The Free Press

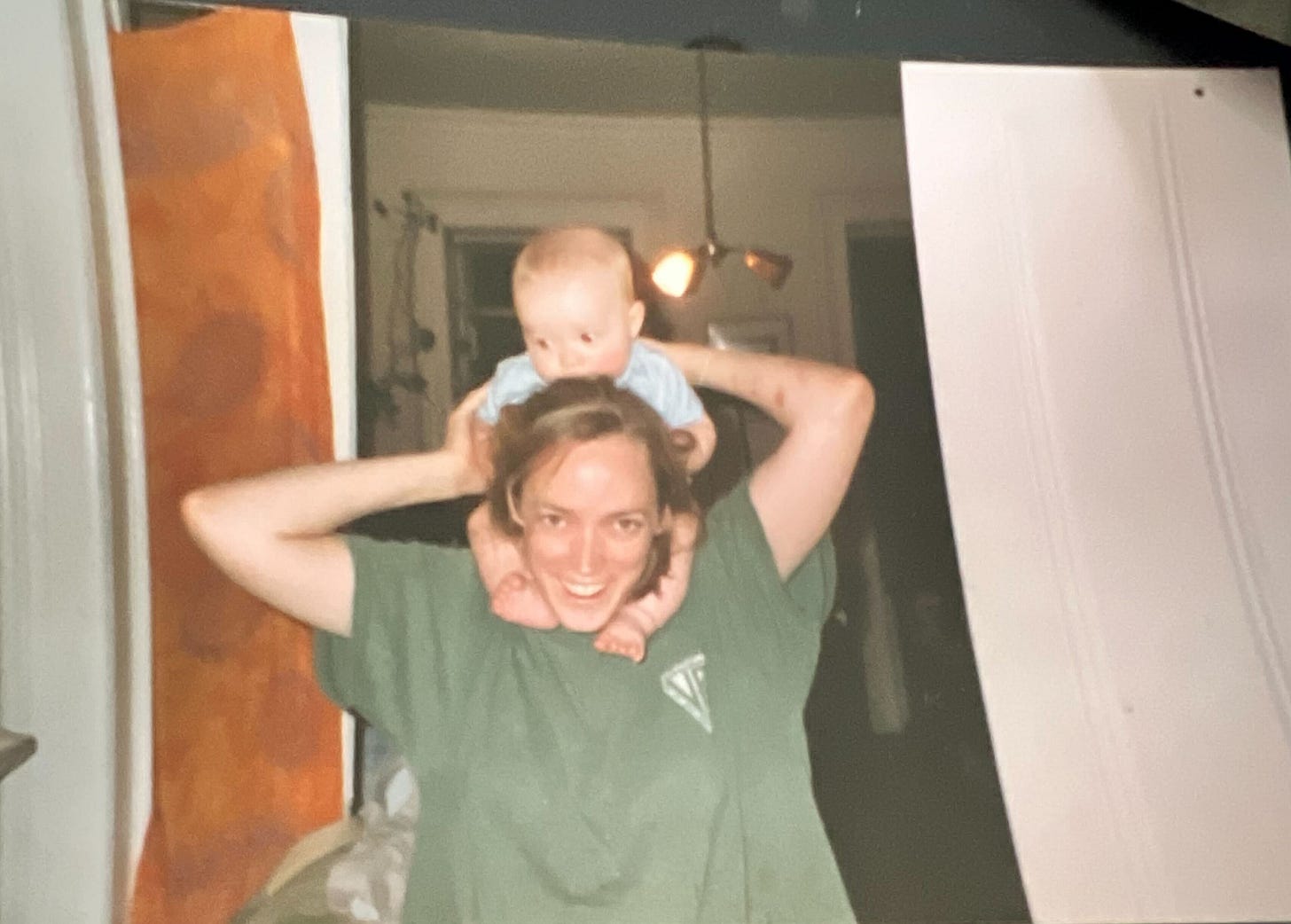

A lifetime ago, I watched from the second-floor window as my boyfriend cut tiles in the backyard of our little row house in Brooklyn. The saw whined sharply as it spewed tile dust into the ragged weeds. I was deeply frustrated. I’d known we would be doing this type of hard work on the fixer-upper we’d just bought on the shaggy border of Park Slope. But I’d always assumed we’d be doing it side by side. And yet there I was, marooned in the bedroom, nursing the baby to sleep.

I never meant to become a wife. When I was growing up in the ’70s, the daughter of two activist types who hoped to change the world, marriage sounded like a trap. Wives seemed sad and overwhelmed, like the always-pregnant Irish mom who lived around the corner from us when I was little. Or they were repressed and miserable, like the ones I read about in The Women’s Room, that classic 1977 novel beloved by the second wave feminists—who were busy deconstructing every idea foundational to family life, from gender roles to monogamy, aided and abetted by the hippies and iconoclasts. In Ptolemy Tompkins’s memoir about growing up in the ’70s, he describes the time his eccentric scientist father brought home a female grad student and announced to his wife and kids that marriage was a bourgeois institution, and thus henceforth Betty would be part of the family.

My parents weren’t that extreme, but they still wanted to take a sledgehammer to social norms. They both adhered to the blank-slate idea: that differences between men and women were socially constructed, and a little tweaking would solve the problem of disparate outcomes. My mother dressed my sister and I in overalls and Earth shoes, and if we got baby dolls or tea sets, it was with a hint of disapproval. Why would girls play at being mothers or wives when they could sit on the Supreme Court or fly to the moon? When I was in sixth grade, my mother gave me a framed print that said: A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle.

By the time I got to college, I’d sworn off the idea of ever being a wife. It wasn’t only about avoiding repressive gender roles. Every marriage I had known about as a child had ended in divorce. My grandparents were divorced before I was even born. The family weddings I went to throughout my childhood—the hippie gathering in a pine forest, the traditional ceremony in a church, the one in Boston where my uncle wore a yarmulke and broke a wineglass to marry a Jewish woman—all ended in divorce. Most of my friends’ parents got divorced, as did mine. Everyone got divorced.

In college, my friends shared my skepticism. One night, in a discussion about what we wanted out of life, a group of us laughed at a preppy, naive housemate who said getting married was a priority for her. The rest of us planned to have art careers, travel the world, write books, get law degrees, move to Manhattan or Paris. In comparison to the things we hoped for, being a wife seemed small and backward and insignificant.

If I could have sworn off men the way I sporadically quit eating meat or using politically incorrect language, it would have been easier. But I was wired to consort with the enemy. When I was 26, in the mid-’90s, I fell hard for a funny and intense artist named Chris. Another child of divorce, he had his own reservations about marriage; but perhaps because of our unstructured childhoods, we both craved the stability of monogamy. It turned out that even if I didn’t want to get married, I wanted something like marriage. But what?

So many of the tools and traditions for keeping couples together had been burned to the ground. I identified with the couple in Margaret Atwood’s stark little poem “Habitation,” in which she describes marriage as two people crouched at the “edge of the receding glacier,” where they are “learning to make fire.” Maybe every young couple feels this way, but surely our generation was the first one tasked with building such an essential vessel—that births and raises the next generation of civilization—from so much wreckage.

In our first year together, Chris and I worked side by side to scour and rehab the rundown apartment I occupied in then-gritty Williamsburg. When my roommate announced she was moving out, it made sense for Chris to move in. I remember confiding to a friend that I was nervous about this step. I had been in New York City for a year and had begun publishing essays. A temp job at a news agency had turned into a steady gig. Would I lose my independence? Shouldn’t I stay focused on my career?

I was right to worry: It turned out I loved living together. I loved it so much it made me a little uneasy.

I had a friend in the building who’d been raised by boho leftists, just like I’d been, and was pursuing a writing career, just like I was. Over wine one afternoon we admitted to each other—and it really felt like a taboo secret—that we liked cooking dinner for our boyfriends, sometimes even more than we liked our day jobs, where we did dreary tasks like filing paperwork or writing up marketing meetings. By the rules of our feminist upbringings, this felt like admitting we wanted to be scullery maids.

Even worse, I liked all sorts of domestic arts, like baking pies with fanciful decorations on the crusts. I often spent countless hours on outrageously female-coded projects, like creating a handwritten cookbook with silhouette cutouts for illustrations or sewing a quilt from felted wool sweaters or stitching traditional clothes for a fabric doll I’d made just because I found some caramel-colored velvet and had a vision. This was long before Instagram; at the time I knew very few women who pursued such small and irrelevant, such female, hobbies.

I couldn’t have imagined that one day, quite soon, countless women would publicize just this sort of hobby, thanks to the rise of social media—or that they would become associated with a new archetype, the tradwife. This fringe group of women builds brands and personas based on the kind of domestic projects I had been doing privately, almost in secret.

Perhaps the most famous among them, Hannah Neeleman of Ballerina Farm, has around 15 million followers on various platforms, where she shares videos of herself making homey meals from scratch, or getting dressed for church, or packing up the flowers that she and her husband sell. I’ve gone to her website a handful of times over the last few years, and every time I visit, there are more items for sale, ranging from protein powder to enamel mixing bowls to beef boxes. The trad wife influencers have been disparaged and scorned by the masses; but perhaps attaching economic value to female-coded domestic labor is a solution to the income disparities between men and women, which protest marches and feminist theory have failed to do.

Before we had kids, our solution for avoiding regressive gender roles was to follow the roommate model, splitting every bill and chore. Sure, I did more cooking, but Chris always helped, and what little housekeeping we did was equally shared with minimum discussion. He earned more from his job in the animation industry than I did as a freelance editor and writer, but we figured out a loosely proportionate system for paying bills. We did our laundry side by side at the laundromat. Four years into our relationship, even as we began hunting for a house to buy, we still had no plans to get married. Perhaps we would have continued like this indefinitely if not for a singular event. Two weeks after I turned 30, we became parents.

I assumed I’d go back to work when our son was a few months old, as seemed to be the norm in New York City. But this turned out to be impossible. First, I didn’t earn enough as an editor to justify day care or a nanny. But even more importantly, leaving that soft little creature who fit so snugly and easily into my arms—who burrowed his face into my neck and slept against my chest as if he belonged there—felt deeply, in my bones, wrong. So I stayed home.

Then we moved into that little row house, which needed work. Between the baby—who preferred me to Chris, and wouldn’t take a bottle—and the labor on the house, and our disparate incomes, the next several years would be an exercise in discarding so many of the beliefs and ideals I’d grown up with. If I’d given any thought at the time to that print my mother gave me, about needing a man like a fish needs a bicycle, I would have scoffed at it. I wanted to provide for this baby what he needed, which was me; to do that, I needed Chris, far more than a bicycle or anything else. There was just no way around this equation.

Around this time, a friend who had no kids mentioned that she would never let a man hold the door for her, on principle. I was by then maneuvering through public spaces weighed down with a baby, a stroller, and sometimes various shopping bags; I thought her view was ridiculous. I needed all the help I could get, and I was starting to notice that the principles of equity laid out by the feminists weren’t exactly working in my favor. I was working from home as an editor and writer, conducting DIY jobs on the house, nursing a baby, and running the household. So, women just did everything now? And since men couldn’t help with birthing and nursing, and the babies all seemed to want their moms more than their dads, men were just off the hook for half the labor in the house? I started passing up on some of the male-coded jobs I’d always tried to do, on principle.

In chaotic times, ideals give way to the most practical, efficient way to get through the day. Chris and I fell into doing the tasks that made the most sense. Working on our house, for example, I couldn’t contribute the way I’d thought I would. This was frustrating at first, but sometimes it was just fine. For example, we had salvaged a cast-iron farmhouse sink that needed to be carried up to the third floor, a job I wasn’t looking forward to. Fortunately, Chris was able to get a friend to help him. They hoisted and heaved this massive sink up the stairs, grunting and cursing as they went, as I held the baby and watched. Let the men do their work, I thought grandly.

Chris and I were realizing that building a family was hard, nearly impossible, and we began looking for all the structure we could get. When our son was 2, we finally got married in Brooklyn Bridge Park, looking across the East River toward the Twin Towers. The words boyfriend and girlfriend had become entirely inadequate; and it felt like it was time to grow up. But though I was happy to be married, it didn’t solve the problems I’d hoped it would. Life was still chaotic and messy. There were still too many chores, no matter who did them.

And then we added to our workload. In 2010, when my kids—by then we’d had another child, a daughter—were 6 and 11, we moved upstate and began running a small hobby farm. Here’s where the last of my feminist principles fell apart. There is too much work to do on a farm to bother fussing over who does which jobs. We do what we’re good at. The fact that many jobs sort automatically into classic sex roles—by virtue of biology or preference—is simply reality.

I can’t climb a ladder higher than about 10 feet, while Chris is unfazed by heights. He once repainted a metal-shingle barn roof in the August heat, 20 feet off the ground. When he came in for lunch looking like he’d walked through an inferno, I was just fine with my contribution: offering him a glass of lemonade and an egg-salad sandwich. He also does all the shooting and killing and culling of animals, along with the dicey rescues. When we found a starling embedded in a chicken wire panel—or a fierce yellow-eyed owl glaring out at us from inside a Havahart trap—he was the one to wrangle the bird out and back into the wild.

I do hard work all the time, pushing five-foot-high hay bales across the yard, hauling five-gallon buckets of water in each hand, carrying 50-pound bags of feed, corralling reluctant sheep or goats into a stall. But the work Chris does is harder, because he is significantly stronger. He is also bolder, steadier, and more willing to do grueling tasks. Like most men, when he hears about a problem, he wants to solve it.

As a college student I used to bristle at my grandmother’s constant sexist stereotypes. “When your brother gets here, I’m going to ask him to bring that heavy box inside,” she’d say. I’d indignantly remind her that I was strong, too, and I’d show her, hoisting the box and hauling it to wherever she wanted. But now I imagine my grandmother and her sister giving each other side-glances and shaking their heads at my swagger. Of course you can do it, I imagine them saying. That’s beside the point. Why would you give yourself extra work while taking away the job that men feel good doing for you?

Any kind of successful partnership relies on finding who does what best and then giving them leave to do it. Like most women, I’m probably better at organizing the family calendar or managing a crisis than most men, and I liked being the primary decision-maker on the medical and educational needs of our kids. It has become fashionable for women to complain about this “emotional labor,” but why wouldn’t I gladly contribute these skills and talents to our family? Besides, there are other kinds of emotional labor, which men tend to excel at. When I get caught up in anxious overthinking, my husband’s wry, unflappable response is stabilizing.

I stand by a lot of the feminist lessons I learned as a child. Of course women can sit on the Supreme Court and be astronauts or physicists or lawyers. Of course we can survive without men. But getting married, being a wife, being a mother, is not a step back in time, or a surrendering of ground. It’s actually the best part of my life.

After 25 years as a wife, I sometimes feel like my whole family has walked through an inferno—and survived. And I’ve come to realize that marriage is too difficult—and deep and important and personal—to be hampered either by sexist stereotypes, or the doctrines of the people who want to smash them to smithereens. Make quilts and pies if you feel like it. Tar the roof. Fix the water pipes. Have the babies and take turns carrying them and feeding them—or send your husband off to work while you stay home making videos of your sourdough journey—however your family works it out. That’s the best thing about marriage: You get to create your own world at the edge of the glacier.

If you loved this essay, catch up on Larissa’s previous column: “Dreaming About Going Back to the Land? I Did It.”