The Free Press

When you read about the mineral agreement at the heart of negotiations between the U.S. and Ukraine, you might be left with the impression that the deal, in which the U.S. would gain the rights to a stream of profits from the sale of Ukrainian minerals—everything from rare earths and lithium to other newly mined resources—is totally unprecedented.

Some frame this as a form of expropriation or extortion, imperial in its scope. Others ask questions along the lines of: “Would Franklin D. Roosevelt ever have asked something like this of Churchill?!”

To which the answer is: very possibly, yes.

We know as much because something quite similar did happen before. So let’s travel back in time to early 1941—Britain’s darkest hour. As most of the continent succumbed to Hitler and Churchill clung doggedly on, a handful of men gathered in the White House to discuss what they could expect to plunder from the UK in exchange for economic support.

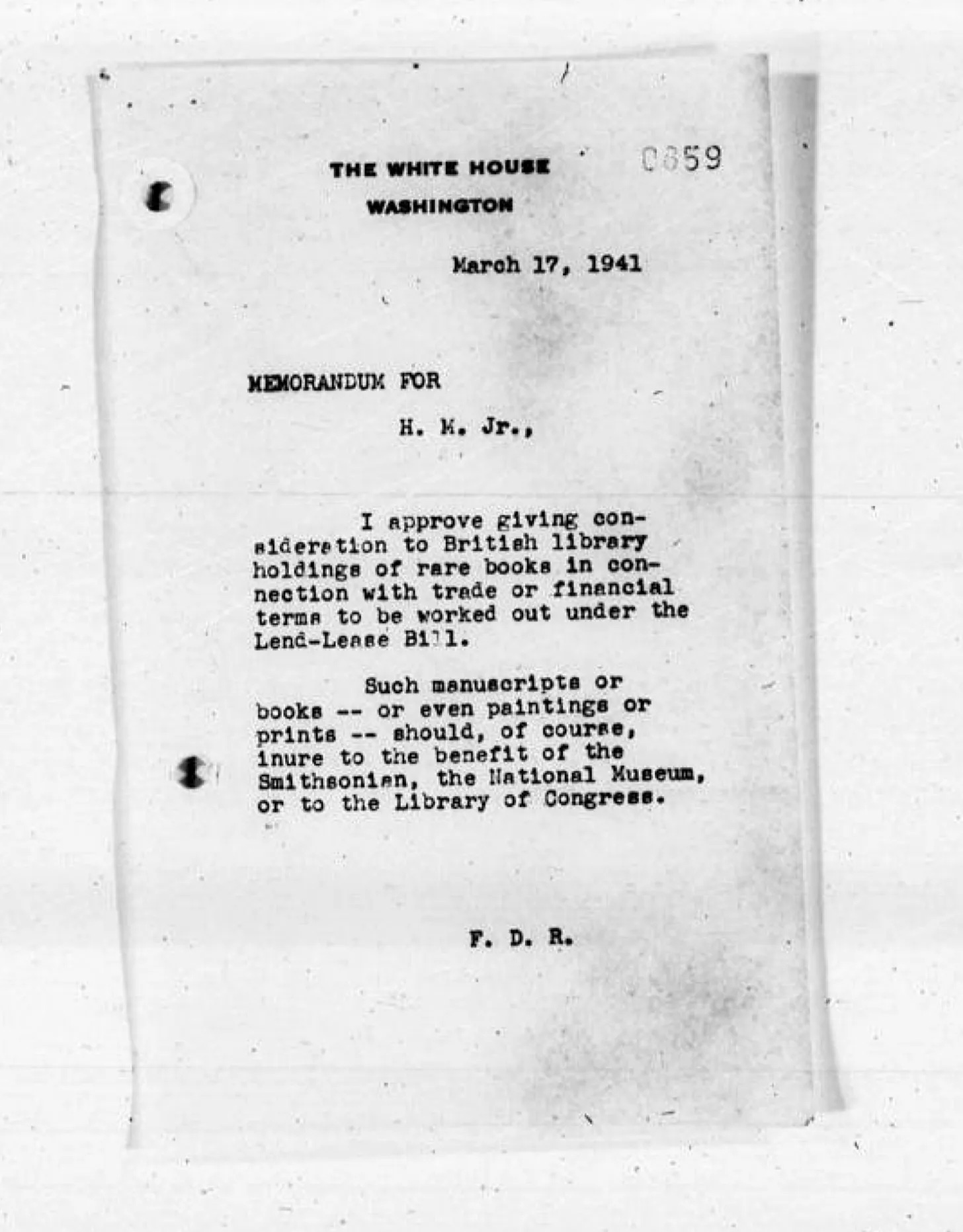

One idea was to take possession of the crown jewels. Another was that Britain should be forced to share Hong Kong with America. FDR went so far as writing a memo to his Treasury secretary asking him to look into getting hold of rare books and paintings from the British Library for the Smithsonian or the Library of Congress.

The president was formulating Lend-Lease, the set of loans and support that would keep Britain afloat and fighting over the coming years—a package described by Churchill as “the most unsordid act in the whole of recorded history.” Yet there is a forgotten side to that history, one that is worth recounting today as Ukraine gets close to signing this deal with America—committing it to vast repayments for aid in the form of mineral contracts in future years.

In case you think I’m making this up, below is the memorandum FDR sent to Henry Morgenthau, his Treasury secretary, about taking books and artworks from the British Library in exchange for Lend-Lease.

Nor were the crown jewels and precious books and artworks the only items to come up in the discussions about “considerations” for Lend-Lease aid. Another asset pondered by the Americans was the Magna Carta. Actually, British officials, conscious of the extraordinary generosity of American aid, pondered volunteering the Magna Carta themselves. One copy from Lincoln Cathedral was on tour in the U.S. at the time. “May we give you—at least as a token of our feelings—something of no intrinsic value whatever: a bit of parchment, more than seven hundred years old, rather the worse for wear,” wrote a Foreign Office official in a memo. “You know what it means to us; we believe it means as much to you.”

Of course, the Lincoln copy of the Magna Carta was returned to England. The crown jewels stayed in Britain too (some of the prize gemstones were stored in biscuit tins in Windsor Castle). But don’t be fooled into thinking Lend-Lease came entirely for free. The UK was forced, under some duress from the Americans, to sell one of the prized corporations of the chemicals sector. American Viscose, the man-made fabric company, was forcibly sold off by its owner Samuel Courtauld for around $50 million: less than half its estimated value.

But perhaps more significant than any strict repayment agreement were the principles Britain agreed to sign up to when taking Lend-Lease support. Most significantly, the UK signed up to Article VII of Lend-Lease, which committed it to free trade and to helping repair the international monetary system after the war. And since this meant dismantling the imperial preference system, that made it nearly impossible for Britain to maintain its empire after WWII.

Most people have forgotten about Article VII these days, but at the time it represented an extraordinary economic sacrifice for Britain, signed up to with gritted teeth and bemoaned for much of the war.

In the event, Lend-Lease was structured in a way that gave the president a wide discretion about actual repayments. Broadly speaking, it was left up to FDR. And so on the war went, Lend-Lease playing a key role in helping Britain defend itself from the Nazis. But then, in 1945, FDR died and everything changed. Harry Truman had a very different attitude. Within days of the Japanese surrender, Lend-Lease was cut off—far more abruptly than anyone in the UK had expected. Suddenly any support for Britain, now a civilian country, would have to be repaid, something that was pretty disastrous for the war-torn country.

When, eventually, the UK negotiated a postwar loan with America, the terms were far more onerous than expected. This might have had something to do with the fact that the main negotiator for the British side, John Maynard Keynes, was in such poor health he was dosed up on a heart medication whose main side effect was that it was a truth serum. But it was just as much a product of a more hostile White House, determined now not to provide any more financial assistance to the UK than was necessary.

In a sense, this mirrors the experience Ukraine has had in the past six months, as one president, inclined to provide almost limitless amounts to the country, was replaced with another president with a different international policy and a determination to withdraw American support.

This time around in Ukraine the amounts given by the U.S. are a tiny fraction of Lend-Lease. Nor are there any crown jewels to barter, so the U.S. is instead aping China, which has for decades been trading aid and infrastructure for investments in mining companies, especially in African nations like the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Ukraine has minerals (although perhaps less world-changing amounts than some might assume). So in much the same way as the greatest assets the UK had to trade back in the 1940s—beyond the crown jewels—were its international businesses like American Viscose and the Empire, Ukraine’s best assets might be seen as its minerals and its NATO ambitions. Both are now on the block.

None of this is to say the deal is proportionate, or to guess who it most benefits (it will be some time before we learn that, and much depends on the contours of any eventual peace deal). Certainly, it’s worth saying that while FDR was much more interested in repayment than is remembered these days, Lend-Lease was nonetheless extraordinarily generous—far more than the support America has provided to Ukraine.

Still, this whole episode is yet another reminder, if it were needed, that even in a world getting less enthusiastic about net zero, minerals still matter enormously. If the U.S. and other nations are going to deliver all the infrastructure we need in coming years for green technology or data centers for artificial intelligence, they will need enormous quantities of battery minerals, not to mention old-fashioned stuff like copper, iron, and sand too. They have to come from somewhere—be it Ukraine or Greenland or, for that matter, America itself.

Ed Conway is a columnist for The Times of London and the economics editor for Sky News. He is the author of Material World: A Substantial Story of Our Past and Future. This article was first published on Ed’s Substack, which you can subscribe to here.

The Free Press earns a commission from any purchases made through all book links in this article.

Once upon a time, honorable men went to the gulags for refusing to repeat the Kremlin’s lies; now an American president is telling them for free. In the latest episode of Breaking History, Eli Lake takes us back to the Cold War and President Reagan’s support of dissidents.