The Free Press

American kids are the freest, most privileged kids in all of history. They are also the saddest, most anxious, depressed, and medicated generation on record. Nearly a third of teen girls say they have seriously considered suicide. For boys, that number is an also alarming 14 percent.

What’s even stranger is that all of these worsening mental health outcomes for kids have coincided with a generation of parents hyper-fixated on the mental health and well-being of their children.

What’s going on?

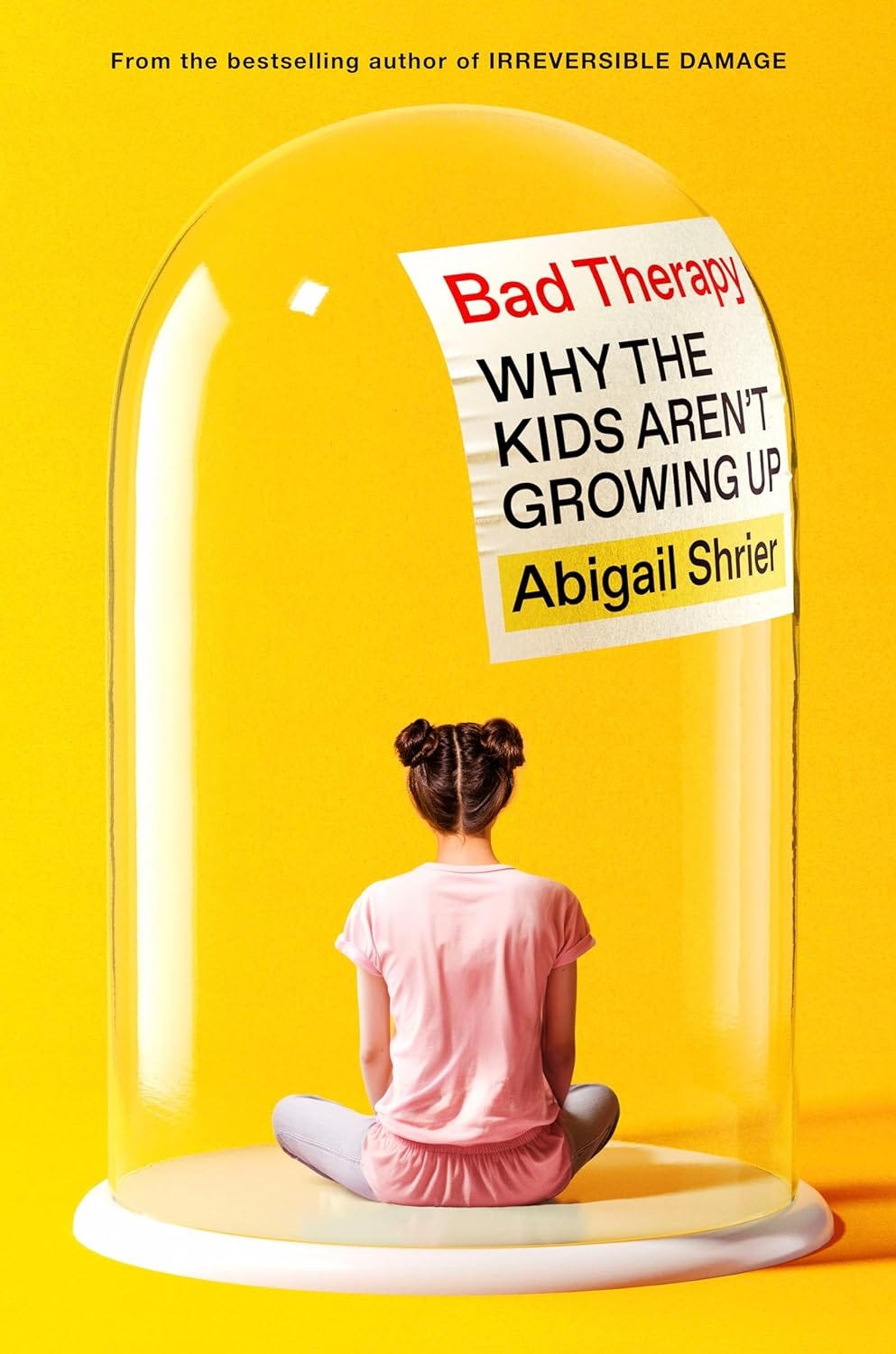

That mystery is the subject of Abigail Shrier’s fascinating, urgent new book: Bad Therapy: Why the Kids Aren’t Growing Up.

Longtime readers of The Free Press will surely know Abigail’s name from her groundbreaking reporting in our pages. She is also the author of the best-selling 2020 book Irreversible Damage, which tackled the difficult subject of the enormous rise of gender dysphoria among teenage girls. It was named by The Economist as one of the best books of the year and has been translated into ten languages.

In Bad Therapy, out today, Abigail heads into the breach once more. The book makes the case that the advent of therapy culture, the rise of “gentle parenting,” and the spread of “social-emotional learning” in schools is actually causing much of the anxiety and depression faced by today’s youth. In other words, Abigail argues that in our attempt to keep kids safe, we are failing the next generation of American adults.

The best journalists are fearless. And that adjective certainly applies to Abigail, whose bravery in following the evidence wherever it leads is what has made her work on some of the most important and controversial issues of the day so essential.

So read on for an exclusive excerpt from Bad Therapy. And if you want to hear my conversation with Abigail on the latest episode of Honestly, click below. —BW

Most American kids today are not in therapy. But the vast majority are in school, where therapists and non-therapists diagnose kids liberally, and offer in-school counseling and mental health and wellness instruction. By 2022, 96 percent of public schools offered mental health services to students. Many of these interventions constitute what I call “bad therapy”: they target the healthy, inadvertently exacerbating kids’ worry, sadness, and feelings of incapacity.

Since a child’s first mental or behavioral diagnosis often comes from school, the Child Mind Institute—one of the premier nonprofits devoted to adolescent mental health—provides an online “symptom checker” specifically to help parents or teachers inform themselves about “possible diagnoses.”

I began to wonder what schools were doing in the name of improving kids’ mental health. I was in luck. Each year, the state of California sponsors a three-day public school teachers’ conference to showcase its vast array of emotional and behavioral services. Immediately, I registered. That is how, in July of 2022, I came to join more than 2,000 public school teachers at the Anaheim Convention Center, right next to Disneyland.

At the convention, ankle tattoos winked over fresh pedicures, Anne Taylor cardigans abounded, and the occasional mohawk sliced indoor air cool enough to crisp celery. We talked about “brain science” based on a YouTube video many of us had seen. It explained that the brain is like a hand, with the thumb folded into the palm. “Our amygdala is really important in serious situations,” said the voice-over. This sounded right. We felt like neuroscientists.

We lamented the burdens placed upon school counselors, now part of an expanded psychology staff, which oversees every public school the way diversity officers dominate a university. We were leery of these new bosses, but we had to admit, they had a big job to do. Our kiddos were bonkers. (The word we were careful to use was dysregulated.) Counselors now routinely monitored the social-emotional quality of our teaching, sniffed out emotional disturbance in our students, and decided what assignments to nix or grades to adjust upward.

We talked about the need to give kids “brain breaks,” the salvific power of “Mindfulness Minutes,” and the importance of ending each day with an “optimistic closure.” Our purview was the “whole child,” meaning we needed to evaluate and track kids’ “social and emotional” abilities in addition to academic ones. Our mandate: “trauma-informed education.” We pledged to treat all kids as if they had experienced some debilitating trauma.

Subsequent interviews with dozens of teachers, school counselors, and parents across the country banished all doubt: therapists weren’t the only ones practicing bad therapy on kids. Often traveling under the name “social-emotional learning,” bad therapy had gone airborne.

When I first heard the term social-emotional learning, I assumed a hokey but necessary call for kids to get a grip. Or maybe it was the new name for what they used to call character education: treat people kindly, disagree respectfully, don’t be a jackass. Proponents insist it arrives at those things, albeit through the somewhat circuitous route of mental health. Sometimes described by enthusiasts as “a way of life,” social-emotional learning is the curricular juggernaut that devours billions in education spending each year and more than eight percent of teacher time. (Many teachers say they try to ensure that social-emotional learning happens all day long.) Through a series of prompts and exercises, SEL pushes kids toward a series of personal reflections, aimed at teaching them “self-awareness,” “social awareness,” “relationship skills,” “self-management,” and “responsible decision-making.”

Morning Emotions Check-in

Forget the Pledge of Allegiance. Today’s teachers are more likely to inaugurate the school day with an “emotions check-in.”

School counselor Natalie Sedano advised our assembled conference room of teachers to ask kids: “How are you feeling today? Are you daisy-bright, happy and friendly? Or am I a ladybug? Will I fly away if we get too close?”

This prompted great excitement in the audience, and teachers jumped up to share their own “emotions check-ins.” One teacher said every day, she asks her kids if they feel it’s a “bones” or “no bones” kind of a day, borrowing the verbiage from a viral TikTok video in which a pug owner shares the mood of his 13-year-old pug, Noodle. If Noodle sits upright, it’s a bones day! If he collapses, it’s a no-bones day.

“That is so fun!” Sedano enthused. “Love it! Thank you!”

I asked Leif Kennair, a world-renowned expert in the treatment of anxiety, and Michael Linden, a professor of psychiatry at the Charité University Hospital in Berlin, what they thought of practice. Both said this unceasing attention to feelings was likely to make kids more dysregulated.

If we want to help kids with emotional regulation, what should we communicate instead?

“I’d say: worry less. Ruminate less,” Kennair told me. “Try to verbalize everything you feel less. Try to self-monitor and be mindful of everything you do—less.”

There’s another problem posed by emotions check-ins: they tend to induce a state orientation at school, potentially sabotaging kids’ abilities to complete the tasks in front of them.

Many psychological studies back this up. An individual is more likely to meet a challenge if she focuses on the task ahead, rather than her own emotional state. If she’s thinking about herself, she’s less likely to meet any challenge.

“If you want to, let’s say, climb a mountain, if you start asking yourself after two steps, ‘How do I feel?’ you’ll stay at the bottom,” Dr. Linden said.

Ethical Violations

In 2022, California announced a plan to hire an additional ten thousand counselors in order to address young people’s poor mental health. A new law encourages California school districts to bill federal Medicaid for mental health services allocated to kids in school. Meaning, however much in-school therapy kids have already received, they likely will soon be getting much more. California school psychologist Michael Giambona provides individual therapy sessions to his middle school students during the school day.

Giambona also routinely runs interference with kids’ teachers on kids’ behalf. “My teachers have special training in working with individuals with behavior needs and mental health needs,” he told me. “And we meet weekly, and we talk about what’s going on with each student and how we can approach them and support them when they need it.”

There’s a problem with in-school therapy, an ethical compromise, which arguably corrupts its very heart. In a remarkably underregulated profession, therapists still have a few ethical bright lines. And among the clearest is—or was—the prohibition on “dual relationships.”

“The relationship in the therapy room needs to be its own, distinct and apart,” psychologist and author Lori Gottlieb explains in her book, Maybe You Should Talk to Someone. “To avoid an ethical breach known as a dual relationship, I can’t treat or receive treatment from any person in my orbit—not a parent of a kid in my son’s class, not the sister of coworkers, not a friend’s mom, not my neighbor.” This ethical guardrail exists to protect a patient from exploitation. A patient may reveal her deepest secrets and vulnerabilities to her therapist, who could then rule over her like a czarina does her kulaks. Anyone possessing this much knowledge of a patient’s private life may be tempted to exert undue power. And so the profession makes “dual relationships” off limits.

Except that school counselors, school psychologists, and social workers enjoy a dual relationship with every kid who comes to see them. They know all of a kid’s best friends; they may even treat a few of them with therapy. They know a kid’s parents and their friends’ parents. They know the boy a girl has a crush on, what romantically transpired between them, and how the relationship ended. They know a kid’s teammates and coaches and the teacher who’s giving him a hard time. And they report, not to a kid’s parents, but to the school administration. It’s a wonder we allow these in-school relationships at all.

The American Counseling Association appears to have noticed the obvious problem. In 2006, it revised the ACA Code of Ethics. While still prohibiting sexual relationships with current clients, it decided that “nonsexual” dual relationships were no longer prohibited—especially those that “could be beneficial to the client.”

As school counselors and psychologists came to see themselves as students’ “advocates,” they slipped into a dual relationship with their students: part therapist; part academic intermediary; part parenting coach. Today, school counselors and psychologists commonly evaluate, diagnose, and treat students with individual therapy; meet with their friends; intervene with their teachers; and pass them in the lunchroom. A teen who has just spent a tear-soaked hour telling the school counselor her deepest secrets might reasonably be fearful of upsetting anyone with that much power over her life.

But are school counselors and social workers exerting undue influence over kids?

Over the past two years, I have been so inundated with parents’ stories of school counselors encouraging a child to try on a variant gender identity, even changing the child’s name without telling the parents, that I’ve almost wondered if there are any good school counselors. One parent I interviewed told me that her son’s high school counselor had given him the address of a local LGBTQ youth shelter where he might seek asylum and attempt to legally liberate himself from loving parents.

There are good school counselors; I have interviewed several. But the power structure’s all wrong. Grant a leader the powers of a monarch, and he may gift his subjects freedom—but what’s to tether him to his promises? That’s placing a whole lot of trust in an individual counselor’s conscience.

You might respond at this point: fortunately, my child has never been to see the school counselor. But more likely, you don’t know. In California, Illinois, Washington, Colorado, Florida, and Maryland, minors twelve or thirteen and up are statutorily entitled to access mental health care without parental permission. Schools are not only under no obligation to inform parents that their kids are meeting regularly with a school counselor, they may even be barred from doing so.

As long as a parent has not specifically forbidden it, a school counselor may be able to conduct a therapy session with a minor child without parental consent. School counselors are encouraged to make “judgment calls” about what information, gleaned in sessions with minor children, they may keep secret from the children’s parents.

School Staff Who Play Therapist

Ever since her school adopted social-emotional learning in 2021, Ms. Julie routinely began the day by directing her Salt Lake City fifth graders to sit in one of the plastic chairs she’d arranged in a circle. “How is each of you feeling this morning?” she would ask, performing a more intensive version of the “emotions check-in.” One day, she cut to the chase: “What is something that is making you really sad right now?”

When it was his turn to speak, one boy began mumbling about his father’s new girlfriend. Then things fell apart. “All of a sudden, he just started bawling. And he was like, ‘I think that my dad hates me. And he yells at me all the time,’ ” said Laura, a mom of one of the other students.

Another girl announced that her parents had divorced and burst into tears. Another said she was worried about the man her mother was dating. Within minutes, half of the kids were sobbing. It was time for the math lesson, but no one wanted to do it. It was just so sad, thinking that the boy’s dad hated him. What if their dads hated them, too?

“It just kind of set the tone for the rest of the day,” Laura said. “Everyone just was feeling really sad and down for a really long time. It was hard for them to kind of come out of that.”

A second mom at the school confirmed to me that word spread throughout the school about the AA meeting–style breakdown. Except this AA meeting featured elementary school kids who then ran to tell their friends what everyone else had shared.

Thanks to social-emotional learning, scenes of emotional melee have become increasingly common in American classrooms. In 2013, The New York Times reported on a near identical scene that took place after a California teacher conducted a similar social-emotional learning session with his kindergarteners. “With children especially, whatever you focus on is what will grow,” Laura said. “And I feel like with [social-emotional learning], they’re watering the weeds, instead of watering the flowers.”

Advocates of social-emotional learning claim that nearly all kids today have suffered serious traumatic experiences that leave them unable to learn. They also insist that having an educator host a class-wide trauma swap before lunch will help such kids heal. Neither claim is well-founded.

But the predictable result is precisely what Ms. Julie saw: otherwise happy kids are brought low and a child seriously struggling has his private pain publicly exposed by someone in no position to remedy it.

Sometimes when a kid plunks himself down on the rug for morning circle, he is in no mood to exhibit a painful experience no matter how much it might expand the class’s emotional horizons. This leaves teacher-therapists with a problem: How to get kids to dish about their emotional lives when they really don’t want to?

One presenter at the conference, Amelia Azzam, a regional mental health coordinator for Orange County Public Schools, told a story that seemed to answer this quandary. She knew of a teaching assistant who trailed a seventh grader to lunch. She “goes out to lunch where this young student sits, and she always says ‘hi’ to him. And she has casual interactions with him.” And one day, he told her that his dad was getting out of jail.

“Nobody else knew that,” Azzam said.

Good therapists know that it may be counterproductive to push a kid to share his trauma at school. Good therapists are trained specifically to avoid encouraging rumination, a thought process typified by dwelling on past pain and negative emotions. Rumination is a well-established risk factor for depression. But school staff who play therapist rarely seem aware that they might be encouraging rumination as they stalk a kid at lunch, waiting to see if he’ll open up about his father’s incarceration minutes before a history test.

Injecting Anxiety into Math Class

Social-emotional learning enthusiasts happily disrupt math or English or history because, to the true believers, education is merely a vehicle for their social-emotional lessons—the corn chip that carries the guac straight to a kid’s mouth. “I can’t think of a content area that needs more social-emotional learning than mathematics,” educational consultant Ricky Robertson told our assembled conference room.

But how would a teacher manage to make social-emotional learning the goal of a math class? To discover the answer, I sat through a presentation titled “Embedding SEL in Math.”

Our mock lesson commenced with—you guessed it—discussion of our feelings about math. “Anxiety!” more than one teacher volunteered. The presenters showed us a series of kindergarten-level “math problems” that asked us to look at a bunch of shapes and asked: “Which one doesn’t belong?”

At the end, they revealed the correct answer: they all belong. No wrong answers! Everyone wins! See, that wasn’t hard.

I turned to the high school math teacher next to me and asked her how she could possibly incorporate this sort of approach into Algebra II. She stared back at me, a frozen rictus pinned to the corners of her mouth. She seemed to think Big Brother was watching us.

The only feeling apparently never affirmed in social-emotional learning is mistrust of emotional conversation in place of learning. A decent number of kids actually show up hoping to learn some geometry and not burn their limited instructional time on conversations about their mental health. But from every angle, such children could only be made to feel errant and alone.

In the minds of social-emotional learning advocates, healthy kids are those who share their pain during geometry. That is how a teacher knows they are emotionally regulated. They are willing to cry for the benefit of the class.

Excerpted from Bad Therapy: Why the Kids Aren’t Growing Up, by Abigail Shrier, in agreement with Sentinel, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © Abigail Shrier, 2024.

To support our work, become a Free Press subscriber today:

I posted two articles (https://www.israelnationalnews.com/news/282881 and https://www.israelnationalnews.com/news/297636 on Abigail's first book on Israelnationalnews.com's English site where I am op-ed editor and book reviewer. I would like to review this one, which seems necessary reading for parents. I could not find it at Israeli bookstores. Amazon takes forever and charges a fortune for shipping. Any help?

I had the honor of narrating the audiobook for Irreversible Damage (for which I received hate mail from some who obviously hadn't even read the book!) and Ms. Shrier painstakingly references the sources of all her info. She sounds a long overdue clarion call for parents...WAKE UP and demand transparency from your schools and your state governments! We have gotten to the level of the ridiculous and we are harming an entire generation of kids!!!