The Free Press

Nestled into the mountains of the Upper Valley in New Hampshire, up a semi-paved road in a house next to a tiny cemetery lined with white picket fencing, Fergie Chambers, 38, leans over his kitchen island, worrying over his commune.

“It feels like we’re throwing the same half-assed solutions at this over and over again and hoping it will yield something different,” he groans into his iPhone, which is on speaker. Fergie’s slight, but buff, on account of his multiple times a day martial arts training and competitions. His hair is cut short. A silver boxing glove dangles from one of his ears. He is covered in tattoos, including a double portrait of Stalin and Mao inked onto his thigh. He looks as if the phrase “Fuck you, Mom and Dad” were a person.

I offer my hand to a wheezing bulldog named Madison while Fergie talks over the phone to his employee in Alford, Massachusetts—the tiny Berkshires town where he’s bought 300 acres since 2019. Around 10 people live there at any given time. But he’s unclear—with me, possibly with himself—on what that place is exactly.

It’s a commune. It’s a “liberatory training space.” It’s a housing collective meets agricultural collective. It’s where the People’s Gym (“free for working-class people and permanently closed to cops, active military, landlords, and capitalists”) is located. It’s where the journal Combat Liberalism is based. It’s the headquarters for the Berkshire Communists group, which Fergie started. It’s where the Babochki Collective, the funding arm of all of Fergie’s projects, sometimes meets.

Fergie’s the General Secretary of the Berkshire Communists, which describes itself as a “revolutionary Marxist-Leninist collective, aiming to promote the formation of a powerful workers’ party.” But the urgent issue that late summer afternoon—before Hamas’s war against Israel; before Fergie called for “making people who support Israel actually afraid to go out in public”; before three of Fergie’s comrades were arrested on the roof of a weapons manufacturer in New Hampshire—was that 16 comrades were descending on Alford for a weekend retreat, and it’s been pouring rain. The canvas tents they pitched on the property are letting in water. A skylight in one of the six houses there is leaking. The punching bags in the barn-turned-gym are in the wrong place.

“It’s just that, I spent a lot of money so this would be done right the first time,” Fergie says, exasperated. Today, at least, the revolution requires fifty-dollar stall mats from Tractor Supply Company to line the floor of the tents and keep out moisture.

Then, he changes his tune. He apologizes—“I’m sorry I freaked out about the gym”—and then Fergie’s employee reminds him that when he drives over to the property tomorrow, not to forget the boxes of beekeeping equipment that were accidentally delivered to his house here, in New Hampshire.

“Right. I’ll probably forget them,” Fergie says.

“Well, I forgive you in advance.”

“You don’t have to do that,” he tells her. “You can hold it against me forever.”

He’s talking about the boxes, of course. But he could also be talking about the stupendous amount of money in his possession.

Fergie Chambers, an avowed communist since the age of 13, wants everyone to hold it against him forever that he is heir to an enormous fortune. And he’s willing to go to enormous lengths to tear down the mechanisms—capitalism, imperialism, liberalism, the rule of law, America—that delivered it into his lap.

That struggle has taken him from the charming cobblestone streets of his Brooklyn childhood to the mountains of upstate New York to the lake country region of Georgia to the Donbas region of Ukraine and now, back to the woods of the American Northeast, where locals say that his radical political organizing has taken a menacing turn, especially when it comes to the Jewish state on which he’s uniquely fixated.

“Make Zionists afraid,” Fergie wrote in a post on his Instagram on November 15. In another he wrote: “We need to start making people who support Israel actually afraid to go out in public. We need to make all of white America afraid that everything they have stolen is going to be burned to the ground. That’s what makes them listen.”

Since the war broke out, Fergie and his group have been organizing demonstrations around the country. Ostensibly they’re in support of Palestine—except members of the Berkshire Communists reportedly harassed a hardware store owner for selling Israeli flags and followed home employees of an Israeli defense company based in Boston. “No descendant of European settlers is oppressed, anywhere,” Fergie posted recently. “Not nearly enough, anyhow.”

A few Massachusetts residents have told me that Fergie, and those who live on his compound, amount to a “mob” and a “cult,” with Fergie playing the dual role of guru and sugar daddy—he bought the properties, paid for the gym’s remodel, and pays the rent of “comrades” who don’t even live there. He pays bail fees, too, when those comrades get in trouble with the law for their brand of “direct action.”

“A lot of people are just scared,” one resident of Great Barrington, the larger town that abuts Alford, told me, referring to things Fergie has posted online in recent weeks.

“There is nothing more disgusting than rich people who do nothing to undermine the material position of their own class vaguely calling for peace and love,” Fergie wrote on Instagram on November 2. “It gives me actual bloodlust.”

“We’re frightened to go out to restaurants, or cafés in town. It’s chilling,” the man in Great Barrington added. He tells me that the police aren’t much help—“they won’t come”—when it comes to Fergie and his followers, and that he’s considering moving towns. (The police declined to comment and directed me to the DA’s office who, through a representative, emailed to say that “District Attorney Shugrue is aware of the comments and posts James Chambers has made. He is actively communicating with local law enforcement and community leaders regarding Chambers’ behavior.”)

Almost all of the people I spoke to who live in the area around Fergie’s compound refused to go on the record because they said they are scared of retaliation. “People are getting panicky,” one neighbor said.

Local press coverage has focused on Fergie’s fondness for firearms. Many of his neighbors told me that the guns were what made them anxious. But a lot of people own guns. Fergie himself has claimed online that he’s “not a big gun guy” and told me over text that “I have like 4 guns,” and added, “I have a semi auto 40 cal Keltec [sic] that looks scary to liberals.” While he poses with guns online, and told me “I’ve always been into self-defense, and I was always kind of into guns,” he pushes back on the recent press coverage: “no one is raising a militia in Alford’’ and to say so is “a total deflection.”

It is the Berkshires itself that seems to be a powder keg. There’s a deep and growing tension in the “best small town in America”—especially since Covid brought an influx of second-home owners, driving home prices through the roof. There are very liberal colleges with very liberal students who want to take the theories they learn in the classroom into the streets. And then there’s Fergie, with hundreds of millions of dollars, eager to make it all go boom.

“If he was just a kook, that would be one thing,” a father in Great Barrington told me. “If he was just a gun-toting communist, that would be one thing. If he was just a millionaire, who liked to host young people and put a roof over their head and train them and indoctrinate them, that would be one thing. But it’s a completely different ball game when we’re talking about someone from a family that is arguably not only the richest in the county, but maybe richer than the whole county put together.”

Until very recently, by dint of his birth, Fergie owned a percentage of Cox Enterprises, a planet-spanning megacorporation, and the third largest private cable provider in the U.S. Over 50,000 people work there. The fact the Coxes still own the company outright makes them the eighth richest family in America, with a net worth around $34 billion.

It’s like if the Murdochs had double the money. But instead of Australia, they’re from America, and instead of conservative, they’re all—except for Fergie and a lone Republican aunt that no one talks to—establishment Democrats.

“[My great-grandfather] believed that business and private enterprise could do more to make an impact on the world than anything,” said Alex Taylor, Fergie’s cousin and the current Cox Enterprises CEO. He was onstage with Bill Clinton a few years back, announcing a $20 million investment in green initiatives on behalf of Cox. “I stand here today,” added Taylor “with a great privileged position, carrying on his legacy because of the way he set up his business and the way he set up his personal succession plan.”

That first Cox, James, the first one to count for anything, was born in a log cabin on a farm in Ohio in 1870 and bought the struggling Dayton Evening News at 29 years old for $26,000. That purchase was the beginning of what is today Cox Enterprises, comprising a network of radio stations, newspapers, television stations, and extremely lucrative automotive businesses: Autotrader.com, Kelley Blue Book, and Manheim auctions, the biggest car reseller in the world. In 2019, Cox invested $350 million in Rivian, an electric car company. In 2020, Cox Enterprises’ revenue was $19.2 billion, a slightly less profitable year than usual. Last summer the family bought Axios for over half a billion dollars.

In short, everyone in this family is spectacularly—obscenely—rich.

This past July, another of James Middleton Cox’s great-grandsons, Fergie—born James Cox Chambers and brought home to The Dakota apartments on the Upper West Side of Manhattan—traded in his shares of Cox Enterprises so he could make an investment of his own. Like his great-grandfather, he believes money can change America. So this summer he lost his chains. He believes that by extracting himself for good from the web of trusts, tax-shielding entities, accountants, asset managers, and the family office, he can undo their American dream.

The immediate reason for this break, he told me, was the cops.

Specifically, Cop City, officially known as the Atlanta Public Safety Training Center, a complex that’s being built outside Georgia’s capital city to “provide better opportunities to train on more socially just models of policing and crisis intervention.” Alex, the Cox CEO, is the lead fundraiser for Cop City as the honorary chair of the city’s police fund. Fergie, his cousin, is now the lead fundraiser on the other side; he’s said he’s already given $600,000 to fund the referendum against Cop City as of July, another $250,000 to the legal defense fund of the protesters arrested there, and another $350,000 to an “abolitionist, not-for-profit media collective.”

On Alex’s side: reforming the police. On Fergie’s: abolishing them altogether.

Alex loves fly fishing for wild salmon and his agenda for Cox includes promoting “connectivity, mobility, and sustainability.” On Fergie’s agenda this weekday afternoon is picking up 22 joints from a dispensary in Vermont and a few grass-fed steaks down the road. So the self-identified class traitor and I climb into a Tacoma truck with New Hampshire vanity plates that read CCCP—the Russian transliteration of USSR—and that reeks of weed already.

Idyllic A-frame houses are whizzing past the driver’s window when I ask him about the straw that broke the camel’s back, and how he came to be Merry Levov with neck tattoos and a blue belt.

“I started tweeting like, my family are enemies of the people with their full names. Like ‘Fuck these motherfuckers,” Fergie tells me. That happened in the late summer of 2022. Fergie never quite fit in with his family, and the lifetime of screaming fights over politics at sushi restaurants in Manhattan, tense interventions in Palm Beach, and endless and expensive wilderness therapy programs for troubled teens in Utah seemed to finally be coalescing into an identity of his own.

Alex called Fergie and offered a compelling proposition that fall. “My cousin called and said getting out was an option. We can do it right, and here’s the offer.”

Nine months later, in May 2023, Jim Chambers, Fergie’s dad and Alex’s uncle, was giving the opening remarks at Bard College’s commencement, where he cuts a figure as the normative liberal, if cartoonishly hippie-ish, chair of the board. “When are we as a species going to stop fearing love?” he asked, a rope of gray dreadlocks snaking down the back of the red graduation gown. Chambers called to “cleanse our dirty ways of polluting mama earth,” before announcing, “Life is hardcore, but so is love.”

Shortly after, the main speaker, Georgia senator Raphael Warnock, was disrupted by protesters screaming “Stop! Cop! City!” Fergie was one of them. His daughter held one side of a massive banner that read “HEY WARNOCK: STOP COP CITY FREE PALESTINE.”

“That was the first time I saw my dad in two years, and the last time I saw him,” Fergie tells me of the incident.

A month later, after months of lawyering, nearly a year after his cousin had called, the deal was signed, and the first direct deposit came through. Fergie was free.

Though part of the terms is that he can’t get into exact amounts or how many shares he sold with a reporter, he tells me that he received north of $250 million dollars, which is likely less than he would’ve gotten if he stayed entwined with the company—he says they paid him thirty cents on the dollar per share. But still, a quarter of a billion dollars. He was given half of that earlier this summer and the rest will be doled out over the next 14 years. “I had money before. I had a lot of money,” he says, “but I didn’t have A LOTTA money.”

The question now was: What the hell was he planning on doing with it?

“Do you think there’s any chance that Ben knows what broccolini is?” Fergie screams out to his daughter while texting, emerging from the laundry room.

Ben is the twentysomething son of one of Fergie’s local jiu-jitsu coaches, and his new personal assistant. He resisted hiring help to manage the four dogs, four kids by two women, and the half dozen or so houses spread across the northeast and Atlanta. But now there’s so much money, and so many requests from comrades and strangers—for gas, to pay rent, to help cover someone’s divorce lawyer—so he’s staffing up. In addition to Ben, there’s Nick, a fixer hired away from the family office in Atlanta, “to do shit I don’t know how to do.”

Things like figuring out commercial leases and zoning and permits. Fergie recently spent half a million on 5,000 square feet in an office park near his house in New Hampshire and is setting up the Upper Valley outpost of his People’s Gym. So far, he’s spent north of $5 million amassing acreage for the compound in Alford through the LLC “Cloud Kingdom.”

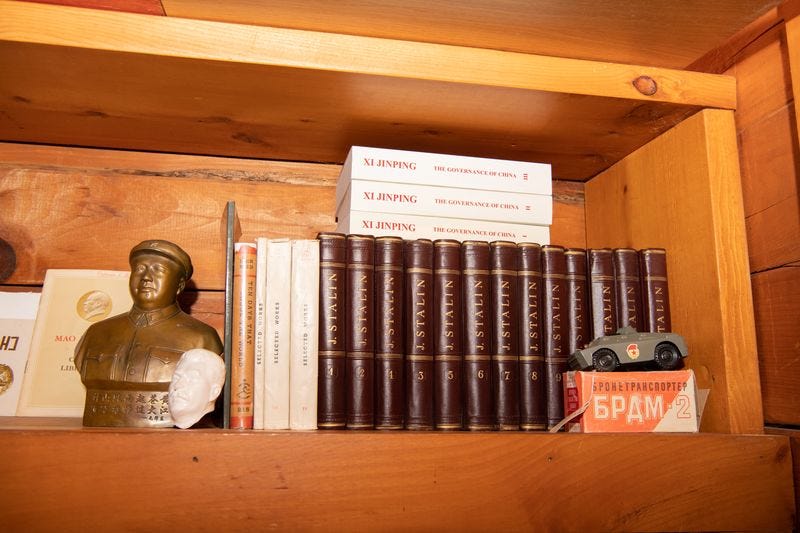

Fergie’s New Hampshire house, where he spends the lion’s share of his time, is modern; no walls, all blonde wood and sweeping views of the wet mountains bursting with late-summer green. The bookshelf is stacked high with dozens of copies of The Communist Manifesto and Xi Jinping’s The Governance of China. There’s a framed picture of Fidel Castro above a mini fridge cooling raw milk. A shotgun hangs on bike hooks along one of the rafters.

Fergie is pulling espresso shots on a nearly $6,000 Italian coffee machine when his older daughter, Anne Margaret Chambers, 14, with a neck full of hickies and wearing a ripped Pierce the Veil concert t-shirt, trips up the stairs from the basement to make herself two cheese quesadillas. Fergie’s other two kids from his first marriage, Nadya and James, live with their mother in Atlanta.

In addition to Fergie and Anne, Stella Schnabel, 39—daughter of the painter Julian, sister of the art dealer Vito—Fergie’s on-off partner, lives here, along with the pair’s two-year-old son, Viktor Gonzo Cox Schnabel Chambers. They’re all still getting their bearings in New Hampshire. They only moved here from Alford this past January for its lax gun laws and low tax burden, after Fergie decided to cash out.

“I don’t want to pay taxes to Uncle Sam,” Fergie tells me. “Objectively, somebody like me should pay almost all of their money in taxes, but if I can legally evade giving that to the U.S. war machine, I will.”

He was drawn back to the Northeast after a decade or so sojourn in Atlanta, the later years of which he presided over another land project: 350 acres in Madison County, Georgia that he dubbed “The Free State of Palestine.” Fifteen people lived there. The main house, where Fergie lived, was called “Jerusalem.”

The Free State of Palestine, Georgia, fell apart along with his second marriage; Fergie was charged with weed possession at a friend’s funeral. He said that he and his wife were both on probation, and his friend, who was a federal fugitive who had lived at the project, died. It was time to go, time to come home. He referred to that time in Georgia as a “Christ-like wilderness” in a Facebook post in 2019, which was partly written in the third person: “Fergie was and is a maniac, an intentional mask-wearer, someone America calls ADHD.”

There are other whiffs of a messiah complex—or at the very least, evidence of an overactive mind disposed to conspiracy. Fergie stares at the radio when a Steely Dan song called “My Old School” comes on in the car. “Weird,” he pauses for a moment, taking in the song. “This is about Bard.” He points out, in the same breath, that Cox Enterprises consults for the Department of Defense and that they also invested in telehealth platforms right before Covid hit and tells me over the phone that he believes that his family has his house bugged. “Do they see everything on my phone? Probably.”

He’s not being a “paranoid freak,” he says. “My family is a bunch of fucking billionaires who have admitted to having me followed.” But he also admits to me that he had his own wife—the second one—followed, when he worried she was having an affair.

Once rich never poor, the saying goes, and with Fergie you can tell. He interrupts and embellishes. He remembers petty grievances like the time his dad got him a low-value Sharper Image gadget one Christmas, or when his Aunt Kathy, who he calls “the meanest person in the world,” accused him of stealing thirty dollars twenty years ago. He insists that he was his grandmother’s favorite, and that she would have wanted him to take over the company.

In fact, he worked on a Manheim car auction lot for a year when he moved back to Atlanta, in an attempt to earn his keep within the firm. He calls it his “fringe, too-precocious, theocratic, proto–alt-right” era, though today he’s swung back fully to the hard left.

“I’ve learned to silently wait, and evade, but if need be, to kick them in the heads and submit them on the ground,” Fergie wrote in that 2019 post. “I came to wear whatever mask I want to put on today, to make noise, be in the trees, and fuck America in its dead, rotting face.”

It’s Wednesday, and Fergie is rolling joints in the kitchen. His partner Stella—statuesque, in leggings, and with her dark hair in a bun, just back from a month in the Hamptons with their son—is directing a team of movers who are shuffling around plush jewel-green sofas that were trucked up from her Brooklyn storage unit.

“He has his plate full,” says Stella, when I ask about whether she gets fed up with all the projects Fergie seems to be cooking up. He had just told us about a nearby mine that was up for auction that he wanted to buy. Stella adds: “I wouldn’t say managing people is his strong suit.”

“That totally depends though, actually,” Fergie interjects, popping his head out from the kitchen. “I run a gym staff very well.”

Before the couple pauses for a make-out session, I ask about the communist elephant in the room. When I had told the innkeeper in Hanover where I had stayed overnight what I was doing in town—spending time with a rich communist—she said this: “Screw him, he doesn’t know what he’s talking about.”

“When certain friends of mine, or ex-friends, start critiquing him, and if they have any money, I’m like, Well, I’d love to know where you’re putting your money,” says Stella, whose own dad is worth an estimated $25 million. “Are they giving their fucking money away? Are they giving money to people in Jackson to clean their water?”

It gets complicated, this type of thing. “I grew up in a world where everyone’s kissing your ass for something you didn’t do. And it’s the same thing when you’re super fucking rich.” She describes her father, Julian, as “really charming, and super generous and totally annoying and fucked up at the same time.” She sighs. “Yeah. Whatever, as you know, dialectical materialism. . . there are always opposites.”

Fergie’s own parents split up when he was two. His dad and the business were based in Atlanta; Fergie was raised in a Brooklyn brownstone with his mother. A consummate problem child, he went to St. Ann’s, a very expensive and alternative private school for the children of the city’s rich but artsy class. (Lena Dunham is a graduate.)

It was there that Fergie was introduced to communism, thanks to an eighth grade history teacher. But he tells me he didn’t even know he was wealthy until a classmate showed him the Forbes list around the same time.

So he did what any good young revolutionary who found out he was the heir to a fortune would do: he emailed Noam Chomsky. “I think he suggested some books to read,” Fergie tells me. He doesn’t remember which and tells me that nowadays, “I don’t fuck with Noam Chomsky.”

Fergie’s always tended to gravitate toward the hard stuff. Combat sports. Guns. He takes his steak raw, slathered with raw honey and butter. He tells me that he was shooting up heroin at 14, sobered up by 16, but then at 18 he was cooking crack in the shared kitchen at the dorms at Bard. He was asked to take a leave of absence for the crack incident. After a booze and drugs binge ten years later, in 2013, he was arrested on domestic battery charges.

He has a tattoo on his face. It’s a lightning bolt with an arrow on the end of it, a keepsake from a moment during a mushroom trip he had during a blizzard at the protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline at the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in 2016. “It was like revolutionary suicide,” he says. “There was no question that I’ll be doing this to the death.”

He was, seemingly by nature, anti-everything his genteel family stood for.

James Middleton Cox, the original patriarch, was the Democratic nominee for president in 1920—FDR was his running mate—and two-time governor of Ohio. Fergie’s grandmother, Anne, the only Cox Fergie seems to have anything nice to say about—“She was a bad mother and an absent WASP, but she was not cold as a grandmother”—was the ambassador to Belgium under President Carter. She had a cardboard cutout of Obama in her living room, and she took her private plane to canvass for him in 2008. She sat on the boards of the Met, the Whitney, the Atlanta Symphony, and went to Miss Porter’s. She was once worth $17 billion.

But thanks to some clever estate planning, when she died in 2020 at 100 years old, Fergie only got $6 million, a Chagall painting of a goat herder, “and some forks.” The rest was divided between Fergie’s dad and aunts.

Fergie’s father, the eldest boy, is a progressive for his time and a black sheep in his own right. He was a dance major at Bard, and believes deeply, I am told, in the power of chiropractic medicine. He is also a vegetarian and a biodynamic farmer (his farm, Honey Dog, is 15 minutes down the road from Fergie’s Massachusetts outpost) and he is obsessed with bees. He’s married to Nabila Khashoggi, daughter of Adnan, the infamous arms dealer and once the richest man in the world. They have one son: Ulysses Layth Adnan Cox Khashoggi Chambers.

“They’re kind of lazy, rich people,” Fergie tells me. (Jim Cox Chambers, Fergie’s father; Lauren Hamilton, his mother, an artist who lives in upstate New York; and Cox Enterprises did not respond to multiple requests for comment.) “They just wanted me to be this liberal and I’m never gonna be a liberal,” Fergie says.

“See ya later, fucker!”

We’ve packed up and we’re on the highway racing down to Alford, Massachusetts from New Hampshire, about a three-hour drive, and a cop car that Fergie had his eye on just zoomed by. He won’t go into detail about the retreat we’re heading to and who is coming but says he wants to bring together “people who are already active in different organizations” to cook, eat, learn about Marxism, and train in martial arts.

Anne, the 14-year-old, is sitting in the back of the truck—this one has a “Henry Ford Was a Literal Nazi” bumper sticker—eating Subway and listening to the Foo Fighters on her AirPods.

“I don’t want to be an overbearing parent but as far as I’m concerned, there’s not really another acceptable option for someone in our position than devoting most of one’s energy to the dismantling of the system that created us,” says Fergie. That’s why he doesn’t just give $2,500 to 200,000 people and call it a day. The wheels of capitalism would keep turning, and Fergie wants to wedge an anvil into the spokes.

I ask Anne, who recently dyed the front of her hair blue—“there’s not enough emos in the world,” she laments—if she has the same politics as her dad. “I think it’s good to understand that it’s totally unjust that we have that money in the first place.” Even though Fergie thinks it’s “ridiculous” for anyone of their wealth to have a normal job, Anne works front of house at a local restaurant in New Hampshire.

It seems exhausting to be in a constant state of self-annihilation, at once achingly lucky and eternally angry. Even other bleeding-heart rich kids who disavow their wealth, like Abigail Disney or Leah Hunt-Hendrix, an heir to an oil fortune who started Solidaire, and support progressive political causes like the Green New Deal and the congressional campaigns of certain Squad members, do it from within the system. Fergie hates all that. He has no interest in joint statements or slow change, small wins, or baby steps.

“They’re getting in rooms where they’re like, ‘Oh, I’m a really rich kid and I don’t know what to do about it so I’m gonna sit at a table with a bunch of other rich people, and we’re gonna decide together.’ Bro. This is revolutionary?” Once Democrats get involved, he says, “any good motivations go to hell.”

Absent a formal sounding board, any real executive team, or an established philanthropy under him, Fergie relies on Zooms with a “council” of trusted friends and activists—he wouldn’t give me their names—for advice on what to do with his money. At various points he’s been involved with The People’s Forum, the Black Alliance for Peace, the DSA, and different people on the ground in Atlanta. And there’s his Babochki Collective. But really, he can do whatever he wants. He’s constantly rebranding and reconfiguring his outward-facing groups: yesterday it’s Cloud Kingdom, today it’s Berkshire Communists. He’s had his fallings-out before. When it comes to the money, at the end of the day, he’s in control.

“I couldn’t blow the money before because it was in the Cox mechanism and was doled out,” he says. I ask if he’s nervous now that the first lump sum has been transferred. “Of course I’m scared. Like, did I make the wrong choice?” he says, eyes darting around for more cop cars.

“I’m thinking, what if I make the wrong decision with it?”

Even more than imperialism, liberalism, idealism, capitalism, the cops, the 12 steps, psychopharmacology, his dad, and America—all of which he despises—Fergie hates Israel.

The war that broke out on October 7 when Hamas attacked Israeli civilians gave him the perfect opportunity to put his money where his mouth is—to let the world know where he stood on the Jewish state. Mostly the world has meant his neighbors in New Hampshire and Massachusetts.

People around town have known about Fergie for as long as he’s been here. There was a separate protest in 2021, during the last bout of violence between Hamas in Israel, where comrades held up signs that read “Death to Amerikkka,” which raised eyebrows. But the Great Barringtonians I spoke to say they’re more scared than they’ve ever been since a rally he organized in town on October 10.

“I didn’t feel personally threatened until that rally,” one neighbor tells me.

At that rally, he and the Berkshire Communists held signs that read: “End all U.S. aid to Israel” and “Israel and U.S.A. = Terrorists.” When asked by a reporter at The Berkshire Edge if he supported Hamas, Fergie answered in the affirmative: “Yes,” and added, "Hamas is an indigenous anti-colonial resistance group.” How about the specific events on October 7, where 1,200 people were murdered, women raped, and others burned alive? “The Al-Aqsa Flood was a powerful statement of resistance to genocide,” he said.

On X, he was even more forthcoming about the massacre: “One month ago today, the Palestinian Resistance heroically jolted the occupiers, eliminat[ing] a number of combatant settlers,” he wrote. He does not believe civilians were targeted on October 7 in Israel and denies rape took place, writing, “the resistance is principled. The resistance is devout.”

Fergie has publicized that he’s given hundreds of thousands of dollars to groups including the Middle East Children’s Alliance, to the anti-Zionist writer Philip Weiss, and to Samidoun, which Israel designated a terrorist organization and which Germany recently banned. (Samidoun has ties to the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, a Marxist-Leninist group designated as a terrorist organization by the United States, Japan, Canada, and the European Union.)

That October 10 rally in Alford was just the beginning. A few days after that protest, Fergie and two Berkshire Communists members—Paige Belanger and Calla Walsh—chained themselves to the entrance of the Cambridge office of Elbit Systems, an Israeli-based weapons manufacturer. Then, on October 20, he was speaking to a crowd from the bed of a truck in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, protesting General Dynamics. More Berkshire Communists—who have spun off, semantically, as Palestine Action U.S.—were arrested at Elbit in Boston late last month but were bailed out later that night. Fergie told Los Angeles magazine that he paid their legal fees. A few days later Fergie was arrested in Washington, D.C., for defacing a McDonald’s (“Free Gaza” was spray-painted on the facade and the windows were broken). Over the past few weeks, he’s been down to Atlanta to demonstrate and organize against Cop City and up to New Hampshire to attend a teach-in at Dartmouth.

Throughout, he’s been posting things like “death to the normalizing left,” which Fergie wrote recently in reference to the far-left group Jewish Voice for Peace. He ruminates in another post: “In the future there will be no Israelis.”

“This just changes everything. It just changes everything,” one neighbor says of Fergie’s posture toward Hamas. She told me she feels threatened by him—and scared. “The idea that everything is justified? Well, then, what does that mean for your neighbors, like what’s justified?” She adds, “How many guns does he have stockpiled here in Alford?”

“This is life or death,” says another community member, who has beefed up security at his own house—he’s purchased cameras, floodlights, a dog—since Fergie arrived on the scene.

“He’s got enough money to ruin my life. I have a business, I have a family that I love,” he says. “I just want a comfortable, quiet life.”

Berkshire and Columbia counties, both east of the Hudson River, may seem bucolic from the outside, but residents tell me there’s roiling class resentment under the surface between wealthy second- and third-home owners who come in from the city and the locals who have been priced out of the area.

A few locals, like Regi Wingo, a hip-hop artist who volunteered with programs for troubled youth, have been given free housing on Fergie’s commune. At the rally on October 10, Wingo held a sign blaring “When people are occupied, resistance is justified.”

“That was hard for me to see him holding that sign, even though I know Fergie is probably paying him off,” said one of the neighbors, who has known the Wingo family for decades. Regi’s 19-year-old daughter Athena lived on the commune with him, but she has since left.

Other Berkshire Communists include Sage Radachowsky, a Harvard-trained biologist, to whom who Fergie gave money to build a house, and Paige Belanger, 32, who, according to her Instagram, is a “political educator, agitator, and herbalist,” and the secretary of Berkshire Communists.

There are the brothers Sam and Ben Catechi. Ben, now 22, was once a student at Bard College at Simon’s Rock, a junior college in Great Barrington with a hyper-progressive reputation that a resident tells me is “ripe” for Fergie’s recruitment. Simon’s Rock parent school is Bard, where Fergie’s dad is the chair, and where the alumni center is named for his grandmother.

“There is a matrix of connections between my family and Bard,” Fergie’s dad Jim said at the dedication ceremony for the baseball field he donated for $2.2 million.

It’s unclear how many Berkshire Communists members are from the school, where kids can enroll as young as 15, but a pro-Palestine protest earlier this month was organized by a coalition of Simon’s Rock Student Groups and the Berkshire Communists (on this score, Fergie tells me over text, “I didn’t organize that, I wasn’t even there” and says there’s “zero” relationship between the Berkshire Communists and Simon’s Rock).

But several Simon’s Rock students told me that they’d heard of Fergie, or his group, or that their friends work out at the People’s Gym. One student said she’s noticed “alarming behavior” among her classmates. “Through discussion with one extremely left student, it was explained to me that they believe we need to start collecting firearms to ‘arm the proletariat’ for a coming revolution.”

The response to all of this from institutions in the area—especially Jewish ones—has been lackluster, according to the locals I spoke with.

A concerned community member emailed Simon’s Rock but worries they aren’t taking Fergie seriously: “It’s negligent.” One source said he complained to the local Jewish Federation chapter and was told to keep quiet, lest donors become spooked and the Berkshires get a bad rap. (The Federation’s executive director for the Berkshires chapter, Dara Kaufman, did not respond to multiple requests for comment.) The local Chabad rabbi, Levi Volovik, in nearby Pittsfield, said a few community members have approached him about Fergie. “He wants everybody to be nervous,” the rabbi told me over the phone, but he doesn’t seem too perturbed himself. “Why should anybody be nervous?” He added, “In a time of darkness, it’s time to add light.”

Alford, which has a population of 486, doesn’t have a police department, but neighboring towns, like Great Barrington and Pittsfield, do. But when community members go to the local police claiming that Fergie is inciting violence, they tell me they’ve been told that Fergie has a right to protest, and to free speech, and there’s nothing they can do despite the noxious messages he puts out. They’re told that the local and state police and FBI are aware of the commune, and are keeping an eye on him, but the residents feel, they tell me, like it’s getting “lawless” in Great Barrington.

There are also the things that have happened in the area that can’t be traced directly to Fergie. A local synagogue received an anonymous call, and the voice on the other line said, “Shabbat Shalom. Allahu Akbar.” A year ago, the town woke up to a billboard scrawled with graffiti: “Eat the rich,” and another, “No one needs two homes.”

Leigh Davis is the vice chair of the town’s five-person Selectboard, which sets policy in the town. She says Great Barrington—ten minutes from Alford and with more than ten times the population—is “very progressive” and that other towns often look to it as an example. She heard of Fergie a few years ago when he moved to Alford but didn’t think much of him. “I didn’t feel like it was something that needed our attention.”

But since the war broke out, and then the protests in front of town hall, her constituents have been reaching out. “Here’s this incredibly wealthy person that’s sitting on millions and millions of dollars saying he’s fighting for the poor,” she told me. “There’s a real worry of ‘Where could this go?’ ”

To constituents Davis says, “My silence is not due to a lack of compassion and solidarity. We are listening and we do care, but there’s only so much we can do as the Selectboard.” She also doesn’t want to inflame the situation or antagonize “the hornet’s nest” of his commune. “It’s a balancing act.”

For his part, Fergie posted a message directly on Instagram to Great Barrington residents who feel threatened by him: “You are rich white [E]uropean settlers in a cultural resort town.” The working class are “coming for you one day soon,” Fergie predicted, and once that happens, “There won’t ever be enough cops to call.”

A local told me that she worries about her neighbors being drawn into his far-left ideology, which posits that the struggle of Palestinians is the same as that of working people everywhere, including in Berkshire County, where she says they feel edged out. “I think people are feeling peer pressure here,” she says. “Very good, ordinary people, who don’t have the means to find their way out get sucked into things.”

“My fear is that he will get more supporters, and they will get more radical,” one resident said. “And that this will end in an ugly and violent way.”

On Monday, November 20, three protesters were arrested at another Elbit Systems office building in Merrimack, New Hampshire. They had smashed windows, splashed the facade of the building in red paint, and climbed to the roof of the building to set off smoke bombs. They also bike-locked the doors of the office shut, locking employees inside, who called the police around 8 a.m.

All three are a part of Fergie’s group—“those are comrades,” he texts me, and all young women: Sophie Ross, 22, Calla Walsh, 19, and Bridget Irene Shergalis, 27. Ross appears, it seems, in the Simon’s Rock yearbook for the 2019–2020 school year, alongside Ben Catechi.

Walsh was previously locked to the Elbit office building in Cambridge alongside Fergie in early October, and was arrested there, along with Ross, for vandalizing property and disorderly conduct a few weeks later. Before this recent string of arrests, she worked for Elizabeth Warren’s and Bernie Sanders’ campaigns as a teen activist. Her parents are both professors. In 2021, The New York Times, in a write-up, called her part of an “influential new force in Democratic politics.”

The next day in the Hillsborough County Superior Court South, in blue masks and orange jumpsuits, all three women were charged with riot, sabotage, criminal mischief, criminal trespass, and disorderly conduct. Walsh and Ross were given $20,000 bail, owing to their recent prior arrests, while Shergalis was issued $5,000 bail.

Fergie paid for all of it.

“We ALWAYS post bail for those facing state repression for radical politics,” he texted me, in reference to Babochki, the funding collective that distributes his wealth. He added that “I don’t wanna mess w[ith] any legal scenario” and “many people in this country are responding to this genocide in a variety of ways.”

When Walsh was released, Fergie posted a picture of her on X with the caption “Heroic Glow.”

The governor of New Hampshire, Chris Sununu, said in a statement, “I am confident law enforcement will work to bring those responsible for this vile act of hate to swift justice.” I’m told by the DA’s office that a separate state police detective unit has been assigned to monitor the Fergie situation. And last Monday, Alford’s building inspector sent a letter to Fergie and his lawyers accusing him of breaking zoning bylaws with his People’s Gym, writing, “This office has previously contacted you about the above referenced address and, specifically, use of the structure thereon for purposes other than storage for which it was permitted.” Fergie calls the move “ridiculous and targeted.” He says cops have been driving up and down the road near the properties and added, “[I]t’s not commercial, it’s not crowded, it’s us using a big building on an 80-acre property to move around with friends.” Online, he blamed the “Zionist frenzy smear articles” for the efforts to shut down his gym.

Timothy Shugrue, the DA, said this about the unrest Fergie is raising: “These hateful actions are inconsistent with basic civility, inclusivity, and respect. As district attorney, I will take all efforts to ensure the safety of all citizens of the county. We will vigorously prosecute any and all hate crimes against any citizens of our county.”

But Fergie’s neighbors, the ones who live near his compound, are confident this will have a different ending.

“This community is going to have a disaster. There will be a crazy kid who gets ahold of a gun who does something bad. And Fergie will pay for his lawyers. He’s got the money. It will ruin the Berkshires,” says one of them. He worries that everything that’s happened with Fergie so far is “just the prologue.”

Editor’s Note: Fergie Chambers reached out after publication to clarify that he did not have his wife followed because he suspected she was having an affair. He hired a private investigator to confirm her location because he was worried about her. The Free Press regrets the error. In addition, Fergie made clear that his grandmother, Anne, wouldn’t have wanted him to run the company, because “that wasn’t me ever.”

Suzy Weiss is a reporter at The Free Press. Her last story was about young Western women converting to Islam.

If you appreciate stories like this one, support The Free Press and become a paid subscriber today:

Rich commie. Didn’t make his money, got daddy’s.

Charles Manson with LOTSA money.