The Free Press

We were in Europe in December 2021 when my twin brother—who had been backpacking on $100 a week and refused to waste a single euro on fondue or hot chocolate—told me he was going to buy a $3,000 camera.

Jackson, who had never voiced any interest in photography or filmmaking, said he wanted to become a videographer, to share his travels with the world.

I told him he was crazy.

Jackson had graduated in May from Drake University in Iowa, where he’d played soccer and studied computer science. I had caught up with him several months later after finishing my last classes at Stanford. We first met up in Paris, and he was wearing his single pair of sweatpants and parka he picked up in Finland, where he’d been chasing auroras.

I was born four minutes before Jackson, and I never let him (or anyone else) forget it. He was the athlete, and I was the cook. But together, we argued. For hours we argued about that camera. I suggested we hold a friendly competition between twins—who could make the better iPhone videos while in Europe? Creativity first; expensive camera later.

I didn’t see it at the time, but wanting an expensive camera was Jackson’s way of trying to commit himself to something he saw as big and real. This was bigger than competing with me, his brother. It was about his future.

The only thing I could think was that he was being stupid, and that this would be a stupid purchase—the cost equivalent of 30 weeks of backpacking around Europe blown on something he’d never previously dabbled in.

I was wrong. And it took me the better part of a year to figure that out. By then, everything had been turned upside down, and it would be my turn to do something rash and desperate.

Not long after Jackson’s declaration, we flew home to Iowa.

On New Year's Eve, I drove down to Texas to start a new job.

In February 2022, Jackson bought his camera. And returned it a few weeks later. He realized that, more important to him than any gadget, was getting out there—adventuring. That was confirmation, in my eyes, I’d been right.

In May, he visited California with me. I had to defend my thesis on campus before graduating. Jackson got in the night before I did and found the worst motel closest to the airport. When I told him he had to wear something “nice-ish” to an event, he went to a Gap, bought a sweater, and kept the receipt. He met my best friends and saw where I had spent the first years we had ever lived apart. Where he really wanted to be was back in Europe hiking and climbing. He left in July on a one-way ticket.

On August 15, 2022—a year ago this month—I was visiting my mother in Iowa City. I was still sleeping, just before 7 a.m., when she screamed my name: Maxwell! I ran down the stairs in my underwear and put her phone to my ear. She had already run out the front door.

On the phone was a consular officer at the United States Embassy in Bern, the Swiss capital. Jackson, she told me, had fallen to his death in a climbing accident near Zermatt.

“We’re very sorry for your loss, Mr. Meyer,” she said. “When you can, please call us back at this number. We have paperwork and need you to send us Jackson’s dental records.”

I don’t remember exactly how I spent that week. There were a lot of phone calls and walks. I know I fended off an armada of casseroles.

One thing I have solid evidence for is that on August 18, three days after learning of Jackson’s death, I emailed a broker inquiring about a 25-acre plot of land for sale. I had seen it online.

The next day, I walked those hills. The hills seemed never to end—I’d walk up one and see another. The grass was lush, the trees sparkling with light in the sunset. A white Mennonite church was perched on a nearby hill.

As I walked back to my car, the sun dipped below the horizon, and summer storm clouds rolled across the sky. Thunder began, then rain. But when I made it off the winding country roads back to the highway, the sky opened up, and a double rainbow beamed down on the wet cornfields. Whether I cried because of Jackson, or just because of the hills or the church or the rainbows, I don’t know.

When I walked in the door an hour later, I told Mom we had to call the bank.

It didn’t seem like the right moment for this kind of thing: friends were visiting Mom to grieve for my brother. Jackson was still lying in a funeral home in Basel, waiting for his final journey home on a plane to Chicago.

And I was in a rush to lock down my mortgage.

But Mom believed me when I said that I was sure I had to do this. To say that I had a plan would be an overstatement. But I had a feeling and a dream.

I bought the farm.

If Jackson and I learned the art of the stupid purchase from anyone, it was from our father, Bruce.

His mother had drowned when he was 17, and he was estranged from his father. He enlisted in the Air Force that same year, and was stationed in California, Iowa, and Georgia.

In the early eighties, he and Mom met at Missouri Western State University. They dated intermittently for years. In 1995, they got married.

They had four kids: my older sister, me and Jackson, and my younger brother.

In 2004, Dad retired from the service.

The year 2005 marked the arrival of Blocky—the first big stupid purchase. We needed a car—Mom was teaching high school math full-time, and Dad had to drop off and pick up the kids from school—but they didn’t have any money. One of Mom’s teacher friends offered us his 1990 Buick Regal for free. Dad insisted on paying $200.

He covered the Buick with colorful contact paper so that it looked like it was made of Legos. Then, we went to McDonald’s, bought lots of Happy Meals, and we nailed the toys in the Happy Meal boxes onto the top of the roof of the car. It drove Mom crazy. It was ridiculous. We called it Blocky.

Like Jackson’s camera, Blocky was a declaration of sorts—an insistence on laughing, smiling, and being silly in the face of turmoil.

By 2009, my father’s alcoholism had progressed to the point that he and my mother agreed he had to leave.

My mother suggested he do the thing he’d talked about for ages—go work on a boat. For a month, he joined a fishing ship in the Atlantic off Virginia as a crew member.

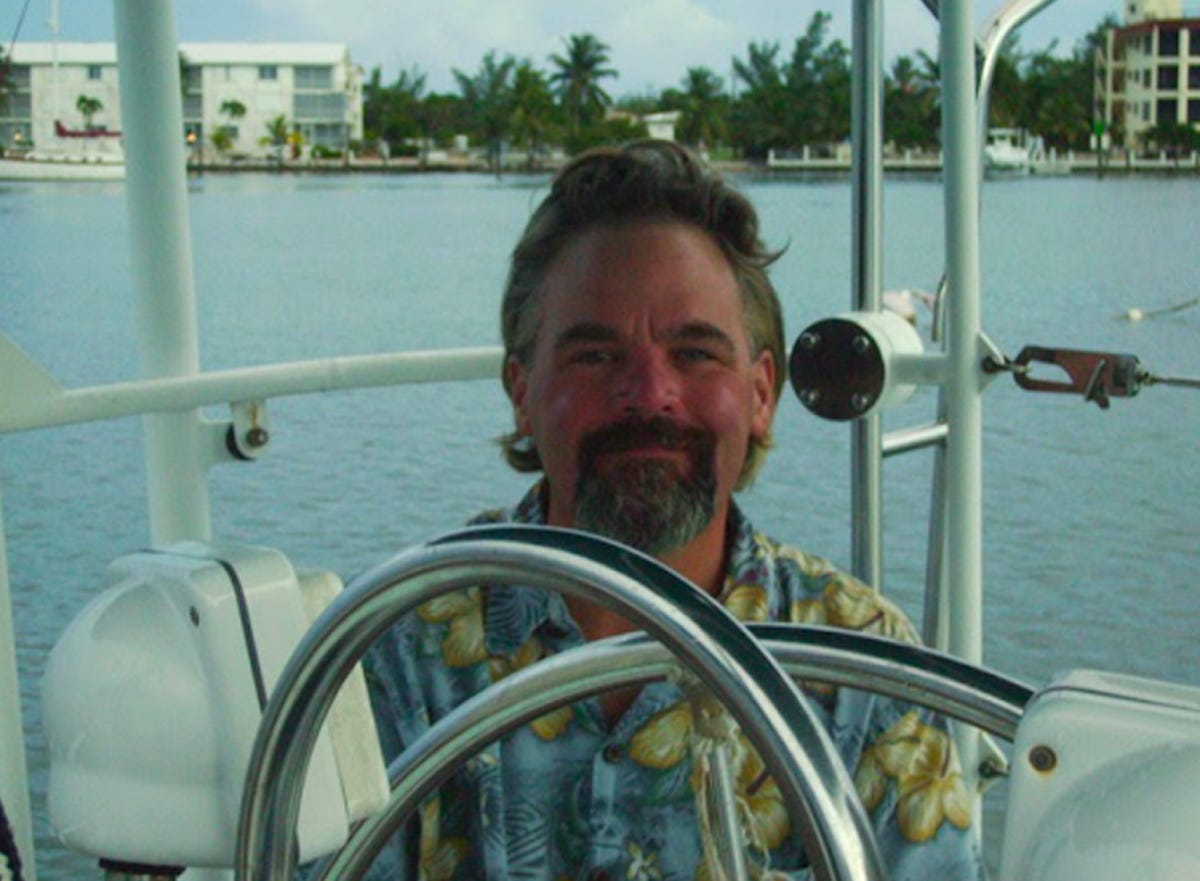

But Dad wanted to be his own captain. So, he liquidated his 401(k) account, about $50,000, and bought a large sailboat—the second and much stupider stupid purchase. My mother was stuck with the tax bill.

For a year, Dad lived on that boat, the Remajale, out of Marathon Key, Florida. He loved it. He even found a crew.

But the crew abandoned ship when they grew distrustful of their captain. The last straw was when he refused to tell them what Remajale meant. It was a secret he didn’t want anyone in that new world to know, a reminder of the world he had had to leave—a portmanteau of the names of his four children in the order they had been born.

I’ll let you in on the secret: Rebecca, Maxwell, Jackson, Lewis. Remajale.

After a year, Dad ran out of money and had to return to the mainland. He left the Remajale in Florida. After a few years of paying to store the boat—for $500 a month—he gave it to charity.

Mom would later describe that time as a state of financial wreckage that we kids would never fully understand. She’d spent her savings paying his taxes, and without him to look after us, she could only work part-time. She had sacrificed everything, and she had been deprived of the opportunity to make any purchases of her own, stupid or otherwise. Because my father had been too stupid for both of them. Financial aid and military charities paid for Stanford. Jackson got soccer scholarships at Drake.

My father had been lost in the woods and trying to find his way out. And on that boat, he was happy. On it, he tried to become the person he’d always wanted to be.

In May 2014, he lost that battle. He was 53 when he took his own life.

There’s one stupid purchase Dad never made.

A year before his suicide, he took me out to the countryside. Somewhere in Iowa. He said he was thinking about buying some land. He’d use it as a place to hunt, and to ride out the national anarchy he assumed would soon be upon us. I know now that he didn’t have any money to buy it, but he was set on me coming to visit the plot with him. I don’t know exactly what his game was. If he was trying to plant an idea in my head, it worked.

In October 2022, I closed on my property, which cost a little more than $200,000. I was a landowner at the age of 22, made possible by a mortgage and years of saving.

In June, the builders finished constructing a 384-square-foot cabin, which had been designed by an outfit in Vermont I visited with friends.

I planted grapevines, plum trees, and blueberry bushes, and my neighbor, who is a farmer, helped me cut and bale hay, which I gave to him for the trouble. (He has cows.)

It was only then, when I was surveying my hay, the fields, the cabin, that I could see my purchase in all its glorious stupidity.

Obviously, I hope this purchase is a success—I don’t expect I’ll be forced to sell; I don’t think it’s going to ruin me. It was more the rashness of it all.

Really, it was the need to do this, to declare in the clearest, most unequivocal way possible that this was the future I craved.

I know now that stupid purchases are a privilege—no, a miracle. I know that behind every stupid purchase is a human being trying and maybe failing to find his way, to declare his values to a world that doesn’t always listen.

Recently, I invited several old friends from my summer camp days to stay with me on the farm for a few nights. We walked the hills at dusk. We sat around a fire. We drank bourbon. We sang songs. We slept in tents on the field outside the cabin, and when we woke up in the morning there were birds and a fiery sun.

I think Dad would be proud and jealous. Jackson would say I’m an idiot, tackle me, and then ask where I’m putting the shooting range. I hope he would approve of the name I’ve given my property: Henry Hills. Henry was his middle name.

One day, I will build a real memorial on this land for my brother, and I’ll place the old wooden bench Dad bought ages ago on one of the hills—a place for sitting with a friend, like I used to do with him, but can’t anymore.

In this place, I’m going to build my own world, a world big enough for all my memories. When people ask about it, I’ll tell the story of how I learned that dreams shouldn’t wait. That there is never as much time as we think. That sometimes making a stupid purchase is the only thing that makes any sense.

Max Meyer works at the venture capital firm 8VC in Austin, Texas. Follow him on Twitter @mualphaxi. And read his last Free Press piece about the MAGA Hamptons here.

To support our mission of independent journalism, become a subscriber today:

Also: We’re hosting our first live debate on September 13 at the Ace Theatre in Los Angeles. Has the sexual revolution failed? Come argue about it and have a drink. We can’t wait to meet you in person. You can purchase tickets now at thefp.com/debates.

In a world that is increasingly fake, we hold onto things that are real, and land is real. Good for you for buying. Bold, but not stupid.

That was lovely