The Free Press

“Grotesque.”

That’s what Lord Jonathan Sumption thinks about Hong Kong’s abuse of the law—and how it’s silencing anyone opposed to the Chinese Communist Party.

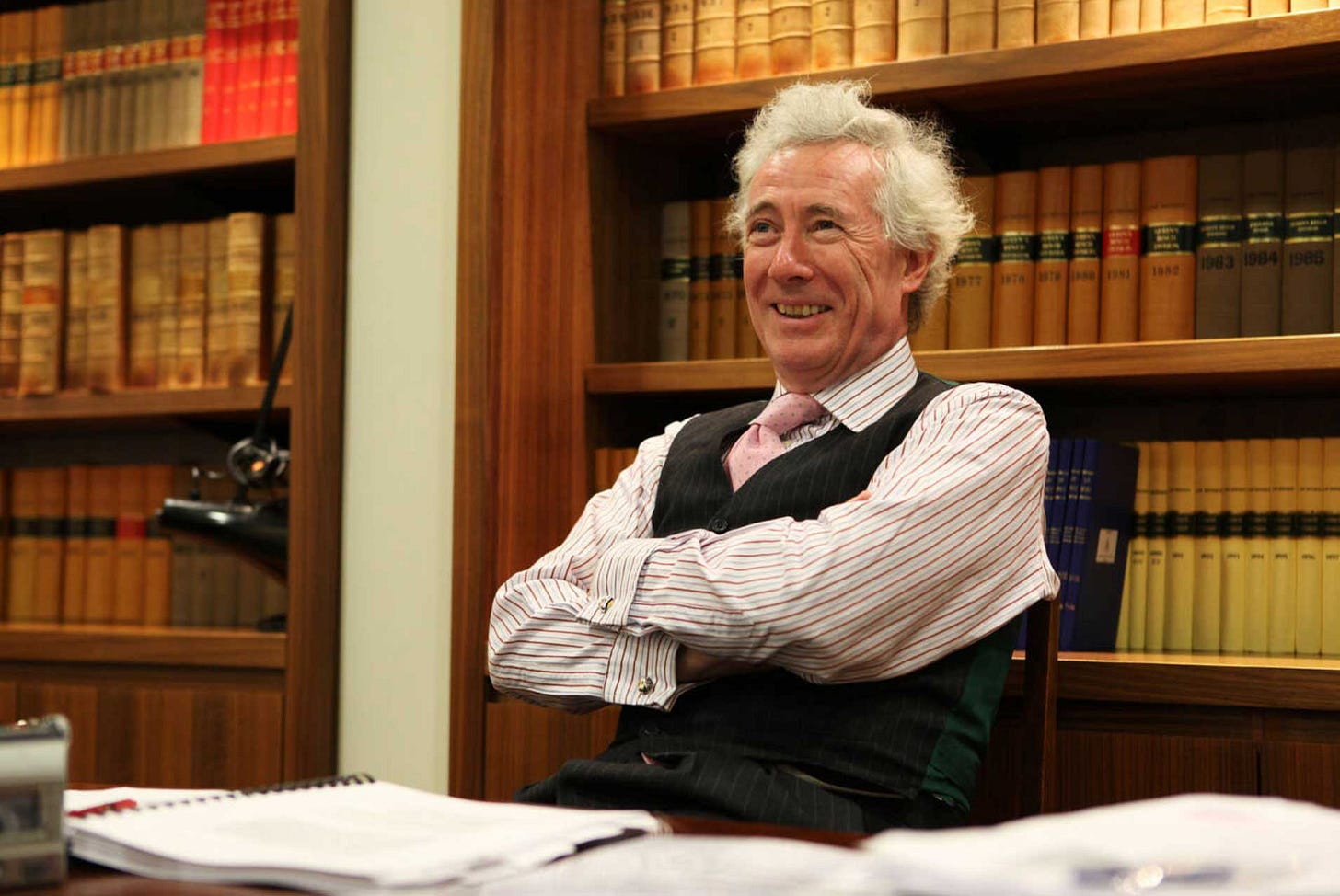

A former member of the United Kingdom’s Supreme Court, Sumption became a “nonpermanent judge” on Hong Kong’s Court of Final Appeal in December 2019.

But Sumption isn’t just any judge. He’s a famed medieval historian, and he is widely agreed to be among the best lawyers of his generation. An article in The Guardian almost a decade ago referred to him as “the brain of Britain.” He has also built a career as an independent-minded, free thinker—one who railed against Covid lockdowns and affirmative action-type quotas, but who has also fiercely criticized Israel’s conduct in Gaza. Sumption, to put it simply, is nearly impossible to define into neat partisan labels.

His role in Hong Kong was to sit on a few cases on the territory’s highest court each month to ensure they complied with the country’s Basic Law and other statutes. He told me he thought he would have a positive impact on the legal system in the territory, which used to be a British colony until it was handed back to China in 1997.

But last year, he witnessed a situation “so unattractive” he didn’t “want to be part of it anymore.”

The “turning point” for him was the prosecution of 47 people on political grounds. Known as the “Hong Kong 47,” the group of activists was first charged in 2021 for conspiracy to commit “subversion” after holding a primary election that would boost pro-democracy candidates—an act Sumption calls their “constitutional right.”

And yet, last May, 31 pleaded guilty, and 14 of the 16 who stood trial were convicted. Those 45 were sentenced to prison, with terms ranging from four to 10 years. It’s “a legally indefensible position,” said Sumption, driven by “fear of the pressure of China.”

That’s when Sumption had a realization: He had become part of China’s mission to squash dissent. Even though he did not take part in the rulings against the 47, in June 2024 he resigned from his post on Hong Kong’s highest court, along with another British judge, Lord Lawrence Collins.

In an op-ed published shortly after his departure, Sumption wrote that Hong Kong was “slowly becoming a totalitarian state.”

“All that we were doing was giving a spurious impression of legitimacy to a system that was becoming increasingly unattractive,” he told me.

This month, Sumption published a book, The Challenges of Democracy: And The Rule of Law, which, in part, explores Hong Kong’s spiral toward authoritarianism. He told me he’s “not optimistic” that the rule of law will ever prevail under China’s grip.

“I think that Hong Kong will gradually become more and more like China. The best is no change, and the worst is a growing totalitarian model.”

Today, there are six foreign judges—two Brits and four Australians—still serving on the Court of Final Appeal. They are all men over the age of 70 who held prestigious judicial posts in their home countries before they were invited to serve on the court by Hong Kong’s chief executive.

Their work as “nonpermanent judges” may seem unusual, given that none of them are from the city. But their role is actually written into Hong Kong’s Basic Law, which says the court can “invite judges from other common law jurisdictions to sit on the Court of Final Appeal." The court has “the power of final adjudication.”

“It was kind of a vestige of the colonial system,” said Alyssa Fong, the advocacy manager for The Committee for Freedom in Hong Kong Foundation, of the foreign judges serving on the region’s court. The belief was that “it could only be good” to have “internationally recognized and highly reputable judges sitting on those courts and helping out Hong Kong judges,” especially with complex cases.

The Basic Law, written in 1989 and agreed to by the Chinese government in 1990 to prepare for the 1997 handover, was meant to ensure Hong Kong residents would continue to enjoy the same rights they did under British rule—rights like freedom of speech, freedom of religion, the right to privacy, and equal protection under the law. In China, this unique arrangement was referred to as “One Country, Two Systems,” or yīguó liǎngzhì (一国两制).

But, Sumption told me, “The Basic Law confers on the Chinese legislature in Beijing the right to ‘interpret.’ ” Or, in other words, “to remake the law in any way they like.”

In the wake of pro-democracy protests in 2019, Beijing imposed a National Security Law to crack down on dissent, which included arresting people for attending protests or even standing on the sidelines to film them. Last March, the law got an even harsher update—expanding the rights of police to restrict citizens’ access to bail and legal representation after arrest.

Today, there are over 1,900 political prisoners in the territory, according to the Hong Kong Democracy Council. The most famous is Jimmy Lai, the 77-year-old billionaire founder of pro-democracy news outlet Apple Daily. Since December 2020, he has been held in solitary confinement for conspiring to publish “seditious publications,” participating in pro-democracy protests, committing “fraud,” and hosting a vigil honoring victims of the 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre.

Lai’s trial for “conspiracy to collude with foreign forces” is currently ongoing, and has so far lasted more than 100 days. Lai’s son Sebastien told Reuters last week that his father is “breaking down” in prison and that his “time is running out.”

Meanwhile, Lord David Neuberger, the former president of the UK’s Supreme Court, was part of a panel that denied Lai and six other activists an appeal last summer. Ironically, Neuberger is a press-freedom advocate, who formerly served as chair of the Media Freedom Coalition’s High Level Panel of Legal Experts on Media Freedom. Neuberger had not responded to a Free Press request for comment.

Fong said Hong Kong is guilty of “weaponizing” its international judges, enabling the government to say it’s “still normal, still operating in the ways that it always has been.”

“Obviously, we know that’s not the case,” continued Fong, who took part in pro-democracy protests in 2019 when she was a college student studying psychology. Today, she believes Hong Kong is “the puppet of China.”

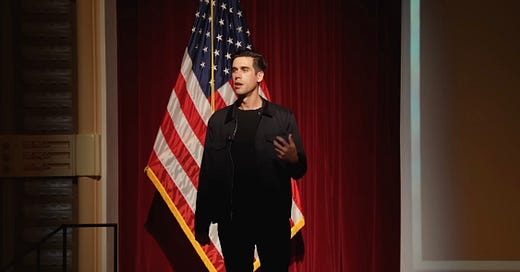

A handful of Americans have also been targets of Hong Kong’s National Security Law, including Joey Siu, who fled to the United States in 2020 out of fear of persecution. In December 2023, Hong Kong police put a $1 million bounty on her head for her activism, which includes working with the pro-democracy nonprofit Hong Kong Watch and giving testimony before the U.S. Congress in 2020 about human rights abuses in the city.

In December 2019, Samuel Bickett, a U.S. lawyer who worked for Bank of America in Hong Kong, also became a target. That was after he saw a man beating a woman with a baton after she jumped a subway turnstile, and he stepped in to help. Bickett ended up in a physical fight with the man, who turned out to be an off-duty police officer.

He told me his trial “was rigged from the beginning”—and that Hong Kong used the full force of the law against him because of his U.S. citizenship. (Just a few weeks before his arrest, Congress approved sanctions against Hong Kong officials for imposing the National Security Law.) While imprisoned alongside dozens of pro-democracy protesters in one of Hong Kong’s oldest jails, Bickett leaned on his legal knowledge to help them in their own cases, making him a prominent activist in his own right.

Ultimately, Bickett was convicted and sentenced to four months in a maximum security prison. He was released in March 2022, and deported back to the U.S.; he now lives in D.C.

Last May, Fong and Bickett co-authored a report arguing that “foreign judges are undermining Hong Kong’s freedoms.” They point to at least five cases in which foreign judges “have directly ruled against political defendants.”

One of those cases cites Sumption—who ruled in favor of a unanimous 2021 court decision allowing people to be charged with rioting even if they’re not physically present at a riot. “Lord Sumption’s name on the judgment helped give the government the credibility it needed to defend the crackdown,” the report states.

But Sumption told me he is “puzzled” by the criticism this decision received. He said it’s always been the law, both in Hong Kong and the UK, that people who “share the violent intentions” of a mob are “equally liable criminally for the offense of disorder.”

He also defended his service in Hong Kong, telling me he doesn’t “regret” staying on the court even after Beijing’s crackdown—and he doesn’t judge his colleagues who remain there today.

“I certainly felt, and I believe that probably most of my colleagues felt, one should hang on as long as possible as a civilizing influence—an element of restraint in a society which seemed to be heading in an undesirable direction,” he told me.

But Bickett isn’t buying that argument. “These people are infuriating to me,” he said of the judges. “You've got them going on and repeatedly saying: ‘We think that the rule of law still exists. We think the courts are trying as hard as they can.’ And they’re just completely dismissing the fact you’ve got political prisoners getting convicted of crimes where there is little or no evidence that they committed any crimes. And you’ve got people accused of crimes that aren’t crimes in any modern democracy.”

Sumption, on the other hand, said the judges who remain in Hong Kong are people “of massive personal integrity, and I wouldn’t dream of criticizing them simply because I have taken a different view.”

“It's a bit like the slowly boiled frog,” he added. “We jump out of the water at different stages.”

He also opposes the Hong Kong Sanctions Act, currently being debated in the U.S. Congress, which would impose further sanctions on any Hong Kong official—including judges—who persecute pro-democracy activists. He called the proposed legislation “grotesquely unfair.”

“It’s fashionable to criticize the judges in Hong Kong,” he told me, “but the judges are in an impossible position, and their difficult situation has been created by the People's Republic of China.”

“The real target,” he added, “is the Chinese government and to some extent the Hong Kong government, who have created this situation.”

But Fong is less forgiving. “If I had seen any shred of evidence that they were there to help, then I would absolutely say, ‘Yes, we need those voices who know about freedom of assembly and freedom of speech to stay in Hong Kong and to advocate for what we’ve always had,’ ” she told me. “But they’re not doing that. They’re actively destroying it alongside the Hong Kong judges.”

“They had the perfect opportunity, and they threw it away,” she added of the foreign judges. “So they should leave.”