The Free Press

“I don’t know if Venezuela will be fixed, but I always wanted a yacht. With three master’s degrees and a PhD, I can barely afford a car, and that will be fixed.” I heard those words from the chief strategist for the first Hugo Chávez presidential campaign in 1998.

At the time, he was my journalism school professor. He told me this the day before Chávez won. Two years later, he bought that yacht.

According to Venezuelan law, Chávez’s presidency should have ended peacefully in 2003. Instead, he changed the constitution, took control of every aspect of civil and military life in the nation, and ushered in a socialist revolution that has immiserated my home country.

That public university where I got my degree went from being one of the top in Latin America to losing most of its professors because it couldn’t pay them a living wage. As for me, I made a movie called Secuestro Express in 2006, which angered the government so much they charged me with “portraying the authorities in a negative light.” The punishment, I discovered, would be six to ten years in prison. Two hours after I heard of the charges, I moved to the United States.

I have never stopped fighting for freedom in my homeland. But to be honest, like many of the nearly eight million people—a full third of the country—who have left Venezuela over the past decade, it was hard not to give in to total despair when I looked at the reality back home.

From 2012 to 2022, inflation has skyrocketed by 9,033 percent. The minimum wage in Venezuela is three dollars a month. Children are starving to death. Eight out of every ten Venezuelans live in poverty, despite the nation having the largest proven oil reserves in the world.

How would Venezuela ever recover from the man-made hell that Chávez, and his successor, Nicolás Maduro, have created?

Hope came for me, and for the people of Venezuela, in the form of a slight 56-year-old woman named María Corina Machado. She is known as the Iron Lady. And right now—in the wake of Sunday’s contested election—she and the opposition movement she has created are the only things standing between the people and Nicolás Maduro and his thugs.

María Corina is not an obvious subversive. She comes from a traditional, upper-class family. Perhaps that’s why Maduro and his people underestimated her. They considered her too white and too rich—she went to Yale—to win the majority’s support.

And until last year, they were right.

Past opposition leaders have disappointed the people, either giving up or giving in. But for decades, María Corina has been unwavering in her determination. Venezuelans no longer care if she comes from a rich family or how white she is. She talks about free enterprise. She talks about the individual, the dignity of starting one’s own business, and keeping the government away from the ability to live one’s own life. She talks about reuniting families in a nation torn apart by mass migration, where grandparents die alone because their children decided to walk thousands of miles and cross jungles to reach societies where they can thrive.

Finally, Venezuelans began to see her as our only hope.

These days, everywhere she goes, children rush to see her and grown men are moved to tears. When the regime cuts the electricity in a town where she is about to give a rally, the people turn on the flashlights on their cell phones and silence themselves to listen. When the regime blocks the roads, the fishermen bring her in by boat.

In October 2023, she ran in the opposition primaries for the presidential election—and won an overwhelming 93 percent of the vote.

She won because her slogan is hasta el final, which translates to “until the end.” That promise means she knows the regime is capable of anything to stay in power, and unlike the opposition leaders that came before her, she will keep on fighting. Her allies have been arrested. Hotels and businesses supporting her have been shut down by the regime. And hundreds of political prisoners, every day, face the threat of rape and torture for standing up as she now does. And yet, María Corina has not backed down.

As long as she remains resolute, the people will follow her, no matter the cost. Even though the regime blocks TV channels from broadcasting her image, and radio stations from transmitting her voice, social media powers her campaign.

For all of these reasons, Maduro is terrified of María Corina. His regime has blocked her candidacy at every turn, going so far as to disqualify her from Sunday’s presidential race on the risible charges of corruption and supporting U.S. sanctions against Venezuela.

But she found a way. She coordinated with Edmundo González Urrutia, a low-profile former diplomat, who registered to oppose Maduro without much notice. María Corina urged Venezuelans to support González Urrutia under the Plataforma Unitaria Democrática—a coalition of ten opposition parties. This is why, even though everything you are seeing in the news about Venezuela is happening thanks to María Corina, the person on the ballot is González Urrutia, a decent man who acts as her representative.

On Sunday, more than nine million Venezuelans turned out to vote, a record number especially considering those citizens outside the nation who were not allowed to take part. Exit polls by several independent polling companies point to a landslide victory for Gonzáles Urrutia, with 70 percent of the vote—an amount consistent with months of pre-election polls. María Corina’s candidate appears to have beaten the revolution, even though the revolution won’t admit it yet.

The next hours and days will be the ultimate test of hasta el final—and every moment brings a new development. On Monday, the regime announced that she will face prosecution for electoral interference and a number of other crimes. And members of María Corina’s team, who have been holed up in the Argentina embassy for months, were surrounded by government paramilitary thugs until she denounced it on social media and her supporters came out to repel them.

Meantime, ordinary Venezuelans have taken to the streets. They are tearing down statues of Chávez and Maduro in tiny, rural towns like Calabozo and in large cities across the country. They are ripping Maduro’s face from billboards. They are thronging military bases, begging the army to certify her victory. Gangs on motorcycles are riding through residential neighborhoods to intimidate her opposition, and the National Guard has already started repressing the demonstrations. There are no official casualty numbers yet, but disturbing images have started appearing on social media.

And still, María Corina refuses to back down. On Monday evening she announced she has 73 percent of the voting records, and that there are 6,275,182 votes for Edmundo and 2,759,256 for Maduro. She called on the people to show up on Tuesday in front of the local office for the United Nations, to start the process of proving to the world that “we won.”

There are two vote counts in Venezuela: a digital total is sent by voting sites to the country’s election body led by a Maduro ally, and a tally of physical ballots, which is printed by every election machine. The night before the election, thousands of María Corina’s supporters slept outside their polling stations to ensure they would catch any irregularities. It turns out they were right to be worried. When a voting center in the rural state of Portuguesa opened, one computer had already tallied 3,000 votes for Nicolás Maduro. The people caught it and police had to escort out the woman in charge to protect her from the furious crowd.

There were shameful scenes like this across the country. In San Cristóbal and El Valle, military men stole the paper tallies, leading to violence across the country. In one state, Táchira, at least one man was killed as authorities stormed the voting center. He lost his life trying to protect the votes.

But the evening was also filled with joy, as each voting center read out the results to the waiting crowds. Each scene was more overwhelming than the last. Even in Caracas, in the school where Hugo Chávez used to vote, Maduro lost. Exit polls showed the opposition winning by at least 70 percent. There was a sense of euphoria, as a 25-year-long dictatorship seemed to be ending, and the nation that created the best telenovelas was hoping the villain would do the right thing in the end.

But at midnight, the fraud came.

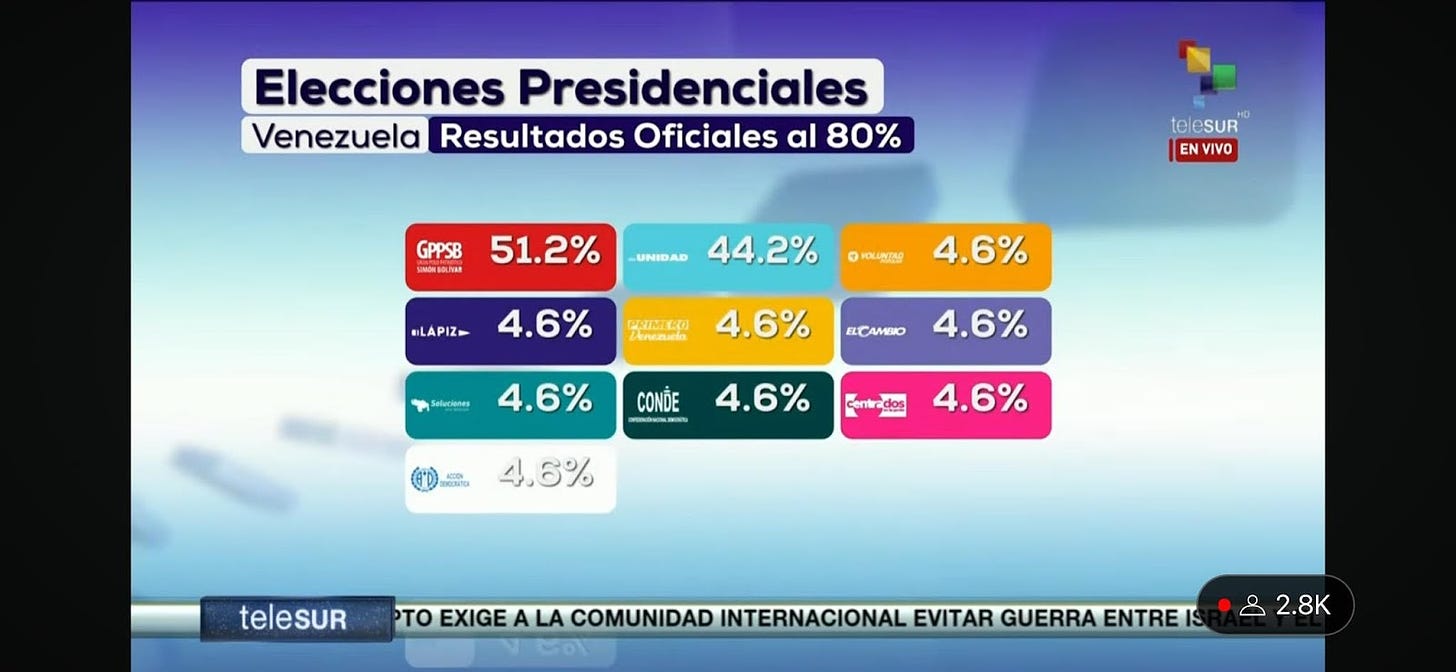

And it was laughable. The total vote count announced by the Electoral Council, CNE, added up to 132.2 percent, and eight parties received the same exact percentage: 4.6 percent. Maduro, they claimed, had won 51.2 percent of the vote. There was not even an attempt to make it look realistic. Finally, on Sunday night, Maduro claimed the electoral system was hacked and stopped the count. Carlos C., a radio host who spent two years as a political prisoner and asked to speak anonymously, told me last night, “They allow the numbers to be evidently fake because that’s how they show their power. They are laughing at us. And they want to make sure we know they are laughing at us.”

An hour after Maduro shut down the election, María Corina asked witnesses at polling stations to stay put and collect all the votes. She is not calling for violence, which is a big deal given how many lives we’ve lost fighting in the streets against a rootless military. She says she hopes the army will honor the results but is not waiting for them, and she has called on every Venezuelan to defend their sovereignty and do their part to prove there was a landslide.

“For the first time, there’s unity,” Julio Jiménez Gédler, a Venezuelan political analyst, told me yesterday after the vote. “And I’m not talking about unity between those who always opposed the Chavistas. I’m talking about a significant part of the Chavistas, who have been loyal for two decades, voting against Maduro. This was a knockout. The social base of this movement is unlike anything we’ve seen before.”

Perhaps many Americans don’t think much about Venezuela. They should—and not just because inflation and immigration are currently among the most prominent issues in U.S. politics. What happens in Venezuela over the following few days will significantly affect both. If Maduro stays in power, at least four million more people are expected to leave the nation in the next year or two, furthering a refugee crisis that has impacted every single country in the Americas, including the United States. If nothing else, with Maduro, your gas will remain expensive.

The bigger reason to care is that the siren song of socialism is seducing many in the West right now. Venezuela is the single most powerful case study in the foolishness of that path—and the heroism required to get out of it.

My former university professor spent Sunday afternoon tweeting about the stages of grief. Even he, who had enriched himself off the Chávez regime, suggested that Maduro and those around him needed time to accept defeat.

“The first stage of grief is negation,” he wrote. “Their first reaction will be to deny their defeat. It’s important to give them space so they arrive at reason. Patience and emotional intelligence is needed. They are about to lose their power and privilege, and it’s important to build bridges toward them to ease that path.”

He could be right. On Monday evening, we started to see images of police officers removing their uniforms as they refused to repress their people. And while there are reports of the National Guard taking a more violent approach, in the end, the soldiers and the police corps are also experiencing the horror of life without freedom. It is no longer the upper and middle classes protesting the revolution. It is now the poor, the same folks who once thought socialism was going to lift them out of poverty, the ones who said “enough.” They are the brothers and sisters of the officers who are being told to stifle their dreams.

Venezuela is slowly uniting. The hope for a future reconstruction is growing every minute, as is the feeling that freedom-loving Venezuelans won’t give up hasta el final.

Jonathan Jakubowicz is a Venezuelan writer/director living in Los Angeles. You can follow him on X @JoJakubowicz or on Instagram @expressjj.

And read Francis Foster’s piece about Venezuela, “Black Humor in ‘Communist Fat Camp.’ ”

To support our mission of independent journalism, become a Free Press subscriber today:

It seems that the army and National police are the ones who hold the power. How long can those generals stand by while the country is being brought to ruin by a few greedy S.O.B.s?

Thanks, Jonathan. THIS is the kind of story I subscribed for.