The Free Press

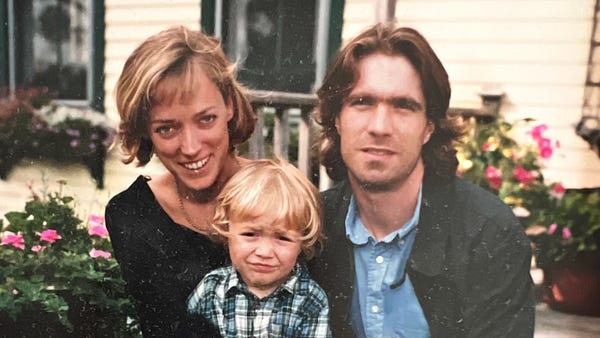

My eldest brother, Samir al Mutar, was born in August 1980. He was a talented computer engineer who led a company that, to this day, installs and builds internet databases across Iraq.

One day in November 2007, on his way to work with a couple of his friends, he was stopped at an al-Qaeda checkpoint. His friends fled. My brother was never seen again.

That day was the first time I had ever seen my dad cry. I will never forget the sleepless nights that followed, listening to my mom’s sobs while I tried to study for my final high school exams. I knew then that I needed to finish school so that I could one day build a life far away from the danger.

My parents tried everything possible to reach my brother or even meet with his kidnappers. After weeks of trying, the U.S. military showed them a picture of my brother that confirmed he had been killed. We still don’t know exactly what happened to him, and we have never been able to recover his body.

By the time Samir disappeared, I’d become desensitized to death. The war had been raging for four years, and the civil war triggered by the war (and, more proximally, the destruction of a Shia mosque) had been going on for a year. I was used to seeing dead bodies tossed in the street mere feet from where the school taxi picked me up. Many days, I had to step over corpses on my way to school in the Al Khadra district.

So when I heard about my brother, I could barely express any emotion. This still haunts me.

My brother’s murder led me to start fighting against al-Qaeda in West Baghdad—as much as a 15-year-old could. Sunnis, in close conjunction with U.S. forces, had organized a small army called Awakening Forces, and a friend recruited me. They gave me a cell phone, which I used to send coordinates of al-Qaeda forces to our commanders. I was part of a larger operation to rout al-Qaeda from the city. We succeeded.

But that made me a collaborator in the eyes of al-Qaeda, and there was a target on my back now. Two years later, in 2009, when the U.S. started withdrawing from Iraq, al-Qaeda began picking us off one by one. The day I received a letter containing a bullet I knew I had to flee.

Soon after, my brothers managed to get to the United States. I escaped to Lebanon, and from there, I made it to Malaysia, where I applied for refugee status. In 2013, I finally arrived in America. Today, my family is spread across the United States and the UK.

For all that, for all the chaos, for all the dislocation, for the grief that will never leave me, I don’t harbor any ill will toward America. I don’t share the conventional wisdom that the U.S. invasion—this week marks two decades since American forces poured into Iraq—was a colossal failure. I believe that the invasion was the necessary beginning of a long, tortuous and still uncertain road out of a very dark past.

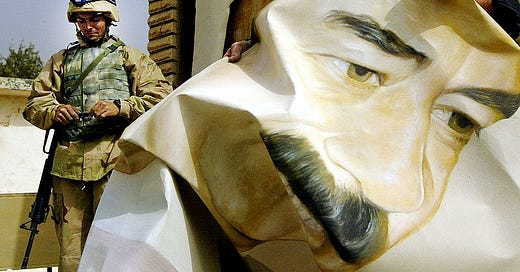

On April 2, 2003, I was at home, in a middle-class neighborhood of West Baghdad, when the Americans arrived. Samir, the oldest of our family’s five siblings, called for us to watch the tanks descending on the city, rolling past our kitchen window.

We were surprised to see the Americans: Iraqi state media had been telling us the Western imperialists were being crushed in the south.

In the opening days of the war, the Iraqi Army had turned my elementary school, a block from our home, into a makeshift military base. The Americans bombed the hell out of it, and our house shook every time a rocket detonated.

Iraqi soldiers often ran to our home for safety from incoming fire. I recall my brother’s friend, Hassanian, who was in the army, showing up at our front door to tell us that the Iraqis were being routed and that the war would end soon. That was the first hint that what we were being told on television was a lie.

Then again, our reality was strange.

One moment, I saw our neighbor Hisham outside our house carrying flowers to American soldiers, and the next, I was staring at a severed limb in our backyard that was thought to have belonged to an Iraqi soldier.

Underlying our fear and uncertainty was a hint of optimism. We thought that, if the Americans destroyed Saddam Hussein’s regime, we might have a better life.

I had been thirsting for freedom as early as elementary school. My headmaster was an outspoken Ba’athist, and my dad, an underpaid orthopedic surgeon who had been trained in England, would warn me not to repeat anything we spoke of in our home—the horrors perpetrated by the regime, and my dad’s hopes that one day Iraq would embrace Enlightenment values.

The two of us would listen to Radio Sawa, which is broadcast across the Middle East and funded by the United States, under cover of nightfall. Our family friends had satellite television, and similarly had to hide the receiver. If anyone was caught with unapproved radio or television devices, their arrest was almost inevitable. It was like this pressure always bearing down.

This was the same regime that had invaded Kuwait, in 1990, to acquire oil reserves and nullify its debt. The same regime that had actively supported terrorist groups and the families of suicide bombers in the Palestinian territories. (Say what you will about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Paying young people to blow themselves up was barbaric.)

Saddam was the symbol of an ideology that was hateful and warlike and opposed to any kind of self-government. His sons were known for picking out women at weddings, raping and killing them, and sending their corpses to their families—who would be killed if they complained.

These were the people who ruled over my family and 30 million other Iraqis.

After the Americans arrived, despite all the chaos, you could feel the pressure lifting. But it was not an easy time. Far from it. You could never be sure what was coming. And as the war stretched across the spring and summer of its first year, many people who used to live in my neighborhood started leaving, mostly for Jordan. Their once-occupied homes became vacant and quiet, with shrubbery growing over the doors.

We stayed. My dad didn’t want to go. He felt it was his duty, as an educated person, to help his country and his people.

Two decades after this event that put in motion the events that reshaped my life and the life of everyone I love—the U.S. invasion of Iraq—the conventional wisdom is that the invasion was an unmitigated failure. America spent nearly $2 trillion on the war—far more than the roughly $700 billion that is often reported and significantly more than the $50 billion to $60 billion the Bush Administration projected. The U.S. lost nearly 4,500 soldiers. Almost a half-million Iraqis were killed.

And for what? Today, Iraq is struggling to rebuild itself. Iran and ISIS remain a serious threat. The Americans hoped to build a Jeffersonian republic in the heart of the Middle East, and failed. The whole thing seems like a horrible, tragic mistake.

I disagree.

Maybe that sounds crazy to you. I lost my country. I lost my beloved brother. I lost friends and neighbors. My family was uprooted and is now separated by an ocean.

And yet.

It is hard to express what it means, if you have lived under an authoritarian regime, to experience freedom. Those who have grown up with the privilege of liberty are lucky not to understand it—and the heavy price you are willing to pay for it if you have lived without it.

But having the chance to elect your leaders is better than having zero say in who governs you for life.

Having the chance to speak freely—the barbarous casualty count notwithstanding—is better than being hunted down for the sin of wrongthink.

Having the chance to defend yourself, as the people of Kurdistan have shown—the seemingly insurmountable obstacles notwithstanding—is better than a people so utterly subjugated they lose the will to fight.

Having the chance to pursue an education to the fullest extent of one’s intellect—persistent gender inequality notwithstanding—is better than consigning an entire population to illiteracy of anything beyond the books dictated by the regime.

Having the chance to make others laugh—potential persecution for doing so notwithstanding—is better than a life entirely devoid of humor.

Something I learned from my dad early on is that no regime can take that away from you—that questioning of official truths, that ability to think critically.

This is why, despite everything, despite all of the experts and the conventional wisdom and the unpopularity of my views, I remain optimistic that one day, I will be able to travel back to my old neighborhood. To go back to my old home. To revel in the memories I shared with my family there. Especially with Samir.

For further reading about the 20th anniversary of the war in Iraq. . .

When you get 20 minutes, check out this op-doc from the New York Times featuring veterans of the war: Iraq Veterans, 20 Years Later: ‘I Don’t Know How to Explain the War to Myself’

For an enormously powerful firsthand account, read this essay by Will Selber, who spent 1,500 days downrange in Iraq and Afghanistan: Moral Injuries

Some startling images: The Start of the Iraq War 20 Years Later in Photos

If you’ve never read Dexter Filkins’s book, The Forever War, we highly recommend it. (Start by reading an excerpt here.)

Finally, the latest episode of Honestly, with war reporter and author Sebastian Junger, is about why men seek danger—and perhaps even need war. If you haven’t listened, it’s one of our favorites so far:

If you believe in the work of The Free Press, subscribe now:

The Free Press earns a commission from any purchases made through Bookshop.org links in this article.

Some number of years ago, I read the comments of an Iraqi girl about the US invasion. She had a negative view of the invasion, but not for the reasons most Americans might guess. Given, that she was living in the US, she was hardly anti-American or pro-Saddam.

In her personal experience, the US invasion brought chaos to Iraq. Before the invasion, water and electric power worked. After the invasion, not so much. Before the invasion, she could safely go outside. After, the invasion, people hid in their homes. She was hardly naïve about Saddam’s regime. According to her, parents of the kids she went to high school with would disappear from time-to-time. She had a clear idea of what happened to them.

In her view, order was better than chaos. Her views shocked her ‘born in America’ classmates who more or less universally expressed a preference for chaos. She knew better. Chaos only seems romantic to those who don’t have to endure it.

Thanks for the praise of the advantages provided by the American system. But I'd grant more credibility to the opinions about the Iraq invasion expressed in the article if they had been written by someone still living in Iraq.