The Free Press

I did not know at my University of Texas basketball practice in 2016 (Go Longhorns!) that I was shaking hands with history. That the hand I was shaking had, in turn, shaken hands with Presidents Truman and Ford and Carter. That this hand had personally received from Martin Luther King Jr. the only copy of his “I Have a Dream” speech.

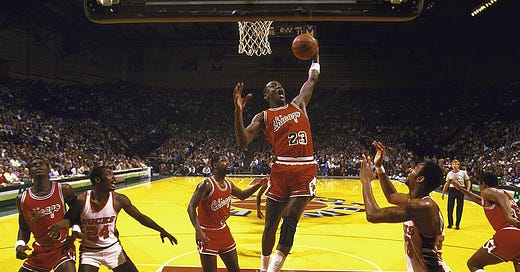

I also didn’t know that this hand had guided the legendary Michael Jordan to Nike, and helped make him a billionaire.

I thought I was just shaking hands with a friendly older gentleman named George Raveling.

I soon realized that the then–79-year-old was a towering figure, and not only because he’s six feet, six inches. His is quite a life story. When he was born in 1937, the life expectancy for a black man in the United States was 48. An orphan at 13, from segregated Washington, D.C., he earned a basketball scholarship to Villanova University. Then he paid it forward by working tirelessly to bring black talent to northern universities to play basketball, in what one 1970s newspaper described as an “Underground Railroad.” And that was just the beginning.

This man, who was illegally deprived of human rights by this country until he was 27, volunteered as an assistant coach on two Olympic teams and helped them earn multiple gold medals. This campaigner for social justice, who was handed a historical document—King’s speech—worth millions of dollars, donated it to his alma mater on the condition that it would be displayed at the Smithsonian. This coach, who used to run Jordan’s iconic basketball camps—where the legend taught normal kids how to dunk—also created the country’s first basketball camp for young women.

And this mentor, who is generous beyond belief, welcomed me into the club of those he informally guides through life.

It’s a great club to be part of. He emails us articles from his iPad. He answers the phone when we call. He brings us books. (Kobe Bryant loved to ask for reading recommendations from George.) He reminds us to put our families first. He texts just to let us know he’s thinking about us. He’s the first to congratulate us on our wins, and the first to lift us up after our losses.

So, when his son asked me last year if I thought anyone might be interested in helping his dad do a book, I said I’d ask my publisher. I’ve never seen them buy a book faster.

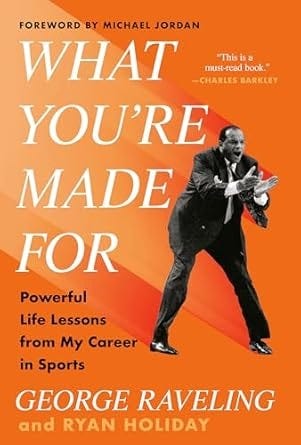

George could have written a memoir about basketball. Instead, he wanted to write a guide to life. Something that might help people.

The result, What You’re Made For, came out earlier this month, and today, The Free Press is publishing an exclusive excerpt about the secret of George’s success. He has a lot of epic stories about basketball and the civil rights movement, as well as business, from his time at Nike. You can read all of them in the book. Below is an essay that’s not about the moments of triumph in the spotlight, but the invisible work behind them. It’s a guide to winning every single day, from a man who has won a lot. —Ryan Holiday

When Michael Jordan first approached me about running his basketball camps, I was hesitant.

“Let me think about it,” I told him.

Michael looked at me, puzzled.

“What’s there to think about?” he asked.

I looked him straight in the eye, and said: “Are you going to be there every day? I’m not going to cheat the kids.”

I had my doubts about his level of commitment. And one of the reasons Michael and I got along is that I told him the truth, and he did the same with me.

“Coach, I tell you, I’m not doing this for money. If we do this, I’m going to be at the camp every day,” he said, without missing a beat.

And true to his word, over the 22 years that we ran those camps together, Michael was there every day. Plus, his focus wasn’t just on showing up for a photo op or slapping his name on the program: He was out there on the court playing pickup games with the campers, talking trash like it was an NBA game, and pushing them to compete. He gave the kids advice, shared insights, and kept in touch with everyone.

This wasn’t some celebrity cashing in on his fame: Michael was fully committed. He was sharing what made him great: his relentless drive, his focus, and his passion for the game. That’s why the camps were so successful, running for over two decades.

Michael’s attitude towards the camps was the same as his attitude towards life. For him, success wasn’t just about big moments on the court—it was about showing up, doing the work, and making those small, daily choices that add up to something great over time.

I call that attitude: winning the day.

It’s about doing the unglamorous, often monotonous tasks that are necessary if you want to be better tomorrow than you are today.

When people talk about greatness in sports, they often focus on singular, heroic moments. For example, Michael’s famous “flu game.”

It was June 11, 1997, Game 5 of the NBA Finals, between the Chicago Bulls and Utah Jazz. The series was tied 2-2. Michael had been up all night, violently ill. He missed breakfast with his teammates. Around 8 a.m., the Bulls trainer, Chip Schaefer, found him curled up in the fetal position, wrapped in blankets, with the thermostat cranked as high as it would go. Jordan was in no condition to join the pregame shootaround.

Was it food poisoning? Altitude sickness? The flu? No one knew for sure, but everyone who saw him thought the same thing: There’s no way he’s playing in Game 5. But when Jordan’s mother, Deloris, suggested he sit this one out, he replied: “Mom, I have to play.”

What followed was the stuff of legend. Despite being visibly weakened, often doubled over on the court gasping for breath, Jordan led a comeback from a 16-point deficit in the first quarter. He won the team 38 points, including 15 in the fourth quarter, securing a crucial win for the Bulls.

But when people recount this story, they often miss the point. They talk about how Jordan tapped into something that the sports world still struggles to put into words. They focus on what he did that night, willing himself to greatness in those 48 minutes.

But of course, the real key wasn’t what happened on June 11, 1997. It was everything that came before—those moments of discipline, dedication, and drive that were unseen and uncelebrated. It was the countless hours spent honing his skills in the gym, the rigorous training that pushed him to his limits day after day. It was the meticulous study of game film, the precision with which he managed his diet and recovery, and the relentless pursuit of improvement in every facet of his game.

That night was the culmination of years spent winning the day, over and over again.

This is what I always tried to impress upon the players I coached. Greatness isn’t about rising to one extraordinary occasion—it’s the product of countless ordinary ones. It’s not the dramatic moments that define you, but the habits you’ve built when no one is watching. It’s the quiet but relentless effort to win every day that ultimately leads to greatness, when the spotlight finally shines.

Kobe Bryant echoed this idea in The Mamba Mentality, writing:

“You have to work hard in the dark to shine in the light. Meaning: It takes a lot of work to be successful, and people will celebrate that success, will celebrate that flash and hype. Behind that hype, though, is dedication, focus, and seriousness—all of which outsiders will never see.”

That relentless commitment to excellence is what separates the good from the great, the successful from the truly iconic. As Michael put it, “I just think that I had the ability to work hard every day, long after most people stopped showing up.”

Most people can’t do it. One of my best friends, the college basketball coach Buzz Williams, has a saying that perfectly encapsulates this philosophy: “The best thing we do is every day, and the hardest thing we do is every day.” According to Buzz, it’s practice that “proves who’s an Every Day Guy. And if you’re not an Every Day Guy, it doesn’t mean we love you less, it just means you’re going to have to sit over there on the side.”

Of course, even the Every Day Guys struggle. The paradox is that the more you do something, the better and better you become at it, but the repetitive nature can make it harder and harder to keep doing it. Michael once told me: “Each time you win, it takes away a little of that hunger. The challenge is finding that same place in your mind—five, six, seven, eight times. That’s hard.”

He added:

“When people say winning the first championship is the hardest, I tell them, ‘No, the next one is.’ Because you’re battling yourself, the monotony of doing the same things over and over. Most days, the battle is just with myself. Can I keep challenging myself? That’s the hardest part.”

This lesson isn’t about basketball. It’s about life. Part of winning the day is pushing yourself to improve and evolve, even when you’ve reached the mountaintop.

For me, winning the day starts with a simple but powerful choice every morning. As I put my feet on the floor, I say to myself, Okay, George, you have two options today, and only two. You can be happy, or you can be very happy.

It’s a reminder to myself that I have the power to set the tone for my day.

Then, I come up with a strategy for winning the day.

I ask myself: What can I do today to be better than I was yesterday? What small victory can I achieve in the next hour, the next minute?

Right now, why not ask yourself: How can I make the most of this moment right in front of me?

The Free Press earns a commission from any purchases made through all book links in this article

Want to keep thinking about how to win every day? Last year, Kelli Finglass, director of the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders, appeared on “Honestly”—and explained how she built one of the most competitive teams in America. You can listen to it here.