The Free Press

On Wednesday, or “Liberation Day” as he called it, President Donald Trump announced a “declaration of economic independence.” By which he meant, of course, that the time has come to impose tariffs on America’s trading partners the likes of which had not been seen since the Smoot-Hartley Act of 1930. Surrounded by steel and auto workers, Trump held up a chart listing America’s trading partners and what he claimed were the percentage of the tariffs and non-tariff barriers they placed on U.S. goods. In the coming days, he said, the U.S. would slap tariffs on every country that was half as high as the ones America faced—except for imported autos, which will face a 25 percent tariff no matter what country they come from. This, he said, would lead to billions of dollars in investment in the U.S. and bring lower prices and greater prosperity.

Matthew Yglesias begs to differ. In this article, which we’re reprinting from his Substack Slow Boring, Yglesias explains why there is only thing we can know for sure about Trump’s tariffs: They will lead to higher prices. To subscribe to Matthew’s blog, which we promise is neither slow nor boring, click here.

—The Editors

It was clear for a while that our family would soon need to buy a new car, and we’d decided, for various logistical reasons, that the ideal time to do so was early April of 2025 and that the right car for us was one that happens to be made in Europe. For most of 2024, that was our plan.

Then in January of this year, Kate got nervous that Donald Trump was going to impose tariffs that would lead to higher car prices, and she wanted to accelerate our plans. My personal view was that this was unlikely; I thought Trump was mostly bluffing and would be eager to settle trade disputes for small concessions. But in my experience, it’s good to listen to your editor, and there was no real harm to accelerating our plans, beyond a minor parking inconvenience.

And that turned out to be the right move, because Trump has followed through on his threat to impose big taxes on imported cars and car parts. To address voter anger over higher prices, he “warned automakers not to raise prices,” which seems to me like something that will probably not work.

And it’s not just Trump singing this tune.

The United Auto Workers (UAW) has decided that it is enthusiastic about tariffs. But in the UAW’s statement endorsing Trump’s move, it said that “auto companies that have enjoyed years of record profits should absorb the cost of these tariffs rather than passing them on to consumers, and the UAW would support legislative or regulatory action requiring them to do so.”

So here I want to emphasize something: There are lots of different ways that tariffs could play out. Some of those ways could lead to large increases in consumer prices, and some have smaller or near-zero price effects. But to the extent that tariffs successfully protect high-wage American jobs or drive new investment in creating such jobs, the mechanism through which they succeed is higher prices. If the prices don’t go up, then the things that Trump is touting as the benefits of tariffs also don’t happen.

The high prices are the protection.

Jawboning Automakers Isn’t Going to Work

Trump is pursuing an approach to price-setting that is traditionally called “jawboning,” where, short of formal price controls, the government strongly suggests to companies that it would be in their interest to keep prices low and that, if they don’t, they’ll face some sort of retaliation.

Jawboning can absolutely work in a range of contexts.

Apple, for example, has very high margins, a lot of practical control over the retail price of Apple products, and a wide range of regulatory issues and policy concerns before the federal government. You could absolutely impose a modest tariff on imported iPhones and then lean on Apple to just eat the losses. Governing the country in this Peronist style could have various negative consequences, but I do think it would narrowly work.

But with autos, I don’t see it.

Consider the case of a company like Audi, which sells a lot of foreign-made SUVs in the United States. If it doesn’t raise prices, then suddenly selling an Audi to an American customer becomes a lot less lucrative than selling the exact same car to a customer in some other country. The reasonable course of action would be to redirect some of the cars to foreign countries—cutting the price of Audis abroad somewhat (but by less than the tariff rate)—and ship fewer units to the United States. Then on the flip side, you have a company like Ford, whose SUVs are made in the United States. With fewer foreign-made vehicles available for sale in the United States, demand for its SUVs is going to be higher.

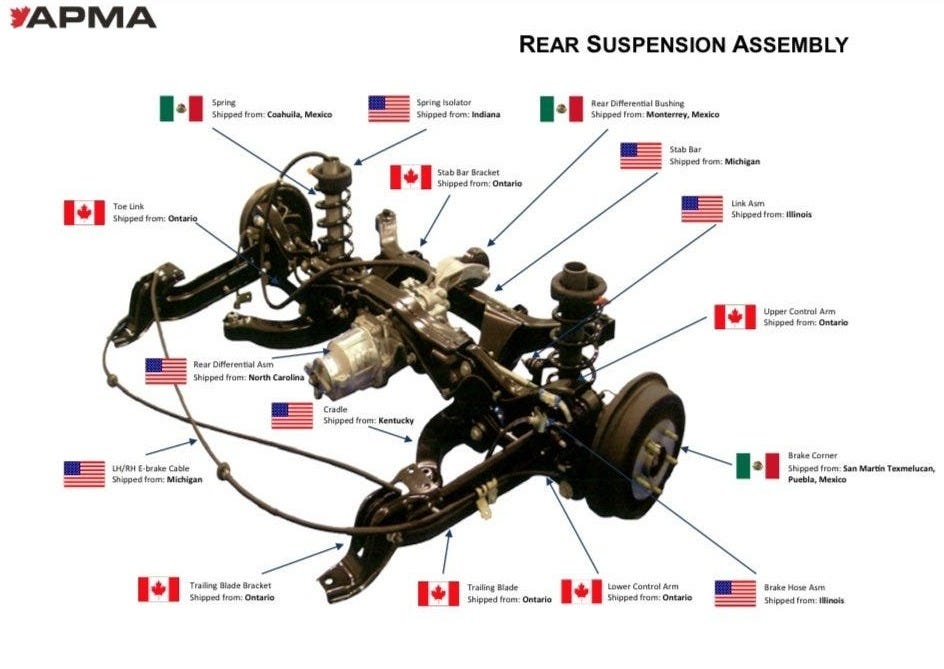

There are also, because vehicle supply chains are complicated, a lot of specific models that are impacted by the tariffs in an intermediate way because they’re assembled in the U.S. using at least some foreign-made parts. But the same basic dichotomy applies. If heavily tariffed companies are jawboned into keeping prices flat, they will divert sales to non-tariffed jurisdictions. This will put the supply and demand curves for lightly tariffed vehicles into disequilibrium and create upward pressure on prices.

Americans, of course, typically do not buy cars from the companies that make cars.

We buy cars from car dealerships, which have these baffling, geographically fragmented quasi-monopolies. When supply and demand for Ford SUVs is placed into disequilibrium, it’s Ford dealerships, in the first instance, that will respond by raising prices. They might not even announce that prices are going up. They’ll just become less willing to bargain down or give customers good deals. Less clearance inventory will get marked down at the end of the year. But whatever happens, the end prices paid by consumers will go up. And so will dealership profits.

Maybe the foreign automakers won’t care about Trump’s jawboning.

Hyundai and Volkswagen and other companies that export lots of cars to the United States might just raise prices and accept lower sales. This also increases demand for American-made cars and makes it easier for the dealerships selling those cars to charge their customers higher prices. Importantly, while car dealership owners are, in fact, greedy—and that’s one reason they’ll raise prices—simply waving your hand and making them non-greedy doesn’t solve the problem. In that case, you end up with car shortages and people bidding up the price of used cars.

Raising Prices Is How It Works

Now consider another scenario in which Ford is not subject to jawboning.

In this scenario, instead of letting dealership owners reap windfall profits, Ford starts charging dealerships more. Dealers then raise prices and consumers pay more, but the windfall goes to Ford rather than the dealership owners.

A few things happen in this case:

The UAW has an opportunity to demand higher pay in its next contract negotiation.

Companies that are exporting cars to the United States may look at Ford’s fat margins and decide they should invest in some new plants in the United States.

Ford may look at Ford’s fat margins—and the risk of foreign companies opening new plants to compete them away—and decide that it should invest in some new plants in the United States.

If you look at what tariff fans claim the tariffs are going to accomplish, this is the kind of thing that they’re looking forward to.

But these things happen because prices are going up.

I sometimes hear from MAGA Twitter that prices won’t rise due to tariffs if companies just reshore their production. That is not correct. The tariffs raise the price of both U.S.-made and foreign-made products. The difference is that they make U.S.-made products more profitable, and that is the reason they incentivize more U.S.-based production. The goal is achieved through higher prices.

I think this is obvious, especially if you think about it in the reverse direction. The reason that (some) people are angry about the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) is that they (rightly) believe it encouraged companies to build factories in Mexico rather than in the United States. The way that worked is that a person who located his factory in Mexico could undercut a U.S.-based factory on price and thereby gain market share. And part of why the industrial unions hate this so much is that beyond the direct impact on jobs, the threat of being undercut on price by foreign producers was a way for U.S.-based employers to discipline their own workforce. I would not like it if this happened to me, either. But it’s important to acknowledge that it wasn’t just bosses being jerks—it was genuinely true that international trade let cheaper stuff into the country. Prices for durable goods fell. U.S.-based producers that refused to find ways to cut costs would genuinely have gone out of business.

The way to use trade policy to protect American manufacturing jobs is to put a floor under price competition, force Americans to spend a larger share of their income on goods and less on services, and drive new investment in American production.

I think that most people recoil from this idea when they see it spelled out, because their goal is to make the country more prosperous, and what we are describing is clearly a world in which Americans are becoming poorer. You’ll pay more for U.S.-made goods, and because you’re paying more, you’ll have less to spend on dining out, on haircuts and getting your nails done, on fitness classes, on newsletter subscriptions, on taking your kids to Sky Zone. In exchange, somewhat fewer people will work in those kinds of places and somewhat more will work in car factories. You can talk yourself into the idea that this is progressive, if you imagine that only the rich will be paying more for cars. But, in fact, waitresses and nail techs and yoga teachers and the guys who work at Sky Zone buy cars, too. In fact, lower-income people spend a higher share of their income on goods. It’s just a bad idea.

It Gets Worse

I’ve been bending over backward to talk about this as if the Trump administration is putting forward a rational policy proposal, mostly because I’m hoping that Democrats polarize out of some of their own fuzzy thinking on trade policy.

Someone like Lori Wallach, who is positioning herself as anti-anti-tariff, for example, is, I think, underrating the extent to which her ideas for creating good jobs will instead make most people worse off. Which isn’t to say that her proposals won’t work, narrowly construed—just that when people argue for creating good jobs, I think they’re hoping to make most people better off.

But as she explores in her own column, Trump’s actual decision-making is way too crazy for most of this to even be relevant. For example, while European and Korean automakers’ stock prices fell when Trump announced his tariffs, so did Ford and GM stock. The basic issue here is that essentially all automakers use complicated global supply chains to source the many components that go into modern motor vehicles. This illustration from Canada’s Automotive Parts Manufacturers’ Association shows that Canadian firms exist in a complementary relationship with their peers in the U.S. and Mexico.

The stock market’s view is that the adverse impact on supply chains is so bad that, on net, Ford and GM will be worse off, even though the tariffs should take an even larger bite out of most of their competitors. At first glance, I found that market judgment pretty surprising, since despite the hopes and dreams of urbanists, I think most people will keep buying cars no matter what Trump does. But the financial markets are usually smarter than me trying to reason from first principles. And it’s important to note that most Americans are not buying the cheapest possible car that meets their core transportation needs. If everybody’s production costs go up, a lot of consumers will need to respond by downshifting to lower-end trims or models that are usually less lucrative.

People also frequently upgrade or replace cars that are old but still functioning. If prices go up, the refresh cycle can lengthen.

Speaking of cycles, the final accursed aspect of this policy—and the reason it’s so nutty of the UAW to endorse it—is that if you’re hoping to shift investments in factories and outputs, you need to be making credible long-term commitments. There is probably some universe in which you convince people that they should move their spring and brake pad factories back from Mexico to the United States. But are these tariffs that Trump announced going to still be in place in three weeks? In three months? In three years? Does Trump actually want to erect high tariff barriers around the United States, or is he doing coercive diplomacy and aiming to extract concessions on other issues?

It’s not just that the president’s decision-making is erratic and mercurial (although it is). His team keeps offering different explanations for the goals of his trade policy. That’s not a formula for reshaping any business investment decisions; it just induces paralysis.

I saw this on the Bloomberg Terminal last week:

That’s a completely dysfunctional way for a major economy to function. Businesspeople should be thinking about new products, marketing, and improving how they make stuff, not waiting on pins and needles for the latest diktat from the central planning committee about where they’re allowed to buy aluminum from.

Read Matthew Yglesias’s second article in this series, “YIMBYism as Industrial Policy.”

A version of this article was originally published on Slow Boring. For another view on tariffs, read Michael Lind’s piece, “Why Tariffs Are Good.”