The Free Press

If there’s one thing you can count on in politics, it’s that both sides will let the other dictate their own messaging. It’s an inescapable condition. Watch a fight over any particular issue, observe the caricature that side A makes of side B’s position, and then watch side B dutifully adopt that as their actual position, as if by magic. It’s remarkable! I guess if the person you hate keeps saying that you’re X, you start to want to become X to stick it in their eye. We’re getting a really strong dose of that right now, as conservatives (being the stupid oafs they are) have started attacking any efforts against racism or bigotry as “DEI,” and liberals (being the feckless and lazy scolds they are) have decided to join them in doing so, to own Drumpf or whatever. Everything is stupid and I hate it here.

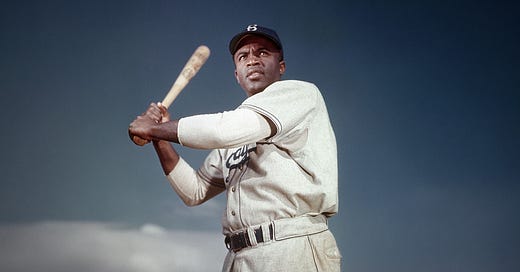

The Trump administration, being both maliciously destructive and endlessly bumbling, recently took down a government web page honoring Jackie Robinson, the Brooklyn Dodger who broke baseball’s color line. Sports personality Nick Wright has drawn a lot of praise by declaring that Jackie Robinson was a “DEI hire,” and that proves that DEI is good. Which, first, suggests that Nick Wright doesn’t know the basic terminology or history of the American civil rights movement.

Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947, which was a good 60-ish years or so before modern DEI was ever developed. Yes, Elon Musk and his goon squad use DEI to refer to any anti-racist effort. But so what? Why would we follow him? Why do people always, always, always do this—embrace the frames conservatives put on them in an effort to show that they’re Good and conservatives are Bad? DEI is not the sum total of America’s history of civil rights, and conflating this weird 21st-century administrative approach to racism with the long fight for equality is profoundly unhelpful. There have always been different approaches and camps and historical moments within the fight against discrimination and identity-based inequality. Of course there have been! Does Wright know that? Does Mina Kimes? Does Stephen A. Smith? It’s not clear.

Second, Wright’s speech shows that people won’t just conflate DEI with the broad effort against racism, but with any particular part of it. Wright refers to Robinson as a “DEI hire,” trying to reappropriate the term to show that DEI is good, actually. But “DEI hire” is a pejorative used to suggest that someone who gets a job is unqualified for the position. It’s an allegation about a particularly ugly view of affirmative action. A DEI hire, to the people who use the term, is someone who has been advanced professionally despite incompetence because of a desire to increase diversity. Is that a problem Jackie Robinson had? Jackie Robinson, 1947 Rookie of the Year and 1949 MVP? Jackie Robinson, who had a career .410 on-base percentage (OBP)? That Jackie Robinson? I join Wright in arguing that the left should support diversity programs by acknowledging that they work as intended—that is, by not shrinking away from saying that some people get opportunities they wouldn’t have absent those programs. That’s the whole point! But black baseball players weren’t excluded from baseball because they weren’t good enough, and they weren’t let in out of charity. On the contrary, they had to be better than other players to get a chance. That’s not affirmative action, it’s not DEI hiring, and I simply do not understand the utility of this constant conflation of different ideas and programs.

The terms you might use to refer to Robinson’s courageous efforts are desegregation or integration. Those are good words, proud words with proud histories. Ditching them and embracing the vastly more fraught, new, and vague term DEI, because you want to show the world that you aren’t Trumpy, is just such a perfect demonstration of why liberalism struggles so much in 2025. Conservatives act; liberals react, usually by complaining.

When people say DEI, or diversity, equity, and inclusion, they’re referring to a profoundly 21st-century school of corporate identity progressivism. It’s a method of (appearing to) fight bigotry by raising the visibility of superficial diversity in the setting of the corporation, university, government agency, or nonprofit that’s implementing the DEI program; by instituting complex codes regarding language and symbolism that could potentially refer to identity categories; by rewriting the rules, in a corporate handbook or student code or similar; and in general by imposing a particular vision of race, gender, sexual orientation, and disability that’s filtered through abstruse and obscure theories developed in humanities departments in the past quarter century. Don’t think of old civil rights slogans like “Jobs and Justice”; think of terms like dysconciousness, centering, and misogynoir. Don’t think of sit-ins and marches; think of posters about black excellence. Take civil rights in the most white-collar direction possible, anti-racism for the age of self-care, and you will have DEI.

Like liberalism in general, DEI is fundamentally a managerial philosophy—it’s built on the notion that injustice is ultimately a kind of HR violation that can always be remedied from above because the benevolent institution (corporation, nonprofit, etc.) has unfettered power to respond to misdeeds. As a managerial philosophy, it exclusively seeks to reform institutions, never to tear them down, because it is the institution that is perceived to hold all power; indeed, managerial philosophies cannot comprehend of a world outside of the institution. There is no outside-the-institution, so therefore filling out form 51-J to report a Nonconsensual Triggering Event must be an effective remedy. This is part of why liberalism is so impotent in the present moment, because liberals cannot conceive of a vision of politics that isn’t fundamentally about asking Big Mommy to come spank the bad guys. And it’s why DEI is so bereft of solutions that could actually solve anything; you rewrite corporate handbooks and hold sensitivity trainings because your ethos fundamentally prevents you from doing things that might actually work. The institution can conceive only of initiatives that further the institution, but institutions are fundamentally part of the problem.

Two core things to understand about DEI, then. One, it’s very new, a profoundly 21st-century ideology even if the term had some limited use before this century. It is an absolute and utter anachronism to ascribe DEI to racial politics of the past. Frederick Douglass had nothing to do with DEI and neither did W.E.B. Du Bois and neither did Booker T. Washington and neither did Mary McLeod Bethune and neither did Medgar Evers and neither did MLK Jr. and neither did Fred Shuttlesworth. This effort to insist that every beloved leader or argument or policy or struggle has been retroactively branded with DEI is, again, bizarre.

Second, like all corporate efforts, DEI fundamentally serves the needs of the corporation, and thus actual diversity, equity, and inclusion are secondary goals at best. DEI programs are part of institutions and thus, they serve those institutions. I don’t doubt that the average employee with a DEI-related job believes in what they’re doing, but that’s sort of the point, right—the very structure of the thing ensures that good intentions are ultimately subservient to the needs of the institution. Indeed, the existence of DEI programs can have the effect of making it harder for people of color to sue on racial or gender discrimination grounds! If an ex-employee sues their former employer on grounds of a racially or sexually hostile atmosphere, or similar, that employer will have the ability to present as evidence the rewritten employee handbook, the highly functional site where employees can submit complaints about insensitivity, the Black History Month posters adorning the walls. DEI enables corporate counsel to say, hey, we do care about making this a workplace free of racism/sexism/ableism, and we’re putting our dollars behind it. In this way, an entirely abstract pursuit of social justice gets in the way of actual people from marginalized groups seeking compensation for hostile work environments.

And, of course, there’s the bigger issue that none of this shit appears to work for anyone’s benefit except for a small guild of “anti-racism educators.” From a 2020 article in The New York Times Magazine:

Frank Dobbin, a Harvard sociology professor, has published research on attempts, over three decades, to combat bias in over 800 U.S. companies, including a 2016 study with Alexandra Kalev in the Harvard Business Review. . . . Dobbin’s research shows that the numbers of women or people of color in management do not increase with most anti-bias education. “There just isn’t much evidence that you can do anything to change either explicit or implicit bias in a half-day session,” Dobbin warns. “Stereotypes are too ingrained.”. . . . He noted that new research that he’s revising for publication suggests that anti-bias training can backfire, with adverse effects especially on Black people, perhaps, he speculated, because training, whether consciously or subconsciously, “activates stereotypes.” When we spoke again in June, he emphasized an additional finding from his data: the likelihood of backlash “if people feel that they’re being forced to go to diversity training to conform with social norms or laws.”

This is all that should matter: There’s no reason to believe that DEI programs make people less racist or sexist or whatever. How could they? Who really thinks that we can reduce the amount of ambient bigotry in the universe with workshops? One of the bizarre elements of the recent history of American racial politics lies in the tension between the immense racial pessimism offered by many commentators and the anodyne, corporate-friendly solutions they suggest.

Please, if we’re going to find a little hope in these incredibly dispiriting times, we need to think clearly and argue effectively. DEI is a very specific, highly contextual vision of progress; it could have developed only in the very odd context of the 2010s and under the very specific conditions of corporate America. There’s no reason to believe that it’s been of help to anybody, and it should not be conflated with the far nobler history of our civil rights movement. Even if—especially if—conservatives are the ones who first did the conflating.

This piece originally appeared on Freddie deBoer’s Substack.

Is baseball still a national treasure, or has it gone the way of rotary phones and dial-up internet? Our own Will Rahn and Joe Nocera debate America’s pastime in their piece, “Does Baseball Suck?”