In the 1940s, there were around 20,000 Jews still living in Lebanon. Just 20 years later, in the span of one generation, that number dropped to around 3,000. Gad Saad is among those statistics—born in Lebanon in 1964 into one of the last Jewish families to remain in the country.

But the nation that was once called the Paris of the Middle East began to turn when he was a child. He remembers being at school one day when a fellow student told the class he wanted to be a Jew killer when he grew up. The rest of the kids laughed. By 1975, Lebanon had descended into a brutal civil war, and Gad remembers death awaiting him every millisecond of the day. He spent his childhood years mindful of which streets had snipers when he went outside to play. But even then his family thought, This will pass. That is until someone showed up at their home to kill them—at which point the Saad family fled to rebuild their life in Canada. Gad went on to become a professor of marketing and evolutionary behavioral sciences at Concordia University in Montreal.

Many of us in Western democracies find ourselves saying the exact same things: This will pass over, everything will be fine. We say that even as Hamas flags and “I love Hezbollah” posters fly in cosmopolitan capitals across the West. I’ve been asking myself a lot over the past year: How worried should we be? Am I being hysterical? And is there a way to roll back this anti-civilizational impulse that has been let loose?

Those are just some of the questions I put to Gad Saad in our conversation. Gad says that witnessing the Lebanese Civil War gave him a crash course in the extremes of identity politics, tribalism, and illiberalism. And he says that immigrants like himself, who have lived without the virtues of the West—virtues like freedom of speech and thought, reason and liberalism—uniquely understand what’s at stake now in Western cultural and political life.

If you’re on X, I suspect you know Gad’s name. Unlike most professors, he has a million followers and a knack for satire, so much so that Elon Musk seems to be one of his biggest fans. He has become one of the most insightful and provocative thinkers on the risks of mob rule and extremism on the left.

Meanwhile, he is now having second thoughts about the university where he has worked for the past 30 years. That’s because Concordia is now widely regarded as one of the most antisemitic universities in North America. As a result, Gad is currently a visiting professor and global ambassador at Northwood University in Michigan, and he says he can’t face returning to Concordia and maybe even Canada, given the antisemitism that’s run rampant there. All of this, he argues, constitutes another war, different but related to the one he witnessed in Lebanon as a child. This one is a war on logic, science, common sense, and reality, here in the West.

These are ideas he explains in his important book, The Parasitic Mind: How Infectious Ideas Are Killing Common Sense. In our wide-ranging conversation, I asked Gad where these parasitic ideas came from and why they’re encouraged in the West. And importantly, I ask if these trends are reversible.

To listen to the podcast, click below, or scroll down for an edited transcript of our conversation.

On the ever-present threat of violence in Lebanon and his family’s decision to flee:

Bari Weiss: I wonder if you could take us back in time to the 1960s, to Lebanon before the war. You’re one of the last of a very small Jewish community living there. Take us back to the world you were born into.

Gad Saad: So I was born in 1964. We were steadfastly, doggedly refusing to leave Lebanon, despite the fact that, yes, you’re right, that there was a time when Lebanon was considered progressive, certainly by Middle Eastern standards. But much of my extended family had read the writing on the wall and had left earlier, prior to the civil war, many of whom left for Israel. And one maternal aunt left for Montreal. That’s one of the reasons why we ended up immigrating to Canada. Bit by bit, each of my siblings had left Lebanon, but I remained because I was a young kid.

And so, just to give your audience a feel of what it was like growing up Jewish in Lebanon: When I was a child, I was in a class where the teacher asked us to get up and tell what we’d like to be when we grew up. And so you get the typical professions. “I’d like to be a doctor. I’d like to be a police officer. I’d like to be a soccer player.” And one kid, who is a kid that knew that I was Jewish, got up and said, “When I grow up, I want to be a Jew killer,” to raucous applause and laughter. And that’s just the typical thing that you would see in the Middle East.

BW: You’re 10 or 11 years old, the war breaks out, and, of course, your family is forced to flee. Was there a particular moment that you remember? Knowing that we were going to have to get out of here to save our lives?

GS: There are many, many such moments, because death awaited you at every millisecond of the day. For example, my parents would tell me, “You can go out and play outside, but don’t pass this particular line, because that would open you up to the eyesight of the snipers that are on this building.” And I’m actually getting goosebumps saying this.

Why Lebanon’s identity politics should be a warning to America:

BW: For the listener who is only paying attention to Lebanon now because it’s in the news, can you briefly explain to us the nature of the civil war so that people don’t have to go running to Wikipedia, which is now overtaken by propagandists?

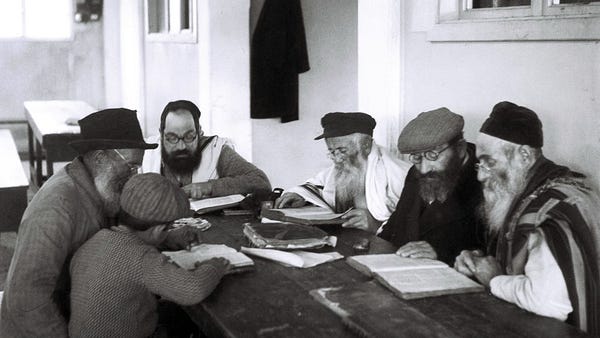

GS: So the Lebanese Civil War was from 1975 to 1990, officially. And during that time there are different estimates. But the most common estimate that I’ve seen is that roughly 150,000 people were killed. Now, in a country of, say, 3 million people, that gives you a sense that it’s pretty sizable. Now, different people will argue that, no, it was a political war. It wasn’t. The reality is that it had a clear religious timbre to it. There were several Christian militias that were fighting several Muslim militias. Now, the Muslim militias, when they’re not fighting against the Christians, could turn the guns against each other and fight one another. So it was complete chaos. The reality is that everything in Lebanon is viewed through the prism of religion. Who could be prime minister or who could be president? How many seats you get in the parliament is all based on your religion.

BW: I want you to explain the connection between the ideology that you began to encounter in the mid-1970s in Lebanon and the identity politics that has subsumed so much of our culture here in the West.

GS: Well, Lebanon is the perfect exemplar of what happens when identity politics are taken to their nefarious limits. Everything is viewed through the lens of which religion you belong to. So it really is identity politics on steroids. And so I see certain political movements, whether it be in the United States or in Canada or in the West in general, that are very much wedded to that idea. One of the parasitic ideas that I speak about in the book is precisely linked, as you said, to identity politics. And I tell people, hey, watch out, because if you want that perfect example of what identity politics is in terms of how you organize society, Lebanon is the place. Syria is the place. Iraq is the place. Rwanda is the place. So it’s never a good idea when people who live under a supposedly unified nation are more tied to whatever identity marker first defines them more so than the country. What made the United States great is that I could be anything, but nothing was superseded by my commitment to American values. Once you erase that, once you eradicate that foundational value, you’re going to run into problems. It might take 100 years, it might take 500 years, but you will get the exact same final outcome.