The Free Press

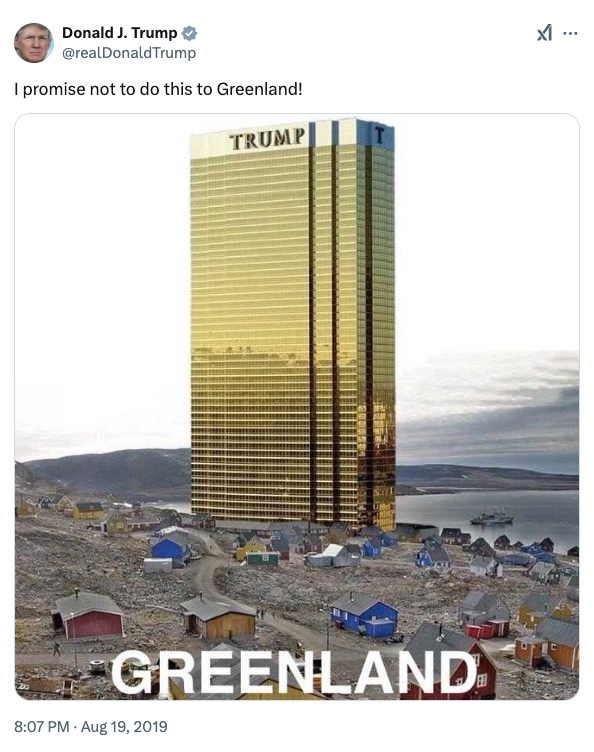

The idea of the United States buying Greenland isn’t new. And it’s certainly not new to Donald Trump, who several times during his first term made public statements—jokes and memes included—about wanting to acquire the gigantic landmass in the Arctic that is today part of Denmark.

Since winning the presidential election in November, Trump has resurfaced his intention to pursue an acquisition of Greenland, and added in Canada and the Panama Canal for good measure. Announcing his choice for ambassador to Denmark, Trump said: “For purposes of National Security and Freedom throughout the World, the United States of America feels that the ownership and control of Greenland is an absolute necessity.” A few days later on Truth Social, Trump posted a Christmas greeting “to the people of Greenland, which is needed by the United States for National Security purposes.” Trump added that Greenlanders “want the U.S. to be there” and that “we will!”

In 2019, when then-President Trump first floated the idea of acquiring Greenland, he tasked his national security adviser, Ambassador John Bolton, with figuring out the specifics. I called up Bolton, 76, to ask him what he thinks about Trump revisiting the idea. (Bolton resigned in September 2019, and had a public falling-out with Trump. A year later, as Bolton published his memoir The Room Where It Happened, Trump lashed out at Bolton, calling him a “disgruntled boring fool who only wanted to go to war,” and reportedly attempted to halt the book’s publication.)

The following is lightly edited for clarity and concision.

Adam Rubenstein: What’s the case for making Greenland part of the United States?

Ambassador John Bolton: You need to make a case to make it part of the United States. That is an option—although given the way it’s been handled by Trump since 2019, not much of an option is left of it.

But the point is Greenland is intimately connected with our security for a lot of reasons and has been visibly since World War II, after the Danish government fell, to protect the North Atlantic convoys and our own interests against the Nazi threat.

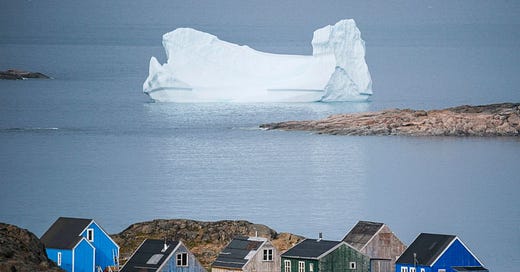

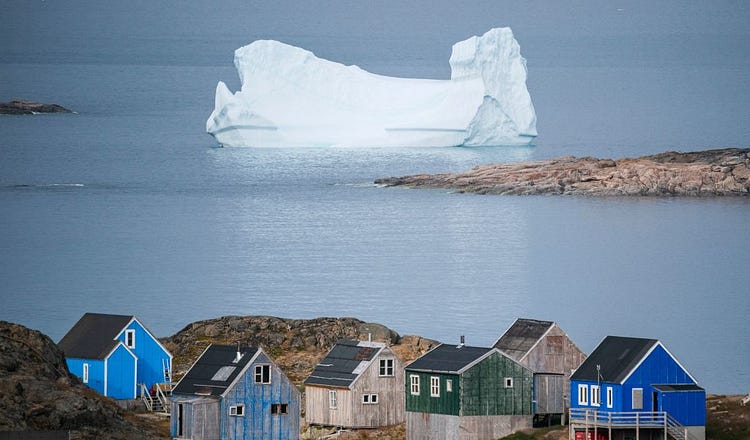

After World War II, we built an Air Force base at Thule (now the Pituffik Space Base in Greenland’s Northwest). It was part of the extended DEW line, the “distant early warning” system against Soviet missile launches. If you look at a map of the Arctic Ocean, there are five countries that have claims of economic zones and so on in the Arctic: the U.S., Canada, Denmark, Norway, and Russia.

Four of them are NATO members, and Greenland and its territory and its economic zone are a critical part of that. And we know from repeated efforts by the Chinese to extend their influence, they want to become an Arctic power. With global warming, that Northwest passage becomes a more viable maritime route. They want to be part of it. So given Greenland’s geographic proximity to the United States, and everything else I’ve stated, it’s obviously a strategic interest.

Just a couple facts: Nuuk, the capital of Greenland, is closer to Washington than it is to Copenhagen. So if you look at a map, it’s part of the North American landmass, and that makes it a vital security interest for the United States.

AR: I read that following a meeting with the businessman and philanthropist Ronald Lauder in 2019 that getting Greenland was suddenly on Trump’s radar, and that you then had an adviser—Fiona Hill—convene a working group on acquiring Greenland or making some sort of deal with Denmark for Greenland, and that it produced some “options memo.”

JB: Well, I don’t remember much of a group. I asked Fiona to take a look at some of the possibilities, and I don’t remember an options paper. I asked Fiona to take a look at what might be possible. And this was not some crash project.

I remember hearing from Trump on this, which I later learned or figured out came from Ronald Lauder. But Trump first raised it with me in 2019. The first kind of work product that I remember would’ve been in the spring, which raised the possibility of using what’s called the Defense of Greenland Treaty between the U.S. and Denmark, which was written in 1951. It’s been amended since then, I think during the George W. Bush administration. But basically, it’s the framework for U.S. forces that were stationed in Greenland after 1951.

So that was a bit where we might’ve had discussions that don’t get into larger questions of Greenland’s status, or who has sovereignty over it.

And there are other possibilities that occurred to me: commonwealth status, like Puerto Rico. Joint condominium with Denmark. Independence but with a Compact of Free Association with the United States like Palau, Micronesia, and the Marshall Islands.

There are a lot of possibilities. But they never got anywhere, because Trump talked about everything publicly, and the whole thing blew up.

AR: Was there ever a dollar amount attached to these ideas?

JB: No, no, no.

AR: It never got that far?

JB: As far as I know. I mean, after I left, I can’t speak to, but it never approached that point.

AR: So in your view, it became public before any private dialogue, before the Danes ever had an idea that the U.S. or Trump would be interested in it, or an offer would come their way?

JB: Trump was obviously talking about it to people. And I think sometime in August of 2019—and I remember the time frame very, very vividly, because I resigned on September 12. So this was all right at the end of my tenure.

But somehow there were press stories about it. It was coming to a head because Trump was scheduled to go to the 80th commemoration of Germany’s invasion of Poland. And because there was some idea that Melania Trump wanted to go to Denmark, they had scheduled a visit to Denmark after the ceremony in Warsaw on September 1.

I’m getting ahead of the story, but it turned out Melania didn’t want to go to Denmark. I remember being in a conversation—Trump having a conversation with her on the speakerphone, either in the Oval Office or back in his little dining room, where she said, “I don’t know why people keep saying, I want to go to Denmark. If you want to go to Denmark, I’ll go with you, of course, but I don’t want to go to Denmark.”

But anyway, it was after the September 1 trip that people’s attention began to focus, because that would have been an opportunity to at least discreetly raise the issue with Denmark, where it’s an extraordinarily sensitive topic.

But somehow, it got out that Trump was interested in buying Greenland. This all ties into the Biarritz G7 Summit. I did go to Biarritz, France, at the end of August, a day or two before Trump, to help get things in order. And then my plan was to go from Biarritz to Denmark before the September 1 ceremony in Poland—then to talk quietly to the Danes about Greenland in anticipation that Trump would be visiting on September 2 and 3.

So all of this starts blowing up at the end of August. And at some point, before the G7 Summit, the Danish prime minister said it was absurd, which may have been produced by Trump saying something public.

But after Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen said this, Trump called her “nasty” and said she was blowing off the United States, which he didn’t like, not showing respect. Calling her “nasty” is not the way I would normally start off a negotiation about buying a chunk of territory as big as Greenland, leaving that aside.

So then, when we find out Melania really doesn’t want to go to Denmark, we canceled the trip, which was fine with me. We weren’t ready yet. We hadn’t talked to the Danes about it, except Trump speaking publicly.

But my plan at that point was still, I would go to Copenhagen and very quietly talk about Greenland’s security. And I told Trump I planned to do this. And even though he wasn’t going, I would go anyway. And he said, ‘No, don’t go. Because I’ve canceled my trip, it looks like we’re trying to beg for their favor again if you go.’ But Trump was adamant. So I never went.

AR: Trump hasn’t taken office yet, and he’s already saying, I guess we can assume they’re jokes, in part, about “Governor Trudeau of the great state of Canada,” and about reclaiming control of the Panama Canal. Do you think these are serious proposals?

JB: Well, who knows with Trump what’s serious and what’s not? If he calls the Danish prime minister “nasty” again, that probably won’t have a good effect. But look, this is an important matter of security for the United States. It is sensitive and delicate, both for the inhabitants of Greenland, who don’t like the idea of being sold without their consent and for the country. So negotiating in public with your friends like this just makes the ultimate objective—whatever it is—harder. And Trump didn’t understand that in 2019. And apparently he doesn’t understand it today.

AR: If you were advising him today, is there a pathway you’d recommend he’d take?

JB: Yeah, close his mouth.

AR: And then do what?

JB: Try a little private negotiation. Send one of your trusted advisers incommunicado to Copenhagen to talk to the prime minister. Send your national security adviser for private discussions. Don’t have any press conferences. Just talk to ’em. How about that? Find out what their current state of mind is before you tell ’em what you’re going to do to ’em.

AR: On that path, where do you see those discussions leaving things? What do you think the U.S.’s goal should be in that process?

JB: There are multiple ways I think we can satisfy our national security interest less changing the current sovereign relationship of Greenland to Denmark. Former secretary of state Jim Baker always used to say to me, “Keep your eyes on the prize. The prize is not sovereignty. The prize is security.”

AR: Do you think that would cut it for Trump?

JB: No, I don’t think so.

AR: So for him, you think it’s less about security and more about a shiny acquisition?

JB: It’s real estate. He wants to put a Trump casino in Nuuk.

AR: Did that ever come up in your conversations?

JB: Trump Nuuk, how is that for posterity? Trump Nuuk. A Trump Tower, too.

AR: When you were talking about this with him, did that ever come up?

JB: I think he did a tweet on Greenland’s real estate. I’m serious, I think he did.

AR: Did it come up in your discussions that it was more about the land for him than any security interest? Territorial acquisition for its own sake, rather than national security?

JB: Well, I explained it to him, but that’s not what—I don’t think he understood that.