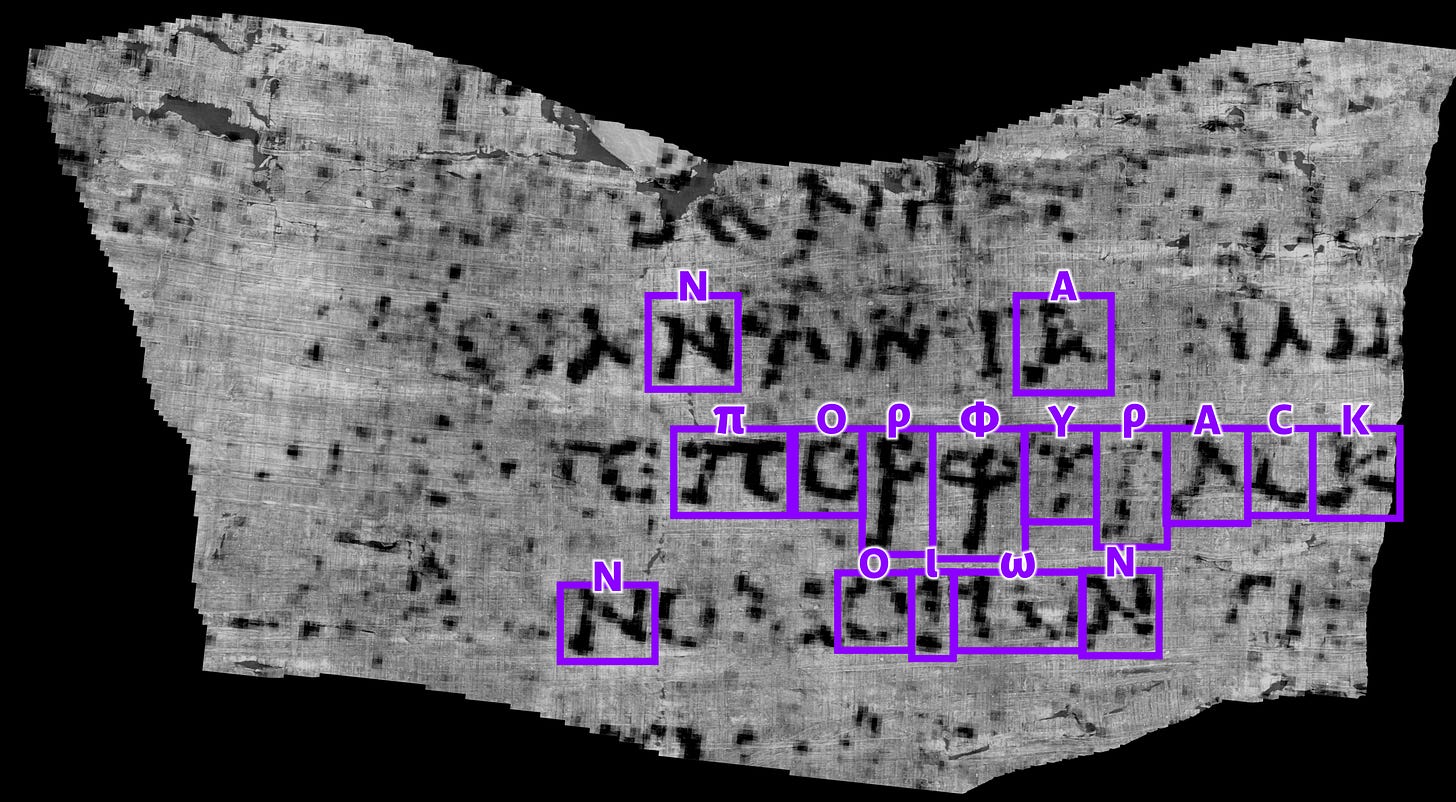

Farritor explained to me that his AI program took the image of the scroll and chopped it up into “tiny bits of 100 pixels by 100 pixels. And then the machine learning algorithm looks at each one and it asks itself, do I think there’s ink here? Or do I think there’s no ink here?” By compiling these tiles, the AI program can do what was impossible only a few years ago: read the scroll.

In October, seven months after he’d started his work, Farritor won the $40,000 First Letters Prize for finding ten characters in a small area of a scroll—the word “ΠΟΡΦΥΡΑϹ,” used in ancient times to indicate purple dye or purple cloths. In Roman times, purple was a symbol of high status and imperial authority because of its scarcity.

Weeks later, Youssef Nader, an Egyptian living in Berlin, independently found the same word. The two teamed up with Swiss student Julian Schilliger, whose work has enabled 3D mapping of the scrolls, and on February 5, the three students were announced as winners of the $700,000 top prize for deciphering five percent of the scroll.

The deciphered text was an Epicurean work of criticism, likely by the scholar Philodemus, who lived in the first century BCE. In it, Philodemus criticizes the Stoics, who, he writes, “have nothing to say about pleasure.” As the competition organizers note, this line “seems familiar to us, and we can’t escape the feeling that the first text we’ve uncovered is a 2000-year-old blog post about how to enjoy life.”

Farritor hopes that his team’s code can be used to read the remaining 95 percent of this scroll as well as the other manuscripts from the Herculaneum Papyri. On top of the scrolls discovered so far, experts believe many more remain unexcavated. “There are hundreds of these scrolls that we want to scan and read,” Farritor said. “And then there’s probably hundreds more that are still there.”

The Vesuvius Challenge will continue to incentivize further work into reading the scrolls—and redefining what we know about the ancient world—using checks from wealthy donors, including more than $2 million from the Musk Foundation. The next challenge is to read 90 percent of four scrolls.

Farritor predicts that reading these ancient scrolls “will completely upend our understanding of the ancient world. There’s just so much work that was lost.” At present, much of our understanding of ancient Rome comes from gluing together “guesses on other guesses.” To have access to an ancient library is “going to rewrite a lot of the assumptions we have,” he added.

For now, Farritor and his team have their work cut out for them: “All of our efforts are going to be just focused on reading the rest of this library.”

Read Julia Steinberg’s last article for The Free Press, a look at Silicon Valley’s e/acc evangelists, “Move Fast and Make Things.” And follow her on X @Juliaonatroika.

Become a Free Press subscriber today:

I hope someone is working on an update to this story - how life has changed for Mr. Farritor!

Very Cool. I hope Luke continues to be enthralled by wonders like these scrolls. And that his investing work leaves time for wonders. As someone else mentioned, not covered is the work of the PET scan or whatever they used to digitally "slice" the scrolls into thin layers to find and isolate the sentences.