The Free Press

Some time ago, a writer named Nancy Crampton-Brophy wrote an essay titled “How to Murder Your Husband.”

Two years ago, she was sentenced to life in prison for, well, guess what.

It was the kind of story where the headlines—and punchlines—wrote themselves. But if, like me, you happen to be a crime novelist, the whole thing was less hilarious than infuriating. Way to fuel the stereotype of the homicidal maniac in writer’s clothing, lady. You just had to murder your husband, and now mine won’t stop looking at me suspiciously every time I pick up a kitchen knife.

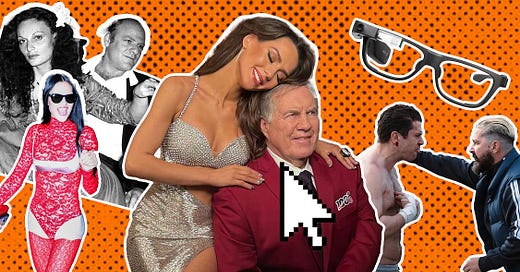

I wonder if any hip-hop artists have felt similarly since the security footage emerged last month of Diddy, né Sean Combs, assaulting his then-girlfriend Cassie Ventura at a hotel in 2016. The footage is shocking, and yet, in certain corners, it is being treated as inevitable. There’s a lot of shrugging and tsk-ing and “What did you expect from the guy responsible for lines like Got Asian women that’ll change my linen after I done blazed and hit ’em.”

In March, when Ventura first came forward with her allegations of harassment and abuse, former Honey magazine editor-in-chief Amy DuBois Barnett wrote in the Los Angeles Times that such behavior was the oldest of old news in the hip-hop world—that as the music became suffused with themes of misogyny and degradation, “it became aspirational for men to be violent toward women.” On black news site The Hub, an op-ed notes that rap lyrics about rape and abuse have long been de rigueur, under a headline that asks: “Hip-Hop Is Predatory but Why Are We Shocked?”

It is a troubling feature of the discourse that when a creator commits a crime, the bright line between art and artists doesn’t just blur but disappears altogether. But as the investigation into Diddy has ramped up, it is increasingly vital that we preserve the ability to distinguish between cruel words and bad deeds. As with Crampton-Brophy’s paean to spouse-killing, the rapper’s misogynistic music may well have described his real impulses. Certainly, between Ventura’s testimony and that terrible video, there seems to be little question of his guilt. But it is on the basis of this latter evidence, and not his lyrics, that we ought to convict him—a principle to keep in mind as the trial moves from media to courtroom.

This is no mere hypothetical: in recent years, a new class of prosecutors has sought to erase the distinction between a rhyming couplet and a criminal confession. Consider the case of the rapper Young Thug, who is currently facing a series of racketeering charges for his alleged role in gang-related activities, and whose rap lyrics have been repeatedly presented as evidence of wrongdoing. One representative song features Young Thug rapping, I shot at his mommy, now he no longer mention me—which prosecutors claim is a reference to an incident in which members of the YSL gang, allegedly led by Young Thug, fired on the home of a rival rapper’s mother.

What seems remarkable is that nobody has suggested that Young Thug committed this shooting himself, or even that he was present for it. The prosecution’s case rests on the notion that these lyrics are evidence not of Young Thug’s criminal acts, but his criminal mind; that a person who describes violence in song should be understood as the architect of that violence, instead of merely its documentarian.

To successfully convict an artist based on what he wrote or rhymed or painted—rather than what he did—is something of a Holy Grail for those who fear art as a medium for the spread of dangerous ideas. From the conservatives who denounce rap for promoting sexism and violence (while giving a pass to countless other genres, from country music to opera, which contain similar themes), to the progressives who demand that fiction conform to identitarian mores and seek to trash the perfectly good art of our problematic faves, authoritarian types have never liked the freedoms our country affords creators—especially the ones who seek to offend, to titillate, to challenge the pious and disturb the peace.

These censorious aspirations were an animating feature of certain parts of the Satanic Panic as well as the 1985 congressional hearings about the corrupting influence of rock music on America’s youth. They are also behind the repeated attempts by authorities to blame artists for crimes to which they have little to no connection, save possibly as background music. In 1997 and 2000, respectively, Marilyn Manson and Blink-182 were accused of writing songs that inspired listeners to commit suicide. In 1992, Tupac Shakur was sued by the widow of a slain police officer for inciting “imminent lawless action” after a cassette tape of his album 2Pacalyspe Now was recovered from the killer’s car.

Rap is, of course, one of few worlds in which being a convicted felon helps rather than harms your credibility. It’s easy to see how the music—with its peculiar honor culture and antiauthoritarian spirit—could tempt prosecutors to treat incriminating lyrics as evidence of a smoking gun. But for every defiant criminal in the genre, there are countless musicians who rap liberally about violent acts they categorically haven’t committed and who explicitly reject the idea that to be a gangsta rapper, you have to be both rapper and gangster. This latter group includes Ice-T, who wrote the song “Cop Killer,” which was censored in 1992, and who has killed exactly zero people, police or otherwise: “If you believe that I’m a cop killer,” he said at the time, “you believe David Bowie is an astronaut.”

Fani Willis, the prosecutor on Young Thug’s case (yes, the Fani Willis who investigated Trump), responded exasperatedly to questions about whether introducing his lyrics in court was a violation of the accused’s First Amendment rights: “I have some legal advice: don’t confess to crime on rap lyrics if you do not want them used.”

But what is a confession in this context? Countless songs describe such criminal acts: Eric Clapton’s “I Shot the Sheriff,” or my personal favorite, the Dixie Chicks’ “Goodbye Earl” (which includes the lyric, Ain’t it dark wrapped up in that tarp, Earl?): without a body, what are these evidence of? Johnny Cash did not, in fact, shoot a man in Reno just to watch him die. Alice Cooper, when he’s not crooning power ballads about the joys of necrophilia, is actually a down-to-earth family man and grandfather of four who volunteers at soup kitchens in his spare time. And no, #NotAllMurderFictionWriters are plotting to murder their actual spouses in their actual sleep.

The notion that there is no difference between words and violence may seem like a quirk of our current moment in history. But it’s always been an intoxicating idea. “Watch your thoughts, they become your words; watch your words, they become your actions,” said Lao Tzu, sometime before the birth of Christ. If you believe this, perhaps you also believe that the best way to stop bad actions is to seize hold of them when they’re still in their infancy, still trapped in the realm of thought—or fiction. It’s strangely comforting, when so much violence is random and senseless, to believe that there are warning signs everywhere: imagine if stopping evil were as simple as finding and silencing the guy who’s singing about it, painting it, telling stories.

But this is a delusion, one belied by the fact that our worst monsters rarely advertise themselves as such; at least as often, it’s the opposite. Bill Cosby, with his America’s Dad persona and goofy-looking sweaters, was responsible for far more material harm over the course of his life than every violent rap lyric stacked end to end.

Does evil hide in plain sight? Perhaps sometimes. Mostly, though, it just hides, and we can only imagine where and how. But the people who would collapse the distinction between artist and art, or art and artist, seem to put little stock in imagination. Indeed, the most extreme rhetoric from these corners would eliminate fiction as a category entirely—and with it, the ancient catharsis that comes from giving voice to the darkness that lurks in human hearts.

In this sense, rap is nothing new; some of the oldest known folk songs are murder ballads, which describe the most senseless and terrible crimes in the most graphic detail. Wives kill their husbands; young men kill their lovers; a woman and her child are murdered by a man named Long Lankin in a tune with the chilling lyrics:

He took out a pen-knife, baith pointed and sharp,

And he stabbed the babie three times in the heart.

These lines may well describe a real killing, just as Diddy’s lyrics may describe real violence—but it is the acts we must prosecute, not the words. To do otherwise threatens not just the freedom of artists to create without fear, but our ability as a society to reckon with the existence of the things that terrify us. In songs and in stories, we confront the human capacity for evil: staring it in the face, calling it by its name.

Kat Rosenfield is a novelist, writer, and co-host of the Feminine Chaos podcast. Read her recent piece for The Free Press, “Harrison Butker Is Catholic. So What?” Follow her on X @katrosenfield.

For more smart takes on the culture, become a Free Press subscriber today:

The traditional ballads of the Atlantic Isles are littered with violence.

In the Cruel Mother (Greenwood Sidee), the mother kills her newborn twins with a penknife.

But the difference is that she suffers the repercussions and the act is not glorified.

"Seven years in the flames of hell"

Kat, they’re not prosecuting words. They are prosecuting actions that were immortalized in song lyrics