For the past decade, social psychologist Jonathan Haidt has been explaining the human condition to us better than just about anyone else.

He did it first with his book The Righteous Mind, which helped explain why people are so passionately divided over politics and religion, and which also made the argument that human beings are fundamentally religiously inclined creatures.

Then, Haidt did it again with The Coddling of the American Mind, which he co-wrote with Greg Lukianoff. The book laid out why kids today—especially on college campuses—have become so intolerant of opinions that conflict with their own, and how this intolerance has impacted the country and our culture.

Now he’s done it once more with his new book, The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness.

This time, Haidt explains what has confounded so many parents: Why are kids today more anxious than ever, more depressed than ever, more risk-averse than ever, lonelier than ever, and less social than ever?

It’s pretty simple, he argues: we changed childhood.

The mass migration of childhood from the real world into the virtual world has completely changed what it means to be a kid. In replacing free play and quality time with friends with the isolation of screens and phones, we instigated what he calls “the great rewiring.”

Haidt argues that “childhood was rewired into a form that was more sedentary, solitary, virtual, and incompatible with healthy human development.”

A few weeks ago, I had a conversation on our podcast Honestly with author Abigail Shrier about some of these same topics, many of which she covers in her best-selling new book Bad Therapy. It sparked a passionate response (and a lot of letters to the editor, some of which we published in The Free Press.)

Jon comes at this from a different angle—and one we think is very much in conversation with Abigail’s work.

This topic is so important—and not just for those of you who are parents. It matters to anyone who cares deeply about our future, because that future is inextricably linked with how we raise the next generation of adults.

Click below to listen to my conversation with Jonathan Haidt on Honestly, where he discusses the problem and what we can do to fix it. And read on for an exclusive excerpt from his new book. —BW

Suppose a salesman in an electronics store told you he had a new product for your 11-year-old daughter that’s very entertaining—even more so than television—with no harmful side effects of any kind, but also no more than minimal benefits beyond the entertainment value. How much would this product be worth to you?

You can’t answer this question without knowing the opportunity cost. In Walden, his 1854 reflection on simple living, Henry David Thoreau wrote, “The cost of a thing is the amount of. . . life which is required to be exchanged for it, immediately or in the long run.”

What the smartphone user gives up is time. A huge amount of it.

Around 40 hours a week for preteens like your daughter. For teens aged 13 to 18, it’s closer to 50 hours per week. Those numbers—six to eight hours per day—are what teens spend on all screen-based leisure activities.

These numbers vary somewhat by social class (more use in lower-income families than in high-income families), race (more use in black and Latino families than in white and Asian families), and sexual minority status (more use among LGBTQ youth).

I should note that researchers’ efforts to measure screen time are probably yielding underestimates. When the question is asked differently, Pew Research finds that a third of teens say they are on one of the major social media sites “almost constantly,” and 45 percent of teens report that they use the internet “almost constantly.” So even if the average teen reports “just” seven hours of leisure screen time per day, if you count all the time that they are actively thinking about social media, you can understand why nearly half of all teens say that they are online almost all the time. That means around 16 hours per day—112 hours per week—when they are not fully present in whatever is going on around them.

At that point, knowing all this, wouldn’t you walk out of the store?

There is a huge opportunity cost to children and adolescents when they start spending six, or eight, or perhaps even 16 hours each day interacting with their devices. Here are the four foundational harms of a phone-based childhood. There are many more, but these four are the most direct consequences of the “great rewiring of childhood” that took place between 2010 and 2015.

Harm #1: Social Deprivation

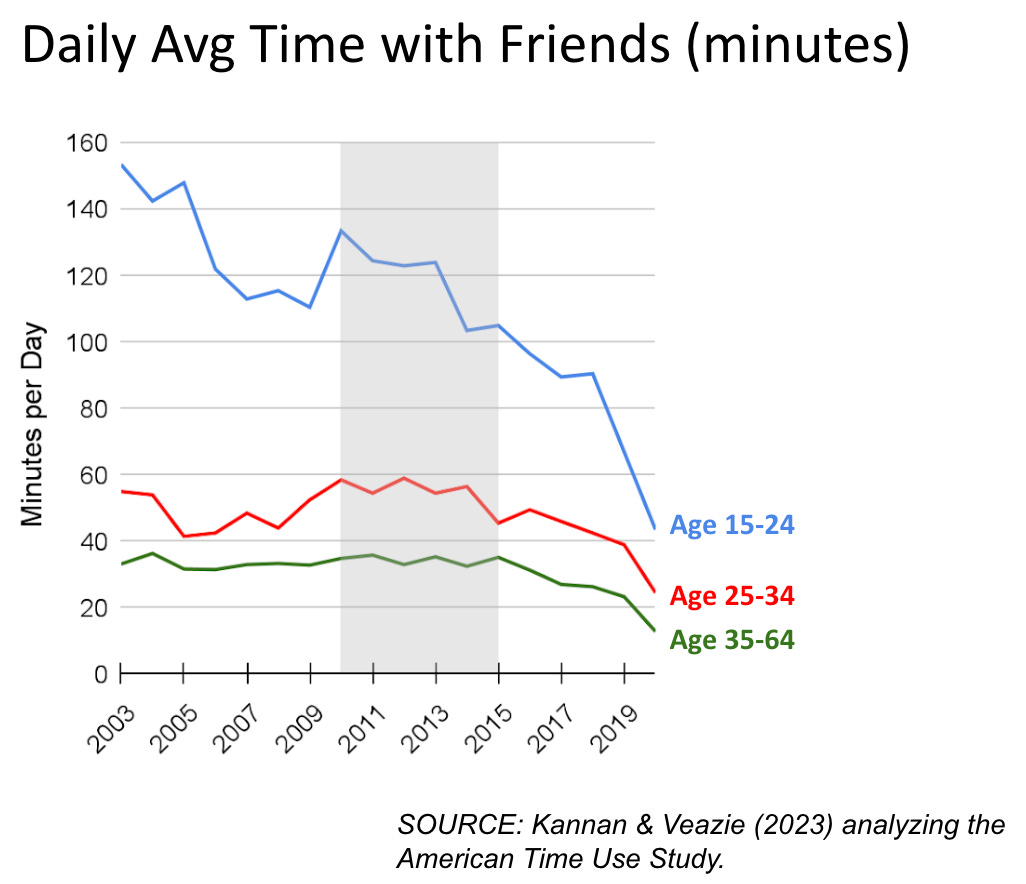

Children and adolescents need a lot of time to play with each other or just hang out, face-to-face, to foster social development. The percentage of 12th graders who said that they got together with their friends “almost every day” dropped sharply after 2009. You can see the loss of friend time in finer detail in figure 5.1 (below), from a study on how Americans of all ages spend their time.

The figure shows the daily average number of minutes that people in different age brackets spend with their friends. Not surprisingly, the youngest group (ages 15–24) spends more time with friends, compared with the older groups, who are more likely to be employed and married. The difference was very large in the early 2000s, but it was declining, and the decline accelerated after 2013. The data for 2020 was collected after the Covid epidemic arrived, which explains why the lines bend downward in that last year for the two older groups. But for the youngest age group there is no bend at 2019. The decline caused by the first year of Covid restrictions was no bigger than the decline that occurred the year before Covid arrived.

In 2020, we began telling everyone to avoid proximity to any person outside their “bubble,” but members of Gen Z began socially distancing themselves as soon as they got their first smartphones.

Of course, teens at the time might not have thought they were losing their friends; they thought they were just moving the friendship from real life to Instagram, Snapchat, and online video games. Isn’t that just as good? No. As Generations author Jean Twenge has shown, teens who spend more time using social media are more likely to suffer from depression, anxiety, and other disorders, while teens who spend more time with groups of young people (such as playing team sports or participating in religious communities) have better mental health.

It makes sense. Children need face-to-face, synchronous, embodied, physical play. The healthiest play is outdoors and includes occasional physical risk-taking and thrilling adventure. Talking on FaceTime with close friends is good, like an old-fashioned phone call to which a visual channel has been added. In contrast, sitting alone in your bedroom consuming a bottomless feed of other people’s content, or playing endless hours of video games with a shifting cast of friends and strangers, or posting your own content and waiting for other kids (or strangers) to like or comment is so far from what children need that these activities should not be considered healthy new forms of adolescent interaction; they are alternatives that consume so much time that they reduce the amount of time teens spend together.

Even when teens are within a few feet of their friends, their phone-based childhoods damage the quality of their time together. Smartphones grab our attention so powerfully that if they merely vibrate in our pockets for a tenth of a second, many of us will interrupt a face-to-face conversation, just in case the phone is bringing us an important update.

It’s painful to be ignored, at any age. Just imagine being a teen trying to develop a sense of who you are and where you fit in, while everyone you meet tells you, indirectly: you’re not as important as the people on my phone. And now imagine being a young child. A 2014 survey of children ages 6–12, conducted by Highlights magazine, found that 62 percent of children reported that their parents were “often distracted” when the child tried to talk with them.