The beginning of the end came in 2017.

After a New York Times report exposed the supposedly sexually charged “boys’ club” atmosphere at Vice—a magazine started by three boys in 1994—a clutch of employees publicly condemned their employer for its past and demanded that the company that paid their salaries start acting like an entirely different company.

Vice co-founder and CEO Shane Smith, once a frequent presence in the New York office, retreated to his $50 million L.A. mansion and transferred control of the company to a female CEO, former A&E Networks head Nancy Dubuc. A staff-wide email from Smith and fellow Vice co-founder Suroosh Alvi, sent hours before the Times story dropped, offered an expression of “extreme regret for our role in perpetuating sexism in the media industry and society in general,” which rather overestimated the company’s influence and overstated their sense of contrition.

After all, Vice’s top leadership, in private, was far less acquiescent, bitterly arguing that the Times story was a conclusion in search of supporting anecdotes, with complicating facts ignored to sustain a predetermined narrative. Regardless, profuse apologies were demanded and frequently repeated. But they weren’t enough.

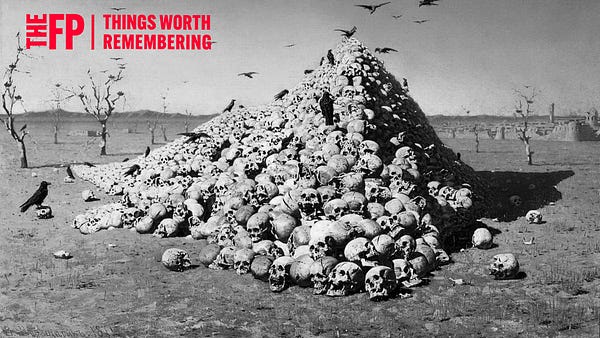

The walls of Vice’s sprawling Brooklyn headquarters were lined with magazine covers charting the company’s transformation from insouciant Canadian post-punk magazine to money-printing media colossus. In early 2018, long before college students discovered that dispatching problematic statues into canals would be reliably met with institutional approval, a group of employees demanded that the covers be removed from the walls.

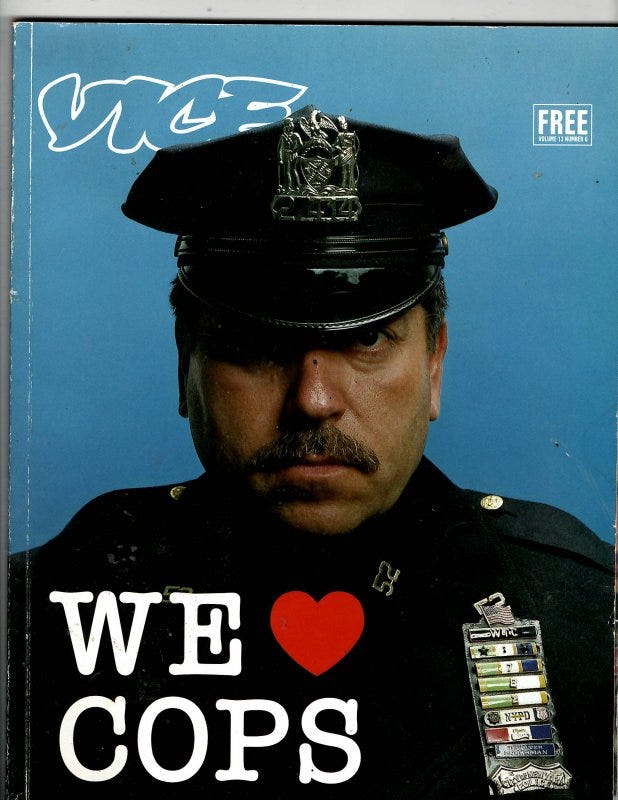

Not a specific cover. All of them.

The supposed offense varied by complainant. Some referenced covers shot by the recently defenestrated photographer Terry Richardson, an occasional Vice contributor accused of using his position to sexually harass his subjects. Or maybe it was the half-ironic “We Love Cops” cover, a sentiment inconceivable to a generation uncomfortable with both irony and the police. But likely it just was the general unease of working for a publication that once lived up to its name, proudly embracing sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll.

The covers were swiftly removed, now sequestered in co-founder Suroosh Alvi’s basement office, where a number of longtime Vice employees gathered to express a collective incredulity. “The resistance starts now,” one of them said hopefully. But we all saw it for what it was: a surrender.

It was the first in a cascading series of I told you so moments. In a building full of poorly paid, expensively educated young journalists, laboring on behalf of lavishly paid, expensively educated executives, it was inevitable, in an age of perpetual offense, that Vice Media would soon be consumed by controversies about its past, providing excuses to reshape its future. But if you’re endlessly apologizing for the very content that created all of these jobs, as I told one executive at the time, it will end up destroying the company.

While you couldn’t unpublish old issues of the magazine, you could, it turned out, appoint a detachment of digital commissars, tasked with removing ideological deviations from the online archives.

Browse old Vice articles on the website and you’ll periodically come across stories that have been discreetly memory-holed, replaced with this rather bloodless verdict: “We have concluded that this article does not meet Vice Media Group’s editorial standards. It has been removed.”

All of this airbrushing of the past for the sake of psychological safety in the present was a harbinger of the grimness to come, partly because it provoked no audible internal dissent and went unnoticed by the outside world. As one former executive recently told me, it was then that leadership should have reckoned with the disheartening reality that “our workforce hated our brand.”

Today on Honestly, Bari sits down with Michael Moynihan. Click right here to listen to that conversation: