The Free Press

Every few years, the algorithm latches on to a new justification for doing absolutely nothing.

Sometime this winter, I noticed videos about bed rot, which is what it sounds like: plonking down in bed indefinitely. Like most people, I didn’t need an instructional video to teach me about lying down. My bedroom is tiny; it basically just fits a bed, on purpose. I’m one of those people guilty of working, watching TV, and in rare, particularly undignified moments, eating in bed. I’m not proud. I certainly didn’t know there was a name for this slovenly behavior.

Then, more recently, the term hurkle-durkle began flashing across my screen. This one sounds more like you’re having a stroke in a fairy tale, but the message is the same.

Videos on TikTok are quick to explain that hurkle-durkle is an eighteenth-century Scottish concept, wherein you stay in bed past the time you’re supposed to be up. It comes from the words hurkill, meaning to crouch, and hurklin, meaning to stagger. But on TikTok and Instagram it means to hit snooze, curl up under your duvet, and relax. To hurkle-durkle is to be at rest but not exactly sleeping. Kind of like you’re in a coma.

This is not the first time a European concept loosely tied to hanging out has captured hearts online. There was hygge, from Norway, which means getting cozy inside the house—presumably by a fire, during long Norwegian winters. Fredagsmys is the Swedish word for staying in on a Friday.

These have dovetailed with various de-productivity trends that don’t have a Scandinavian patina but mushroom up nonetheless, like quiet quitting, which is about keeping a job but purposely not excelling at it, and the soft life, which instructs us to choose comfort and ease over the hustle and grind of getting up and squeezing the most productivity possible out of the day. There is endless content about the sweet relief of canceling plans, and nostalgia for the pandemic lockdowns, where not having plans became something of a moral win.

File all of these online trends under the large umbrella of self-care, which has become shorthand for just doing whatever you want to. Taking care of your skin? Self-care. Cooking while sad? Self-care. Protesting? Self-care. Taking a dance fitness class? Self-care. Lying in bed all day? Also self-care.

Self-care is like self-help, but with no goals or striving. The $11 billion industry is mostly geared toward women, and while hurkle-durkle might not be associated with a particular product, it smuggles in the same insidious message: anything you do for yourself is inherently good and you should never feel guilty about it.

That’s how being idle has become synonymous with being well. It’s how being chronically ill has become a sacred identity. It’s how, if you signal your beliefs zealously enough, sleep can even be activism, and your bed can be ground zero for a revolution.

Except not.

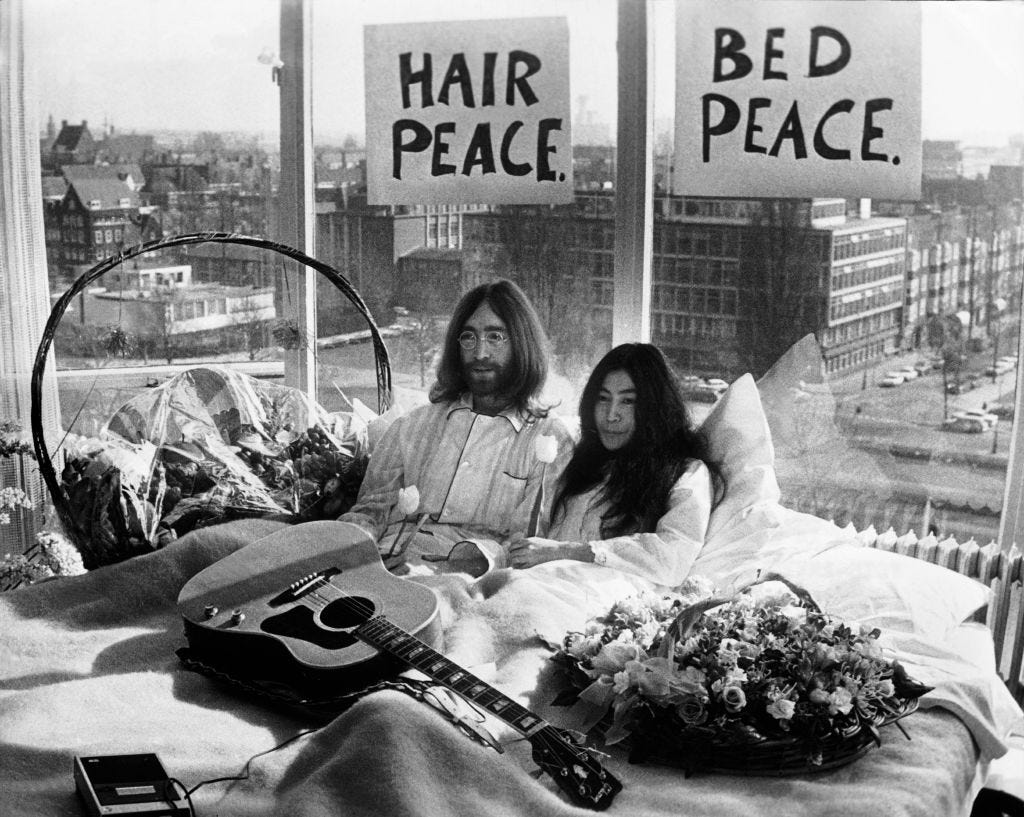

The Vietnam War didn’t end after John Lennon and Yoko Ono spent days doing “bed-ins” in hotels in Amsterdam and Montreal in 1969, and even they admitted the demonstration was kind of a joke. As a bed-rotter by nature, I wish staying in bed could bring about progress, but all of human history begs to differ.

Of course, there is no shame, if you’re sick or grieving or newly married or heartbroken, in spending a little extra time under the covers. There is a difference between being a bed person and being a hermit.

So many stories covering the hurkle-durkle trend ask whether it’s possible to stay in bed for too long, invariably asking the experts to weigh in, as if you need a sleep specialist, a kinesiologist, and a psychiatrist to spell out what is painfully obvious: making a hobby out of being horizontal is a very bad idea. Hurkle-durkle posts always glamorize it—the videos show women in cloudlike queen beds, with a candle burning, possibly an open book. But should we glamorize solitude?

When I see videos of women luxuriating in their bedroom during daylight hours, I don’t think of Scottish people cozying up with a quilt and a book of poems. I think of Japan, and the legions of social hermits called hikikomori. There are an estimated 1.5 million hikikomori, or “shut-ins,” according to the Japanese government. While they’re mostly men, the hikikomori take hurkle-durkling to the extreme: to qualify as one, you must stay in your home for six months or longer, sometimes in the same room.

We’ve become like the hikikomori here in America—it’s only that we call it hurkle-durkle and self-care and bed rot.

It’s not just that people are giving in to being alone and calling it liberation. It’s that those people who are striving, who are working hard, who are willing to fail and sweat, are demonized as try-hards.

Trying hard is good. Those who resist bed rot—which include both tradwives and girlbosses, by the way, and yes, I know whatever readers I had holding on until now I’ve now lost—know that their time is limited. They know we’ll all be hurkle-durkling forever, in the cold, hard ground. So they choose not to sedate themselves. We’d all be wise to choose the same.

Suzy Weiss is a reporter at The Free Press. Follow her on X @SnoozyWeiss.

For more on internet culture (and a lot more), subscribe to The Free Press:

Ok, we have a tonic for this one. Every morning, greet the SUN, look around your home or property and decide that today you will accomplish one task. It turns out that accomplishing something feeds our brain reward system. This article from the NLM (National Library of Medicine) can get you started on getting out of bed and doing tasks throughout your life as Humans are meant to do. "The mesolimbic system, also known as the reward system, is composed of brain structures that are responsible for mediating the physiological and cognitive processing of reward. Reward is a natural process during which the brain associates diverse stimuli (substances, situations, events, or activities) with a positive or desirable outcome. This results in adjustments of an individual’s behavior, ultimately leading them to search for that particular positive stimulus. Reward requires the coordinated release of heterogenous neurotransmitters. However, of the brain substrates implicated in reward, dopamine has a central position. Dopamine plays a critical role in mediating the reward value of food, drink, sex, social interaction, and substance abuse (Hernandez and Hoebel 1988; Everitt 1990; Robbins and Everitt 1996; Bardo 1998; Beninger and Miller 1998)." https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8992377/#:~:text=Reward%20is%20a%20natural%20process,for%20that%20particular%20positive%20stimulus.

Go outside if you have a yard and with pruners in hand chop off that out of control branch of vine. Cutting something other than oneself can bring great satisfaction. It may even cause you to sweep the walk (I remember sweeping our walk as a child and wanting that to be my job as part of our family). Inside the house, notice that ball of fur lodged in the corner or under the stools at the kitchen counter. Pick it up and before disposing it, think of where it came from. In our case, its a result of having four pups that all shed fur or hair that ends up accumulating in out of the way places like those I mentioned as well as behind doors and of all places on top of door hinges. When you pick it up, notice how soft it is or if it contains long strands of human hair as well. Think about how it could be woven into thread like wool from a llama or sheep. Or my best thought of how to reuse it by placing it on a branch for a nesting bird to add to the nest. Let's get back to being Human and search for that particular positive stimuli, and get those doses of dopamine from our natural acts of reward rather than scrolling for hours to watch photos or videos of messy and sometimes disgusting hurkle-durkle bed-head's bedroom set up.

Maybe. No one is working on identifying whatever it is, of course—unless they're in some secret laboratory under a mountain in Appalachia. We did get the first two shots, which we now regret. And of course got Covid too.